Estudios e investigaciones / Research and Case Studies

Generative artificial intelligence for self-learning in higher education: Design and validation of an example machine

Inteligencia artificial generativa para autoaprendizaje en educación superior: Diseño y validación de una máquina de ejemplos

Generative artificial intelligence for self-learning in higher education: Design and validation of an example machine

RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, vol. 28, núm. 1, 2025

Asociación Iberoamericana de Educación Superior a Distancia

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional.

How to cite: Sánchez-Prieto, J. C., Izquierdo-Álvarez, V., Del Moral-Marcos, M. T., & Martínez-Abad, F. (2025). Generative artificial intelligence for self-learning in higher education: Design and

validation of an example machine. [Inteligencia artificial generativa para autoaprendizaje en educación superior: Diseño y validación de una máquina de ejemplos].

RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.28.1.41548

Abstract: Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI), as an emerging and disruptive technology, has revolutionised human–machine communication. This new means of interacting with electronic devices has opened up interesting possibilities in the educational field. The objective of this study was to analyse the effectiveness of interactive and practical example-generating machines developed by generative AI for the study and review of content in university education. Using an evaluative research approach, a process of design, validation, and pilot implementation of four prompts developed by the ChatGPT tool was implemented. After designing each prompt, its functionality was validated by three expert judges who applied a systematic testing process. The final prompts were piloted on a sample of 192 students with education sciences degrees, who evaluated the usefulness and their overall satisfaction with the example-generating machines based on scales validated in previous studies. The testing results revealed better performance of the example-generating machines with simpler prompts. Moreover, the students indicated very high satisfaction with the machines along with a high perception of their usefulness. Specifically, while women showed higher perceptions of usefulness than men in a few of the measured indicators, the perceived usefulness was generally higher in the groups of students in which the machine committed errors during the pilot. Despite the limitations of the tool, the results obtained are promising.

Keywords: generative artificial intelligence, example machine, ChatGPT, self-learning, research methodology, higher education.

Resumen: La Inteligencia Artificial (IA) generativa, como tecnología emergente y disruptiva, ha supuesto una revolución en la comunicación hombre-máquina. Esta nueva forma de interactuar con los dispositivos electrónicos abre interesantes posibilidades en el ámbito educativo. El objetivo de este trabajo fue analizar la eficacia de una máquina de ejemplos prácticos interactivos desarrollada con IA generativa para el estudio y repaso de contenidos en enseñanzas universitarias. Bajo un enfoque de investigación evaluativa, se llevó a cabo un proceso de diseño, validación e implementación piloto de cuatro prompts desarrollados en la herramienta ChatGPT. Tras el diseño de cada prompt, se validó su funcionamiento por parte de tres jueces expertos, que aplicaron un proceso de testeo sistemático. Los prompts definitivos fueron pilotados en una muestra de n=192 estudiantes de titulaciones de Ciencias de la Educación, que valoraron la utilidad y su satisfacción general con las máquinas de ejemplos a partir de escalas validadas en estudios previos. Los resultados del testeo mostraron un mejor desempeño de las máquinas de ejemplos con prompts más sencillos. Por otra parte, los estudiantes mostraron una satisfacción muy elevada con las máquinas, junto a una elevada percepción sobre su utilidad. Específicamente, mientras que las mujeres mostraron percepciones de utilidad más elevadas que los hombres en alguno de los indicadores medidos, la utilidad percibida fue más elevada en general en los grupos de estudiantes en los que la máquina cometió errores durante el pilotaje. A pesar de las limitaciones de la herramienta, los resultados obtenidos resultan prometedores.

Palabras clave: inteligencia artificial generativa, máquina de ejemplos, ChatGPT, autoaprendizaje, metodología de investigación, educación superior.

INTRODUCTION

Artificial Intelligence (AI) originated around the year 1956 in the United States, when discussions on intelligent systems began (Hirsch-Kreinsen, 2023; Sánchez, 2024). In the following years, progress was made in its use across various fields, such as neural networks, for processing large amounts of data (González & Silveira, 2022; Hirsch-Kreinsen, 2023). However, the significant impact of generative AI occurred with the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 (Sánchez, 2024), a chatbot created by OpenAI that is capable of generating coherent and informative human-like responses (Eysenbach, 2023; Lo, 2023).

For Mintz et al. (2023), the change was not a revolution in itself but in the fact that anyone could access this technology. Although AI was already present in daily life through smartwatches, chatbots, shopping recommendations, or music playlists (Kennedy et al., 2023), the emergence of generative AI has transformed multiple aspects of social life, creating new realities in culture, science, communication, and, of course, education (Kennedy et al., 2023; Martinez et al., 2019; Pavlik, 2023).

Surden (2019) defines AI as the technology that enables ‘automating tasks that typically require human intelligence’ (p. 1307). In this sense, the purpose of generative AI is to enable computers to learn to reason and interpret like humans through prior experiences (Copeland, 2023; Rebelo et al., 2022). These technologies are designed to enable personalised learning, automate trivial administrative tasks, or provide real-time feedback (Chaudhry & Kazim, 2022; Guan et al., 2020; UNESCO, 2021).

With the advent of generative AI, the creation, application, and research on these tools have expanded into various scientific fields, such as healthcare (Cascella et al., 2023; Choi et al., 2023), business (Deike, 2024), and education (Cooper, 2023; Saif et al., 2024).

In education, generative AI presents significant potential for innovation and improvement. In fact, UNESCO (2021) highlights the opportunities that generative AI offers for addressing educational challenges through innovation in teaching–learning processes. Hsu and Ching (2023) add that its scope is almost limitless due to the use of natural language by users. Although AI technologies were already being used in teaching–learning processes—such as adaptive learning, intelligent tutoring systems, or big data (Mao et al., 2024)—generative AI adds considerable value when quick responses to specific tasks are required, such as providing text, images, or music (Mao et al., 2024).

