Estudios e investigaciones / Research and Case Studies

Virtual reality to assess classroom management competence: a study on conflict management

Realidad virtual para evaluar la competencia en gestión del aula: estudio sobre afrontamiento de conflictos

Virtual reality to assess classroom management competence: a study on conflict management

RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, vol. 28, núm. 1, 2025

Asociación Iberoamericana de Educación Superior a Distancia

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional.

How to cite: Alvarez, I. M., Morodo, A., Romero-Hernández, A., & Manero, B. (2025). Virtual reality to assess classroom management competence: a study on conflict management. [Realidad virtual para

evaluar la competencia en gestión del aula: estudio sobre afrontamiento de conflictos]. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a

Distancia, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.28.1.41472

Abstract: This study underscores the importance of using realistic scenarios to assess Classroom Management Competence (CMC), which has traditionally been measured through questionnaires. The CMC of preservice secondary school teachers was assessed using Didascalia Virtual Classroom, a virtual reality simulation platform designed to foster this competence. The study aimed to identify and categorize the coping strategies employed by preservice teachers to manage incidents within an Immersive Virtual Reality environment. Conducted as part of a teacher training Master’s programme, the study involved 39 students from eight disciplines from two Spanish universities. Three simulated scenarios were designed to represent disruptive behaviours: disturbances in teacher-student relationships, conflicts between classmates, and issues during group work. A mixed-methods approach with an exploratory-descriptive perspective was used. Data were collected through videos of the participants' actions, which were then analysed using thematic content analysis based on Thomas y Kilmann's (2008) conflict management styles: collaboration, compromise, accommodation, avoidance, and domination. The results indicated that participants tended to employ more assertive and reactive strategies, such as domination and compromise. Two distinct subgroups emerged: one assertive but uncooperative, and another with low assertiveness and moderate cooperation. Differences in strategy implementation were observed across scenarios, suggesting that future teachers need to develop flexibility in classroom management by adopting a proactive approach and tailoring strategies to various contexts and types of disruptive behaviour.

Keywords: classroom management, conflict management strategies, virtual reality, secondary education.

Resumen: Este estudio subraya la importancia de utilizar escenarios realistas para evaluar la Competencia en Gestión de Aula (CGA), tradicionalmente medida mediante cuestionarios. Se evaluó la CGA de futuros docentes de secundaria con Didascalia Virtual Classroom, una plataforma de simulaciones en realidad virtual para fomentar esta competencia. El objetivo fue identificar y categorizar las estrategias de afrontamiento del profesorado en formación para gestionar incidentes en un entorno de Realidad Virtual Inmersiva. El estudio, realizado en el máster de formación del profesorado, incluyó a 39 estudiantes de ocho disciplinas de dos universidades españolas. Se diseñaron tres escenarios simulados que representaban comportamientos disruptivos: perturbaciones en la relación profesor-alumno, entre compañeros y durante el trabajo en grupo. Se utilizó un enfoque metodológico mixto con una aproximación exploratoria-descriptiva. Los datos se recogieron mediante vídeos de las actuaciones de los participantes y se realizó un análisis de contenido temático basado en los estilos de gestión de conflictos de Thomas y Kilmann (2008): cooperación, compromiso, complacencia, evitación y dominación. Los resultados mostraron que los participantes tendían a usar estrategias asertivas y reactivas, como dominación y compromiso. Se identificaron dos subgrupos con perfiles distintos: uno asertivo, pero no cooperativo y otro con baja asertividad y moderada cooperación. Se observaron diferencias en la implementación de estrategias según los escenarios. Esto sugiere que los futuros docentes deben desarrollar flexibilidad en la gestión del aula, adoptando un enfoque proactivo y adaptando estrategias a diferentes contextos y comportamientos disruptivos.

Palabras clave: gestión del aula, estrategias de gestión de conflictos, realidad virtual, educación secundaria.

INTRODUCTION

Minor student misbehaviour is a common concern among teachers (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008; OECD, 2020; Tarantul & Berkovich, 2024). However, most of the research on classroom management strategies focuses on perceived self-efficacy and does not sufficiently address the relationship between these strategies and the communicative dynamics that trigger critical incidents (McGuire et al., 2024). Undeniably, the complexity of a classroom setting proves difficult to simulate in practice scenarios for future teachers, who should be ready to face the challenges and tensions of the real environment.