Despite the undeniable potential of these new tools in the educational sector, academic institutions are reacting in different ways, either encouraging their use or prohibiting it (Ahmad et al., 2023). Lo’s (2023) study highlights that tools like ChatGPT have the potential to assist teachers as virtual tutors for students (e.g., answering questions) or as assistants (e.g., generating teaching materials and offering suggestions). However, their application poses certain challenges, such as generating incorrect or false information in interactions or evading plagiarism detectors. It also raises concerns related to legal and ethical aspects, safety, transparency in AI decision-making processes, and even issues in students’ intellectual development (Kalota, 2024). With regard to this last aspect, there is concern that excessive use or dependence on AI could lead to problems in problem-solving abilities and critical thinking (Alam et al., 2023; Stokel-Walker & Nordeen, 2023).

While generative AI may offer significant benefits in innovation and make contributions to the digital society, other concerns exist, such as the possible increase in techno-educational gaps that may exacerbate inequalities (González & Silveira, 2022) or the development of unethical practices in academic writing and assessments (Sánchez, 2024). Mintz et al. (2023) indicate other significant challenges, such as user privacy, the role of teachers and pedagogy, plagiarism, commercial exploitation of collected data, response biases, or increasing social inequalities. In fact, generative AI-based tools like ChatGPT have significant limitations in supporting academic activities, such as the inability to provide accurate bibliographic references or the tendency to suggest non-existent sources (Karakose, 2023).

Despite these limitations, Mao et al. (2024) warn of the impact that generative AI tools could have on education, noting that they will likely primarily affect teaching–learning processes, teacher–student interaction, and assessment processes. In this vein, Hsu and Ching (2023) highlight various potentialities of such tools: for teachers, they note that tools like ChatGPT can support teaching through suggestions, enhance teaching quality, improve communication with different educational agents, or support assessment processes; for students, new opportunities could arise for creating personalised learning environments, spaces to foster creativity, reading and writing, or assessment. With regard to assessment, the effective use of generative AI can promote self-assessment, enabling students to critically evaluate technology, encouraging self-reflection and self-regulation (Mouta et al., 2023), and fostering students’ motivation for learning (Ali et al., 2023). Kuhail et al. (2023) indicate that the use of generative AI promotes optimised and effective learning. Indeed, the use of these tools is considered a means to engage students in their learning processes through content personalisation, thus preparing them to face the challenges of the twenty-first century ( Ruiz-Rojas et al., 2023).

Further, the use of generative AI tools for knowledge acquisition implies the possibility of creating personalised and adaptive learning environments with immediate feedback for students based on their performance levels (Mao et al., 2024). A few empirical studies demonstrate the pedagogical possibilities of generative AI, enabling personalisation, practice, or the generation of new content (Sánchez, 2024). Along these lines, Ayuso-del Puerto and Gutiérrez-Esteban (2022) conducted experiences with generative AI for initial teacher training and found improvements in students’ self-learning, motivation, and problem-solving skills, thereby achieving meaningful learning experiences. In their study with teachers from various educational levels, Bower et al. (2024) evaluated the impact of generative AI on teaching and assessment, finding that most teachers identified generative AI as having a significant impact on both aspects. Thus, Bower et al.’s (2024) results revealed the importance of first teaching students how to use generative AI, showing them how it works, or warning about the importance of critical thinking and ethical skills. Jauhiainen and Guerra (2023) used ChatGPT to generate and modify content with primary education students. The students benefited from the personalisation of materials based on their skills and knowledge, although a few issues were identified with the tool, thereby suggesting the need for future refinement to ensure its utility in education. Certain studies on the use of ChatGPT by university students reveal gender differences in attitudes, perceived usefulness, and ease of use, favouring men in certain cases ( Stöhr et al., 2024; Yilmaz et al., 2023) and women in others (Raman et al., 2024).

Another factor that influences the integration of generative AI tools in education is the distrust they generate, not only due to ethical issues (Petricini, 2024) or their potential effect on societal development (Brailas, 2024) but also due to the unreliability of their responses and their tendency to use abductive reasoning that generates false information that individuals may not recognise (Illera, 2024). This risk increases when the individual has little knowledge regarding the subject, raising the question of the effect that the awareness of the fallibility of generative AI may have on students’ use of this technology.

In summary, it appears necessary for teachers at all levels to acquire competencies in the use of generative AI tools (Karakose et al., 2023), being able to integrate them into their teaching strategies, improving teaching–learning processes, and developing students’ competencies in the use of these tools (Bower et al., 2024; Mouta et al., 2023). Therefore, this study aims to advance the use of generative AI to create educational content for students, a line opened in previous research that employed this tool for generating questions on a specific topic ( Ling & Afzaal, 2024), creating mentor texts (Nash et al., 2023), or as a practical example-generating machine for developing analytical skills (Mah & Levine, 2023; Trust & Maloy, 2023). This research focuses on the latter application, with the objective of analysing the effectiveness of generative AI as a tool for generating items or practical examples that facilitate autonomous study and review by students. Thus, it includes the designing of prompts, their content validation, and a pilot experience.

METHOD

This study utilised an evaluative research design that analyses the use of ChatGPT as an example-generating machine to support autonomous learning. The following research questions were formulated in this regard:

RQ1. How do students evaluate the potential of ChatGPT as an example-generating machine for studying and autonomous learning?

RQ2. Does gender influence students’ attitudes towards the example-generating machine?

RQ3. Do errors in the functioning of the example-generating machine affect students’ evaluation of the tool’s educational potential?

Tool design

Four faculty members responsible for the educational research methodology course across four degree programmes (primary education, early childhood education, pedagogy, and social education) at the Faculty of Education, University of Salamanca, collaboratively designed the set of instructions for ChatGPT (hereafter referred to as ‘prompt’).

This team determined the content to be addressed by the example-generating machine, adhering to the following criteria: (1) the content pertains to research designs in education, (2) the content has a clear and discernible typology through a straightforward logical process, and (3) the content is taught similarly across the four degree programmes. These agreements aimed to ensure uniformity in the prompt design across the four degree programmes, although there were a few exceptions that are discussed later.

The following course content was included in the prompts: (1) types of research designs according to their experimental or non-experimental nature; (2) types of variables according to their role in the research design; and (3) types of sampling according to its probabilistic or non-probabilistic nature.

The cooperative prompt design process was based on the guidelines established by Korzynski et al. (2023) and Reynolds and McDonell (2021). Each prompt was structured into the following three sections:

- Context: An introductory paragraph to inform ChatGPT of the purpose of the subsequent text sections.

- Knowledge Base: Text introduced between triple tildes, providing an explanation of the course content for which examples are sought. In this manner, students do not need to provide their own definitions to ChatGPT nor will the tool rely on its own database; instead, examples will be generated based on a series of definitions created and validated by the course instructors.

- Instructions: An explanatory text detailing the tasks ChatGPT should perform based on the knowledge base. Initially, the machine generates an example of research that includes the discussed content. From the example, students must attempt to guess the research design, variables, or sampling method presented. If the student provides the correct answer, ChatGPT provides positive feedback; if incorrect, it returns an additional hint and allows another attempt. Once the example is guessed, the student can choose to request more examples or end the conversation.

To facilitate free use of the machine, ChatGPT version 3.5 was employed for the prompt design and training. Initially, an attempt was made to unify the three content areas into a single prompt to produce more complex examples. However, it was observed that ChatGPT struggled with logical operations and identifying correct responses in its examples; this led to the decision to separate the content into simpler, independent prompts. This approach simplified the knowledge bases and reduced the logical complexity of the tasks requested. Ultimately, four prompts were designed to address the course content related to the competency in identifying and classifying the basic elements of research (Table 1).

|

Name of the prompt |

Content |

|

Variables in experimental designs |

● Dependent and independent variables |

|

Variables in non-experimental designs |

● Criterion and explanatory variables |

| Research designs |

● Experimental designs: --- Pretest-posttest with control group --- Posttest only with control group --- Single group ● Pre-experimental designs: --- Cross-sectional --- Longitudinal |

| Sampling |

● Probabilistic --- Simple random --- Stratified --- Cluster ● Non-probabilistic --- Convenience --- Snowball --- Criterion-based --- Quota |

Content validation

Once the four prompts were designed and internally tested by the design team, expert judges implemented a content validation process.

Three researchers in the field of Educational Research Methods were contacted to test the four prompts. They provided a report that identified errors in the examples and subsequent responses following these instructions: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1DGuSxkFwT5T0-j7pGcYOguoTKC6Gu3GY/view?usp=drive_link

Each judge conducted 10 tests for each prompt—five that provided the correct answer to the example received and five that provided an incorrect answer. Thus, each expert judge tested 40 examples from the machine, with a total of 120 test examples across the three judges. Each attempt was conducted by opening a new conversation in ChatGPT and reintroducing the three sections of the prompt. The test results were recorded in a spreadsheet with the following sections:

- Name: Name of the prompt.

- Number: Test number.

- Modality: Attempt with a correct or incorrect response.

- Example: Text of the example provided by ChatGPT.

- Example Evaluation: Adequacy of the example provided by ChatGPT (correct/incorrect).

- Response: Text of the judge’s response to ChatGPT.

- Feedback: Text of ChatGPT’s feedback as a reaction to the judge's response.

- Feedback Evaluation: Adequacy of the feedback provided by the program.

- Observations: Space for qualitative comments.

After receiving the evaluations from the three judges, corrections were made to finalise the prompts. A document containing the code for the four prompts was then made available to students on the virtual campus for their use: (https://drive.google.com/file/d/1sXg0iR7Qzkmp6NIuYLJCS428E0qFInYq/view?usp=sharing).

Pilot test

For the empirical validation of the prompts, a pilot test was conducted with students from each degree programme in March 2024. During a course session, the operation of the example-generating machines was explained. These sessions, which lasted approximately 30 minutes, included (1) a brief introduction that clarified basic aspects of ChatGPT’s functioning and the purpose of the designed example-generating machines; (2) a presentation and test of each prompt, explaining its structure (context, knowledge base, and instructions) and guiding students as they tested them on ChatGPT on their own devices; and (3) free practice allowing students to independently try out the prompts on their computers. In all cases, the faculty demonstrated the operation by generating at least two test examples, which students replicated in parallel on their computers, resolving any issues that arose during the process.

This pilot test served a dual purpose: (1) to verify the functionality of the example-generating machines on a large number of computers and the students’ ability to detect any errors that might occur and (2) to collect information on the students’ evaluations.

To collect this information, an instrument with two sections was applied. The first section collected participant identification data: gender (male, female, other), degree (Early Childhood Education, Primary Education, Social Education, or Pedagogy), and age. The second section included two scales validated in previous studies for evaluating innovations (Martínez-Abad and Hernández-Ramos, 2017; Olmos et al., 2014): the usefulness of AI and overall satisfaction with the tool. The scale content was adapted to explicitly reference AI. Twelve items (Table 2) with a Likert-type response scale ranging from 0 to 10 points (0 = strongly disagree, 10 = strongly agree) were applied.

| Dimension | Item | Text |

| Usefulness | The use of AI will help me… | |

| U01 | in the memorization and reproduction of content about research methodology | |

| U02 | in understanding the basic concepts and ideas about methodology | |

| U03 | in generalizing theoretical knowledge to real situations | |

| U04 | in solving practical problems | |

| The use of AI... | ||

| U05 | will enhance my learning in the subject | |

| U06 | will help me improve my academic results in the subject | |

| U07 | will adapt to my learning pace | |

| U08 | will adapt to my specific needs during the teaching-learning process | |

| U09 | will help increase my interest in the subject's content | |

| Overall Satisfaction | Overall… | |

| S01 | if I were to take the course again, I would like to have this resource | |

| S02 | despite its limitations, I consider the resource satisfactory | |

| S03 | this type of tools are useful for fostering autonomous learning | |

Participants

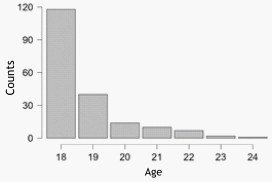

The questionnaire was developed using Google Forms1 and was distributed electronically to students, employing a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method. A total of 192 students participated: 32 from the early childhood education programme (16.6%), 98 from the primary education programme (51%), 34 from the social education programme (17.7%), and 28 from the pedagogy programme (14.5%). In terms of gender, 18.9% were male, 81% were female, and 1% of students did not specify their gender. The average age of the participants in the sample was 18.74 years, with a standard deviation of 1.2 (see Figure 1).