This study proposes the use of an immersive virtual reality environment (IVRE) to assess classroom management competence (CMC), looking specifically at the coping styles adopted by trainee teachers. The use of the IVRE is expected to provide a richer and more contextualised view of the proactive and reactive management strategies employed by participants. This platform will not only assess CMC more effectively than traditional self-efficacy questionnaires, but it will also provide an innovative tool for teacher training and professional development

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The following section is framed in the context of classroom conflict management. Firstly, we will discuss the notion of classroom management, and secondly, we will analyse the educational potential of virtual reality in teacher training.

Ecological approach to classroom climate and classroom conflict

In education, classroom climate is a dynamic phenomenon that manifests itself in the interactions between teachers and students. According to Wang et al. (2019), this climate can be understood along three dimensions: academic-instructional (teaching-learning methodologies), socio-emotional (emotional exchanges) and organisational (management of disruptive behaviour), the last of which is the focus of this study.

Sarceda-Gorgoso et al. (2020) found that only 19.8% of prospective teachers in Spain considered themselves to be very competent in classroom management at the beginning of their Master's programme in Teacher Training, whereas at the end of the programme only 34% assessed themselves with the highest score. Buendía-Eisman et al. (2015) found that students preferred integrative and avoidant strategies, while teachers predominantly used coercive techniques. This finding highlights the need for more effective training in conflict resolution strategies.

From an ecological perspective, classroom climate management requires foresight and strategic planning to support holistic student learning (Doyle, 2006; Evertson & Poole, 2012), an approach that goes beyond the mere transmission of knowledge. Specifically, proactive strategies that address the causes of specific behaviours within the classroom ecosystem are essential to maintaining a positive learning environment (Alasmari & Althaqafi, 2021).

Conflict is seen as a specific form of communication; namely, an expressed contradiction that blocks communication (Luhmann, 1982). When conflict disrupts classroom communication, it affects interpersonal relationships and can lead to disruptive events that hinder teaching (Bingham et al., 2009).

It is important to consider these aspects when assessing CMC, as they underline the need for multifaceted skills: from understanding social and emotional dynamics to the ability to adapt to unforeseen situations and manage conflict effectively, all within an environment of mutual trust and accountability between teachers and students.

Challenges in classroom management and strategies for a positive climate

In general terms, classroom management refers to the actions teachers take to establish order, encourage student participation and elicit their cooperation (Emmer & Stough, 2003). This management is inherently complex, as both teachers and students play a role in establishing classroom order and a variety of circumstances can affect classroom dynamics. Effective conflict management cannot be reduced to standardised behaviours, which is a common approach in traditional teacher education (Christofferson & Sullivan, 2015).

While some studies support reactive classroom management (Canter & Canter, 2001; Olafson & Schraw, 2006), there is a growing preference for proactive and less authoritarian approaches (Evertson & Poole, 2012; Gross, 2015). This evolution reflects a trend towards a pedagogy that fosters both academic engagement and personal development of learners (Cook et al., 2018; Santiago-Rosario et al., 2023).

Kounin's (1970) influential study concluded that teachers who were aware of classroom behaviours and were able to multi-task, maintain lesson momentum and keep their students engaged, experienced fewer instances of inappropriate behaviour. Evertson and Weinstein (2013) argue that those who plan responses to problem behaviours through proactive strategies spend less time on dealing with disruptions.

‘Assertive discipline' (Canter & Canter, 2001) highlights the need to establish a clear and structured approach to classroom management. This method involves designing a systematic discipline plan before the start of the school year, communicating expectations and consequences to the students, setting precise and consistent rules, reinforcing positive behaviours through rewards and enforcing appropriate consequences for non-compliance, as well as engaging students in the collaborative implementation of the plan.

Assertive communication is an essential skill for teachers, as it involves a firm, positive and respectful tone, as well as demonstrating confidence and consistent expectations (Iglesias-Díaz & Romero-Pérez, 2021; Inbar-Furst et al., 2021) by setting clear boundaries and expressing opinions appropriately. However, the long-term effectiveness of disciplinary approaches raises questions. Although they may control problem behaviours in the short term, they do not ensure their eradication. Some students may adapt to sanctions or avoid detection, which does not necessarily contribute to meaningful learning (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008; Payne, 2015). Empathy, on the other hand, is key in teachers' response to disruptive behaviour, as by promoting understanding and support, teachers can effectively address the underlying causes and create a more positive and productive classroom environment (Keller & Becker, 2020; McGrath & Van Bergen, 2019).