Distribution of the variable age

Data analysis

Initially, the reliability of the tool was analysed based on the results of content validation, obtaining percentages of suitable examples and accurate interactions by ChatGPT. Subsequently, the quality of the prompts was assessed based on student evaluations. In addition to the descriptive analysis of the items from both scales, hypothesis tests for two independent groups were conducted to examine differences in ratings based on student gender and whether ChatGPT made errors during the pilot test. Due to the lack of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test), the Mann–Whitney U test was employed.

Data analyses were performed using the open-source software JASP 18.0.3 (Halter, 2020), with the significance level set at 5%.

RESULTS

Content validation

Table 3 presents the percentage of suitable examples and correct responses obtained from expert judges. Errors were considered as cases in which examples were not clearly understood or did not allow for the accurate identification of the element. According to these criteria, most prompts generated suitable examples, with errors observed only in the identification of variables. Specifically, the machine’s error was making the type of variables explicit along with the proposed example, which prevented students from guessing them. This issue was resolved by instructing ChatGPT to generate a new example without including the types of variables in the text.

| Name of prompt |

Generated example |

Feedback after the response |

| Variables in experimental designs | 83.3 % | 100 % |

| Variables in non-experimental designs | 96.7 % | 100 % |

| Research designs | 100 % | 76.7 % |

| Sampling | 100 % | 63.4 % |

Errors were identified in cases where ChatGPT marked correct student responses as incorrect and vice versa. Errors also included instances in which ChatGPT misidentified the type of example provided or failed to offer sufficient information for the student to respond correctly. In this case, a higher percentage of errors was observed, with errors becoming more frequent as the knowledge bases and instructions included in the prompt were more extensive. Due to the simplicity of the instructions and knowledge base in the variable prompt, the feedback provided to students after attempting to identify examples was correct in all cases. However, in the case of design types, where the program had to correctly identify five distinct types of design categorised into experimental (three types) and non-experimental (two types), the percentage of correct responses decreased to 76.7%. In these cases, errors occurred when generating overly concise statements that did not provide sufficient information to distinguish between the possible designs. There were also instances where the program incorrectly categorised experimental designs as non-experimental. In all cases, the feedback provided by the example-generating machine enabled easy identification of the error. More serious issues were observed with the example-generating machine for sampling. In this case, accurate feedback was provided in 63.4% of cases, with consistent errors in distinguishing between simple random sampling and non-probabilistic convenience sampling. Complete ratings from the judges can be found at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1MZCY8ixi1ZSjA7laAkr3mGZONXDJeFAe/edit?usp=drive_link&ouid=111124780597519622319&rtpof=true&sd=true

To address these errors, given that there were seven different types of samples categorised into probabilistic (three types) and non-probabilistic (four types), it was decided to divide this prompt into two independent ones (one for probabilistic sampling and one for non-probabilistic sampling) to reduce the complexity of the task. These new prompts underwent a second round of validation by the design team, which conducted 90 tests (45 with correct responses and 45 with incorrect responses), and no errors were found.

An example of the prompts’ functionality and their interaction with correct and incorrect student responses for the three main content blocks can be found at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1rJxZwRl6OArsBjdmC7zxEQXfC6zdJWJ0kl89TWERv2s/edit?usp=sharing

Pilot testing

Once the data were collected, a descriptive analysis was performed on the scores obtained for the dimensions of usefulness (McDonald’s Omega = 0.897) and overall satisfaction (McDonald’s Omega = 0.845). The results indicate a positive evaluation of the tool by the students (see Table 4), with mean scores above 7 on all indicators, except for item U09, which concerns the impact of the tool on increasing interest in the content. This item, along with U01 (usefulness for memorisation and reproduction of content), represents the two items with the lowest ratings.

In contrast, indicators U03 and U04, related to the generalisation of content to real-life situations and the resolution of practical problems, received the highest scores in the dimension of usefulness.

Notably, the scores in the dimension of overall satisfaction are striking, as all items received scores above 8, which is consistent with the mean scores of both factors.

| Mean | SD | n | |

| U01 | 7.189 | 1.865 | 190 |

| U02 | 7.812 | 1.656 | 191 |

| U03 | 7.863 | 1.653 | 190 |

| U04 | 7.979 | 1.721 | 190 |

| U05 | 7.641 | 1.713 | 192 |

| U06 | 7.482 | 1.759 | 191 |

| U07 | 7.670 | 1.696 | 191 |

| U08 | 7.674 | 1.736 | 190 |

| U09 | 6.900 | 1.996 | 190 |

| S01 | 8.266 | 1.718 | 192 |

| S02 | 8.272 | 1.341 | 191 |

| S03 | 8.288 | 1.496 | 191 |

| U | 7.595 | 1.275 | 181 |

| S | 8.277 | 1.329 | 190 |

With regard to gender (see Table 5), significant differences were found in three items (U03, U05, and U09), with small effect sizes. In all cases, female students obtained higher mean scores than male students. These items refer to the usefulness of generalising content and applying it to real-life situations (U03), enhancing learning (U05), and increasing interest (U09), respectively. No significant differences were found in the average scores for the two dimensions.

| Group | Mean | SD | n | W | p | d | |

| U03 | Male | 7.286 | 1.655 | 35 | 1928.500 | .008 | -0.280 |

| Female | 7.980 | 1.632 | 153 | ||||

| U05 | Male | 7.083 | 1.519 | 36 | 2023.500 | .010 | -0.270 |

| Female | 7.740 | 1.726 | 154 | ||||

| U09 | Male | 6.222 | 2.179 | 36 | 2120.500 | .029 | -0.230 |

| Female | 7.046 | 1.924 | 153 |

Finally, the influence of the presence of errors during the pilot test was examined. To this end, instructors documented the issues that arose during the demonstration of the prompts’ functionality. In this regard, a few errors were observed in three groups (early childhood education programme, pedagogy programme, and the afternoon group of the primary education programme), while no errors were recorded in the remaining two groups (social education programme and the morning group of the primary education programme). In all cases, the errors were minor issues related to typos in ChatGPT’s feedback, similar to those observed during the validation process, which were used to explain how to identify and correct them.

Table 6 presents the three items for which significant differences were found between the evaluations of students from groups with and without errors. These items referred to the usefulness of memorising and reproducing content (U01), enhancing learning (U05), and increasing interest (U09). Overall, significant differences were found in the dimension of usefulness. In all these cases, students in sessions in which errors were recorded rated the example-generating machines more positively.

| Group | Mean | SD | n | W | p | d | |

| U01 | Without errors | 6.782 | 1.913 | 87 | 3385.500 | 0.003 | -0.244 |

| With errors | 7.534 | 1.759 | 103 | ||||

| U05 | Without errors | 7.295 | 1.716 | 88 | 3463.500 | 0.003 | -0.243 |

| With errors | 7.933 | 1.662 | 104 | ||||

| U09 | Without errors | 6.341 | 1.982 | 88 | 2996.500 | < .001 | -0.332 |

| With errors | 7.382 | 1.888 | 102 | ||||

| U | Without errors | 7.348 | 1.201 | 83 | 2983.500 | 0.002 | -0.266 |

| With errors | 7.804 | 1.304 | 92 |

To reduce sample heterogeneity, it was decided to replicate the previous hypothesis test exclusively with students from the primary education programme, given that students were randomly assigned to the morning or afternoon groups and errors only occurred during the explanation in the afternoon group.

In this case (see Table 7), significant differences were found in five items: the three previously mentioned related to usefulness for memorisation (U01), learning (U05), and interest (U09), as well as two additional items concerning AI’s ability to adapt to the student’s learning pace (U07) and satisfaction with the resource despite its limitations (S02). With regard to the scalar scores, as with the full sample, significant differences were found in the dimension of usefulness. In all cases, students with errors recorded in their sessions rated the example-generating machines more positively.

| Group | Mean | SD | n | W | p | d | |

| U01 | Without errors | 6.352 | 1.925 | 54 | 626.000 | < .001 | -0.473 |

| With errors | 7.864 | 1.850 | 44 | ||||

| U05 | Without errors | 7.333 | 1.671 | 54 | 837.000 | 0.011 | -0.295 |

| With errors | 8.091 | 1.750 | 44 | ||||

| U07 | Without errors | 7.130 | 2.102 | 54 | 905.500 | 0.041 | -0.238 |

| With errors | 7.977 | 1.772 | 44 | ||||

| U09 | Without errors | 6.056 | 2.032 | 54 | 550.500 | < .001 | -0.526 |

| With errors | 7.767 | 1.837 | 43 | ||||

| S02 | No errors | 8.130 | 1.229 | 54 | 908.500 | 0.040 | -0.235 |

| With errors | 8.614 | 1.280 | 44 | ||||

| U | No errors | 7.240 | 1.061 | 51 | 646.000 | 0.001 | -0.397 |

| With errors | 7.963 | 1.375 | 42 |

CONCLUSION

Following the trail of previous studies (Ali et al., 2023; Ayuso-del Puerto & Gutiérrez-Esteban, 2022; Bower et al., 2024; Mao et al., 2024; Mouta et al., 2023; Ruiz-Rojas et al., 2023; Sánchez, 2024), this research aimed to enhance the evidence regarding the effectiveness of generative AI in teaching and learning processes, specifically in the university context. To this end, example-generating machines were created that enabled students in the methods of research in education course to study and review content autonomously through the automatic generation of oriented practical examples.

Addressing the first research question, students rated the tool’s usefulness highly, with overall satisfaction reaching very high levels. However, these results should be interpreted cautiously, as previous studies often revealed that students highly value the integration of technological resources in teaching and learning processes, particularly when these are emerging or disruptive technologies (e.g., Ayala et al., 2023; Cabero-Almenara et al., 2018; Cabero-Almenara & Fernández-Robles, 2018; Ruiz-Campo et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023), such as generative AI. Despite this valuation bias, the high ratings may reflect that students recognise the tool’s potential to self-regulate their learning (Mouta et al., 2023) by adapting to their individual needs and learning paces (Jauhiainen & Guerra, 2023; Ruiz-Rojas et al., 2023), thereby making knowledge transmission more effective (Kuhail et al., 2023).

With regard to the second research question, higher perceived usefulness and satisfaction with the example machine were observed among female students. These results are in contrast with those of previous studies, which typically reveal that men are more enthusiastic and proactive with regard to using new technologies (e.g., Aranda et al., 2019; Ruiz-Campo et al., 2023; Stöhr et al., 2024; Yilmaz et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Specifically, the findings are consistent with those of Raman et al. (2024), according to which women valued the ease of use and direct benefits of ChatGPT more.

This raises questions regarding these results, which might be due to the specific characteristics of students in the field of education sciences. Another possibility is that, unlike other emerging technologies, the nature of generative AI and the manner in which it is interacted with might lead women to feel a greater attachment to and satisfaction with its use. Given the novelty of these effects, an interesting line of research emerges that should be expanded upon in future studies.