Strategies involving domination (issuing verbal reprimands or sanctions), and avoidance (ignoring confrontation) are less effective for classroom climate management and emotional regulation in conflict situations (Gross, 2015, Martinez et al., 2020). These strategies often do not adequately address the underlying causes of disruptive behaviour and may worsen the situation.

Teachers' aggressive responses to disruptive behaviour can negatively affect the classroom environment. Acting in a hostile manner can humiliate students and create a tense and unwelcoming environment (Davis, 2017). Abuse of authority by teachers has a significant psychological impact on students, affecting their emotional well-being and their attitude towards school and learning (Campbell, 2004).

Therefore, it is essential to promote coping styles that integrate assertiveness and cooperation to foster a positive school climate and effectively manage conflict in the educational environment (Govorova et al., 2020). The use of proactive strategies and empathy in classroom management promotes a more positive and productive learning environment.

Assessing classroom conflict management strategies: the potential of IVR for authentic assessment

Although, as we have seen, there is some consensus on the definition of classroom management, the subject remains a matter of debate, especially in terms of its composition and the indicators used for its assessment (Sabornie & Espelage, 2023).

Thomas and Kilmann's (2008) model, which is widely recognised in research on teaching strategies for managing classroom conflict, describes conflict and negotiation in two dimensions: assertiveness and cooperativeness. Within these dimensions, five conflict management strategies are identified: collaboration (finding a middle ground that satisfies the parties), compromise (dialogue to reach consensus), accommodation (teachers give in and adopt the students' position), avoidance (ignoring disruptive behaviour) and domination (reprimands or punishments).

The study by Zurlo et al. (2020) investigated conflict management styles of teachers in five European countries using a questionnaire. The findings showed that teachers with a multi-strategic and engaged conflict management style reported higher abilities to achieve relational and educational goals. In contrast, those with a dominating and avoiding style tended to use authoritarian strategies to deal with disruptions quickly, which can exacerbate conflicts and create a hostile classroom climate.

More recent studies have shown that strategies that combine assertiveness and cooperativeness are often the most effective (e.g. Tarantul & Berkovich, 2024), as they allow teachers to address both their own needs and those of their students, promoting an atmosphere of mutual respect and constructive problem solving. In contrast, strategies such as avoidance and domination can perpetuate conflict and erode trust in the teacher-student relationship.

Simulating the complexity of a classroom in an authentic and safe practice setting is a challenge. IVR offers a safe immersive experience, allowing users to interact realistically with simulated environments (Ke et al., 2020). This provides trainee teachers with life-like experiences, developing CMC in a controlled environment. In addition, immersive environments facilitate immediate feedback and observation of strategies in action ( McGarr, 2021 ), improving the validity of assessment, reducing bias and supporting continuous professional development (Hamilton et al., 2021).

Although the use of various IVR simulations for in-service teacher education has been investigated (e.g., Kugurakova et al., 2023; Lugrin et al., 2016; Seufert et al., 2022), in the literature reviewed, there are no studies using IVR for classroom management analysis.

The aim of this study is to identify and categorise the coping strategies that trainee teachers employ to manage classroom incidents in three different communicative scenarios simulated in an IVRE.

METHOD

A mixed-methods approach (Fraenkel et al., 2018) combining quantitative and qualitative techniques was employed. The study adopted a descriptive and objective approach, focusing on coding and statistical analysis of the data. Participants interacted in the IVRE and their actions were recorded and analysed according to Thomas and Kilmann's (2008) conflict management categories. The analysis focused primarily on quantification and categorisation, but also included a qualitative dimension to contextualise and enrich the results with illustrative quotes from the participants. Although this qualitative approach introduces some subjectivity, it provides a deeper understanding of the dynamics observed in the IVRE.

Context and participants

The research was conducted with 39 students enrolled in the Psychology module, which is part of the Psychopedagogical and Social Training strand of the Master's Degree in Secondary Education Teacher Training at Spanish universities. The participants were selected intentionally (based on their voluntary participation), after obtaining their informed consent. The students came from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (43.6%) and the Complutense University of Madrid (56.4%) and represented various disciplines: Visual Arts and Music (17.9%), Social Sciences (33.3%), Basic Sciences (10.3%) and Languages (30.8). 53.8% were male, and the average age of participants was 25.6 years.

Description of the immersive virtual reality environment

Didascalia VC is an IVR learning environment that allows trainee teachers to experience, record and reflect on key aspects of effective conflict management in the classroom. The platform recreates conflict situations based on an analysis of 1411 discipline reports from schools in Madrid and Barcelona (Masó, 2022).

In a typical session, the user is asked to start teaching a class. During the simulation, disruptive behaviours occur, such as students making inappropriate comments or a student refusing to follow instructions. These behaviours are simulated in three different scenarios:

Scenario 1: Disruptive situations that affect the teacher-student relationship. For example, a student interrupts the teacher's explanation by making a derogatory comment such as "What a load of bullshit".

Scenario 2: Disruptive situations arising from interactions between classmates. For example, two students refuse to follow the established rules and defy previous warnings by refusing to separate and making defiant gestures.

Scenario 3: Disruptive situations caused by conflicts during group work. For example, a learner stands up and leaves the group verbalising his/her displeasure.

The participant responds to the disruptive situation and the system captures his/her reaction through his/her tone of voice, volume, speech content and position in the virtual classroom. This reaction is processed and elicits a response from the virtual learners.

The previous validation of Didascalia VC as a promising training scenario (Álvarez et al., 2023) underlines the relevance of this research. Currently, Didascalia VC is in a laboratory component validation stage and is a non-commercial prototype under review. Bocos-Corredor et al. (2020) provide a detailed explanation of its architecture and features. Results from user testing show that the majority of participants accepted the illusion of the IVR and behaved similarly to how they would in a real classroom (Álvarez et al., 2024).

Research design

Stage 1. Introduction. In this initial phase, participants were welcomed and asked to sign the informed consent form. They were given a brief demonstration on the use of the IVR equipment, and on the scenarios and conflicts that were simulated on the platform, explaining that the aim of the study was to analyse how they managed these conflicts.

Stage 2. Interaction with IVRE. During this stage, organised in groups of 4 or 5, the participants interacted with the IVRE. In turns, one participant from each group carried out the practice, lasting approximately 15 minutes per person. Each participant was confronted with disruptive situations within the IVRE, which they had to manage by applying the strategies they considered appropriate. This study focuses on the analysis of the data obtained during this stage.

Stage 3. Focus groups. After having participated in the IVRE, each group reflected on the practice, in a focus group format. They were provided with a script with questions and key issues to guide the discussion.

Procedure for data collection and analysis

Camtasia was used to record the data, capturing the screen (video) and audio of the simulation in the IVRE. The unit of analysis was the participants' experience of the three simulated scenarios (n=117).

A thematic content analysis was conducted (Braun & Clarke, 2021), using five main categories based on Thomas and Kilmann's (2008) conflict management styles: collaboration, compromise, accommodation, avoidance and domination. The strategies employed by participants in the different simulated scenarios were manually coded using Atlas.ti (v.24.0). A detailed codebook, including descriptions, interpretations and examples of each code, is provided in the supplementary material1.

Quantitative data, including frequencies of coded categories, were analysed using descriptive statistics in SPSS (version 22.0). Ward's clustering method, recommended for categorical variables (Hair et al., 2019), was used to analyse trends across subjects according to coping styles in the three simulated scenarios.

The study was developed through several sequential analytical steps:

- 1. Descriptive statistics analysis to examine the frequency with which participants implemented various coping strategies throughout the experience.

- 2. Chi-square test for each simulated communicative scenario. The aim here was to determine whether there was a significant link between participants and the predominant patterns of conflict management in the different scenarios. This test helped to identify whether participants had different preferences in terms of coping strategies depending on the context.

- 3. Cluster analysis to group participants into profiles or clusters according to the coping strategies they employed. Once these subgroups were identified, their conflict management patterns were compared to explore possible significant differences in the implementation of coping strategies in different scenarios.

- 4. Analysis of the evolution of the different strategies throughout the experience. This was achieved through the use of descriptive statistics and visual trend analysis, allowing for a deeper understanding of how participants' coping strategies changed.

RESULTS

The results of this study are presented below following the order of the procedure described for the analysis of the results.