With regard to the third research question, unlike other disruptive technologies such as the metaverse (Ruiz-Campo et al., 2023) or augmented reality (Cabero-Almenara et al., 2018; Cabero-Almenara & Fernández-Robles, 2018), the creativity (or margin of error) programmed into generative AI leads it to make mistakes in its interactions. Our results strongly indicated that students who participated in pilot tests in which the machine generated examples with a few errors rated the tool’s usefulness higher and were more satisfied with it. Since this kind of erratic behaviour is not found in other technologies, there are no precedents to guide or justify the results obtained here, beyond the pedagogical effect of the student’s own error and their awareness of it (Krause-Wichmann et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2016). The evidence here suggests that the machine’s errors help students become more aware of these errors, as if they were their own, thereby resulting in a learning effect based on errors.

These results highlight the potential of generative AI tools as support tools for self-learning, presenting example-generating machines developed using ChatGPT and empirically validated to enable students to work on content in a more flexible manner and adapted to their needs and learning paces.

The relevance of these results must be interpreted within the context of the ongoing debate on the societal challenges posed by the inclusion of these technologies and their impact on cultural development (Destéfano et al., 2024). From an educational perspective, generative AIs can be considered technological tools serving a specific task, whose use—particularly from a constructivist perspective—affects human cognition development. This requires focusing not only on short-term outcomes but also on potential medium- or long-term effects (Illera, 2024). In this sense, a few authors have expressed concern regarding the effects of these technologies on critical thinking and written expression (Law, 2024; Thiga, 2024), thereby highlighting the challenging task of developing artificial pedagogy (Díaz & Nussbaum, 2024) capable of addressing the challenges posed by this new educational landscape.

Within this debate, developing activities that integrate example-generating machines and other forms of reactive self-learning, where students must critically analyse AI-generated messages and determine not only the correct answer but also the veracity of the generated information, proves useful in mitigating potential negative effects on critical thinking (Illera, 2024). This utility is evidenced in this study, as students who observed errors and were able to detect and correct them rated the example-generating machines more positively.

Despite demonstrating the usefulness of these resources, this study identified issues that may hinder the integration of these tools into teaching and learning processes. First, there is a lack of training for both teachers and students in the correct use of these tools (Bower et al., 2024; Lo, 2023), not only in basic program handling and prompt generation but also in terms of the risks associated with generative AI tools, such as reliability issues in responses, privacy concerns, and unethical uses (Mintz et al., 2023; Sánchez, 2024). This latter issue was clearly reflected during the pilot test, where students’ lack of awareness of these risks was evident, thereby leading to debates on issues such as the inability to generate real bibliographic citations ( Karakose, 2023), the probabilistic nature of the algorithm (Kortemeyer, 2023), or hallucinations (Amézquita Zamora, 2023).

Second, problems were encountered related to the selected generative AI tool’s ability to handle logical processes and interact with users, which complicated prompt development. Although generative AI tools have great potential to transform human activities and alter teaching and learning processes, they are still in early development stages and need to continue evolving and improving their natural interactions (Jauhiainen & Guerra, 2023).

This study also has a few significant limitations. With regard to research design, the student sample comes from a single university and field of study, which limits the generalizability of the results. Additionally, an evaluative research approach was used with limited control over variables, thus making it difficult to establish causal relationships. Finally, due to the limitations of the duration of the pilot test and the evaluative nature of the research, only students’ perceptions could be analysed, leaving the impact of using example-generating machines on student performance unexamined.

With regard to tool limitations, interaction problems with users, difficulty executing complex operations, and occasional errors in example generation were notable. Additionally, ChatGPT’s adaptation to each subject’s conversational and communicative style caused prompts to function differently for each user, thereby increasing the likelihood of errors. It is also important to consider that the prompts were designed for the free and widely known version 3.5 of ChatGPT, although reliance on this version constitutes a limitation for future considerations.

The results and limitations identified here open avenues for future research. With regard to design, it is suggested to expand the sample to other populations and apply designs with higher levels of control and experimentation, incorporating performance measures. For the tool, it is of interest to continue refining example-generating machines, using more advanced generative AIs to achieve more complete, integrated, and error-free examples as well as designing a prompt that works across different generative AIs to reduce dependence on specific tool versions. Another future direction could be improving user experience through specific software that communicates with the AI via an API and integrates it into the institutional virtual campus. Finally, given the obtained results, it would be interesting to explore the effect of errors on the adoption of generative AI tools in educational contexts and further study gender differences in the satisfaction with using these tools.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, N., Murugesan, S., & Kshetri, N. (2023). Generative Artificial Intelligence and the Education Sector. Computer, 56(6), 72-76. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2023.3263576

Alam, F., Lim, M. A., & Zulkipli, I. N. (2023). Integrating AI in Medical Education: Embracing Ethical Usage and Critical Understanding. Frontiers in Medicine, 10, Article 1279707. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1279707

Ali, J., Shamsan, M. A. A., Hezam, T., & Mohammed, A. A. Q. (2023). Impact of ChatGPT on learning motivation: Teachers and students' voices. Journal of English Studies in Arabia Felix, 2(1), 41-49. https://doi.org/10.56540/jesaf.v2i1.51

Amézquita Zamora, J. A. (2023). Uso responsable de ChatGPT en el aula: Cómo convertirlo en un aliado en los procesos educativos. Company Games & Business Simulation Academic Journal, 3(2), 69-86. http://uajournals.com/ojs/index.php/businesssimulationjournal/article/view/1511

Aranda, L., Rubio, L., Di Giusto, C., & Dumitrache, C. (2019). Evaluation in the use of TIC in students of the University of Malaga: gender differences. INNOEDUCA. International Journal of Technology And Educational Innovation, 5(1), 63-71. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2019.v5i1.5175

Ayala, E., López, R. E., & Menéndez, V. H. (2023). Implementación holística de tecnologías digitales emergentes en educación superior. Edutec. Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa, (83), 153-172. https://doi.org/10.21556/edutec.2023.83.2707

Ayuso-del Puerto, D., & Gutiérrez-Esteban, P. (2022). La Inteligencia Artificial como Recurso Educativo durante la Formación Inicial del Profesorado. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 25(2), 347-362. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.25.2.32332

Bower, M., Torrington, J., Lai, J. W. M., Petocz, P., & Alfano, M. (2024). How should we change teaching and assessment in response to increasingly powerful generative Artificial Intelligence? Outcomes of the ChatGPT teacher survey. Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12405-0

Brailas, A. (2024). Postdigital Duoethnography: An Inquiry into Human-Artificial Intelligence Synergies. Postdigital Science and Education, 6, 486-515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-024-00455-7

Cabero-Almenara, J., & Fernández-Robles, B. (2018). Las tecnologías digitales emergentes entran en la Universidad: RA y RV. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 21(2), 119-138. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.21.2.20094

Cabero-Almenara, J., Vázquez-Cano, E., & López-Meneses, E. (2018). Uso de la Realidad Aumentada como Recurso Didáctico en la Enseñanza Universitaria. Formación Universitaria, 11(1), 25-34. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062018000100025

Cascella, M., Montomoli, J., Bellini, V., & Bignami, E. (2023). Evaluating the Feasibility of ChatGPT in Healthcare: An Analysis of Multiple Clinical and Research Scenarios. Journal of Medical Systems, 47(1), Article 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-023-01925-4

Chaudhry, M. A., & Kazim, E. (2022). Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIEd): a high-level academic and industry note 2021. AI and Ethics, 2(1), 157-165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00074-z

Choi, E. P. H., Lee, J. J., Ho, M. H., Kwok, J. Y. Y., & Lok, K. Y. W. (2023). Chatting or cheating? The impacts of ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence language models on nurse education. Nurse Education Today, 125, Article 105796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105796

Cooper, G. (2023). Examining Science Education in ChatGPT: An Exploratory Study of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 32(3), 444-452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-023-10039-y

Copeland, B. (2023). Artificial intelligence (AI). Definition, Examples, Types, Applications, Companies, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/artificial-intelligence

Deike, M. (2024). Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT and Perplexity AI in Business Reference. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 29(2), 125-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2024.2317534

Destéfano, M., Trifonova, A., & Barajas, M. (2024). Teaching AI to the next generation: A humanistic approach. Digital Education Review, 45, 115-123.https://doi.org/10.1344/der.2024.45.115-123

Díaz, B., & Nussbaum, M. (2024). Artificial intelligence for teaching and learning in schools: The need for pedagogical intelligence. Computers & Education, 217, Article 105071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2024.105071

Eysenbach, G. (2023). The role of ChatGPT, generative language models, and artificial intelligence in medical education: A conversation with ChatGPT and a call for papers. JMIR Medical Education, 9(1), Article e46885. https://doi.org/10.2196/46885

González, R. A., & Silveira, M. H. (2022). Educación e Inteligencia Artificial: Nodos temáticos de inmersión. Edutec. Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa, 82, 59-77. https://doi.org/10.21556/edutec.2022.82.2633

Guan, C., Mou, J., & Jiang, Z. (2020). Artificial intelligence innovation in education: A twenty-year data-driven historical analysis. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 4(4), 134-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijis.2020.09.001

Halter, C. P. (2020). Quantitative Analysis: With JASP open-source software. Independently published.

Hirsch-Kreinsen, H. (2023). Artificial intelligence: A “promising technology”. AI & Society. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01629-w

Hsu, Y. C., & Ching, Y. H. (2023). Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education, Part One: the Dynamic Frontier. TechTrends, 67, 603-607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00863-9

Illera, J. (2024). AI in the discourse of the relationships between technology and education. Digital Education Review, 45, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1344/der.2024.45.1-7

Jauhiainen, J. S., & Guerra, A. G. (2023). Generative AI and ChatGPT in School Children's Education: Evidence from a School Lesson. Sustainability, 15(18), Article 14025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151814025

Kalota, F. (2024). A Primer on Generative Artificial Intelligence. Education Sciences, 14(2), Article 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020172

Karakose, T. (2023). The utility of ChatGPT in educational research—potential opportunities and pitfalls. Educational Process: International Journal, 12, 7-13. https://doi.org/10.22521/edupij.2023.122.1

Karakose, T., Demirkol, M., Yirci, R., Polat, H., Ozdemir, T. Y., & Tülübaş, T. A. (2023). A conversation with ChatGPT about digital leadership and technology integration: Comparative analysis based on human–AI collaboration. Administrative Sciences, 13(7), Article 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13070157

Kennedy, B., Tyson, A., & Saks, E. (2023). Public awareness of artificial intelligence in everyday activities: Limited enthusiasm in U.S. over AI’s growing influence in daily life. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2023/02/15/public-awareness-of-artificial-intelligence-in-everyday-activities/

Kortemeyer, G. (2023). Could an artificial-intelligence agent pass an introductory physics course? Physical Review Physics Education Research, 19(1), Article 010132. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.19.010132

Korzynski, P., Mazurek, G., Krzypkowska, P., & Kurasniski, A. (2023). Artificial intelligence prompt engineering as a new digital competence: Analysis of generative AI technologies such as ChatGPT. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 11(3), 25-37. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2023.110302

Krause-Wichmann, T., Greisel, M., Wekerle, C., Kollar, I., & Stark, R. (2023). Promoting future teachers’ evidence-informed reasoning scripts: Effects of different forms of instruction after problem-solving. Frontiers in Education, 8, Article 1001523. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1001523

Kuhail, M. A., Alturki, N., Alramlawi, S., & Alhejori, K. (2023). Interacting with educational chatbots: A systematic review. Education and Information Technology, 28, 973-1018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11177-3

Law, L. (2024). Application of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) in language teaching and learning: A scoping literature review. Computers and Education Open, 6, Article 100174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100174

Ling, J., & Afzaal, M. (2024). Automatic question-answer pairs generation using pre-trained large language models in higher education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, Article 100252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100252

Lo, C. K. (2023). What Is the Impact of ChatGPT on Education? A Rapid Review of the Literature. Education Sciences, 13(4), Article 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040410

Mah, C., & Levine, S. (2023, February 19). How to use ChatGPT as an example machine. Cult of Pedagogy. https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/chatgpt-example-machine/

Mao, J., Chen, B. Y., & Liu, J. C. (2024). Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education and Its Implications for Assessment. Techtrends, 8(1), 58-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00911-4

Martinez, D., Malyska, N., Streilein, B., Caceres, R., Campbell, W., Dagli, C., Gadepally, V., Greenfield, K., Hall, R., King, A., Lippmann, R., Miller, B., Reynolds, D., Richardson, F., Sahin, C., Tran, A., Trepagnier, P., & Zipkin, J. (2019). Artificial intelligence: Short history, present developments, and future outlook. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Martínez-Abad, F., & Hernández-Ramos, J. P. (2017). FlippedClassroom con píldoras audiovisuales en prácticas de análisis de datos para la docencia universitaria: Percepción de los estudiantes sobre su eficacia. In S. Pérez Aldeguer, G. Castellano Pérez, & A. Pina Calafi (Eds.), Propuestas de Innovación Educativa en la Sociedad de la Información (pp. 92-105). AdayaPress. https://doi.org/10.58909/ad17267178

Mintz, J., Holmes, W., Liu, L., & Perez-Ortiz, M. (2023). Artificial Intelligence and K-12 Education: Possibilities, Pedagogies and Risks. Computers in the Schools, 40(4), 325-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2023.2279870

Mouta, A., Pinto-Llorente, A. M., & Torrecilla-Sánchez, E. M. (2023). Uncovering Blind Spots in Education Ethics: Insights from a Systematic Literature Review on Artificial Intelligence in Education. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00384-9

Nash, B. L., Hicks, T., Garcia, M., Fassbender, W., Alvermann, D., Boutelier, S., McBride, C., McGrail, E., Moran, C., O'Byrne, I., Piotrowski, A., Rice, M., & Young, C. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in English Education: Challenges and Opportunities for Teachers and Teacher Educators. English Education, 55(3), 201-206. https://doi.org/10.58680/ee202332555

Olmos, S., Martínez-Abad, F., Torrecilla, E. M., & Mena, J. J. (2014). Análisis psicométrico de una escala de percepción sobre la utilidad de Moodle en la universidad. RELIEVE - Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 20(2), Artículo 1. https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.20.2.4221

Pavlik, J. V. (2023). Collaborating with ChatGPT: Considering the implications of generative artificial intelligence for journalism and media education. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 78(1), 84-93. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776958221149577

Petricini, T. (2024). What would Aristotle do? Navigating generative artificial intelligence in higher education. Postdigital Science and Education, 6, 439-445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-024-00463-7

Raman, R., Mandal, S., Das, P., Kaur, T., Sanjanasri, J. P., & Nedungadi, P. (2024). Exploring University Students’ Adoption of ChatGPT Using the Diffusion of Innovation Theory and Sentiment Analysis with Gender Dimension. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2024, Article 085910. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/3085910

Rebelo, A. D. P., Inês, G. D. O., & Damion, D. V. (2022). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Creativity of Videos. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMM), 18(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3462634

Reynolds, L., & McDonell, K. (2021). Prompt Programming for Large Language Models: Beyond the Few-Shot Paradigm. In Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 314). Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). https://doi.org/10.1145/3411763.3451760

Ruiz-Campo, S., Matías-Batalla, D., Boronat-Clavijo, B., & Acevedo-Duque, Á. (2023). Los metaversos como herramienta docente en la formación de profesores de educación superior. RELATEC. Revista Latinoamericana de Tecnología Educativa, 22(1), 135-153. https://doi.org/10.17398/1695-288X.22.1.135

Ruiz-Rojas, L. I., Acosta-Vargas, P., De-Moreta-Llovet, J., & Gonzalez-Rodriguez, M. (2023). Empowering Education with Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools: Approach with an Instructional Design Matrix. Sustainability, 15(15), Article 11524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511524

Saif, N., Khan, S. U., Shaheen, I., ALotaibi, F. A., Alnfiai, M. M., & Arif, M. (2024). Chat-GPT; validating Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in education sector via ubiquitous learning mechanism. Computers in Human Behavior, 154, Article 108097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108097

Sánchez, M. M. (2024). La inteligencia artificial como recurso docente: usos y posibilidades para el profesorado. Educar, 60(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/educar.1810

Stöhr, C., Ou, A. W., & Malmström, H. (2024). Perceptions and usage of AI chatbots among students in higher education across genders, academic levels and fields of study. Computers and Education. Artificial Intelligence, 7, Article 100259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100259

Stokel-Walker, C., & Nordeen, V. R. (2023). The promise and peril of generative AI. Nature, 614, 214-216. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00340-6

Surden, H. (2019). Artificial intelligence and law: An overview. Georgia State University Law Review, 35(4), 1305-1337. https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol35/iss4/8

Thiga, M. M. (2024). Generative AI and the development of critical thinking skills. Iconic Research and Engineering Journals, 7(9), 83-90. https://bit.ly/3WEyQRt

Trust, T., & Maloy, R. W. (2023). AI in the history classroom: Strategies for rethinking teaching and learning. Teaching History, 57(3), 10-15. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.322842139237015

UNESCO. (2021). Artificial Intelligence and Education. Guidance for Policy-makers. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://doi.org/10.54675/PCSP7350

Williams, C. K., Tremblay, L., & Carnahan, H. (2016). It pays to go off-track: Practicing with error-augmenting haptic feedback facilitates learning of a curve-tracing task. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 2010. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02010

Yilmaz, H., Maxutov, S., Baitekov, A., & Balta, N. (2023). Student attitudes towards chat GPT: a technology acceptance model survey. International Educational Review, 1(1), 57-83. https://doi.org/10.58693/ier.114

Zhang, C., Schießl, J., Plößl, L., Hofmann, F., & Gläser-Zikuda, M. (2023). Acceptance of artificial intelligence among pre-service teachers: a multigroup analysis. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20, Article 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00420-7

Notes

Reception: 01 June 2024

Accepted: 01 August 2024

OnlineFirst: 23 September 2024

Publication: 01 January 2025