Frequency analysis of coping strategies

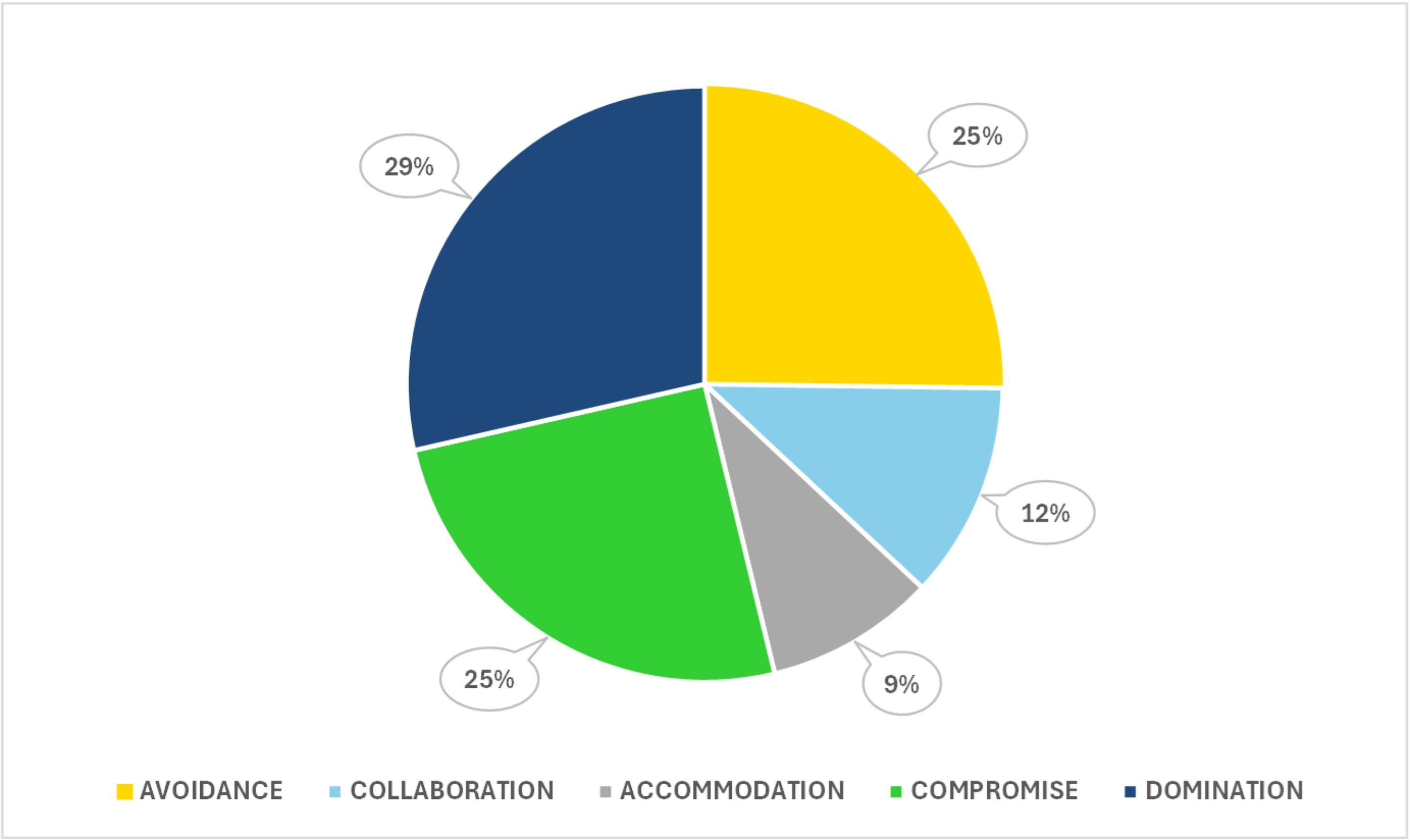

The overall results indicate that, in general, participants mainly implemented the strategies Domination (29%) and Compromise (25%), characterised as more assertive. The high frequency of the Avoidance strategy (25%) is striking, as well as the low frequency of the implementation of Collaboration (12%), found in only 14 cases out of the 117 coded experiences.

Overall summary of strategies used

Note: The graph shows the percentage of quotes coded in the five categories, for the whole experience (n=117).

Results in the simulated communicative scenarios

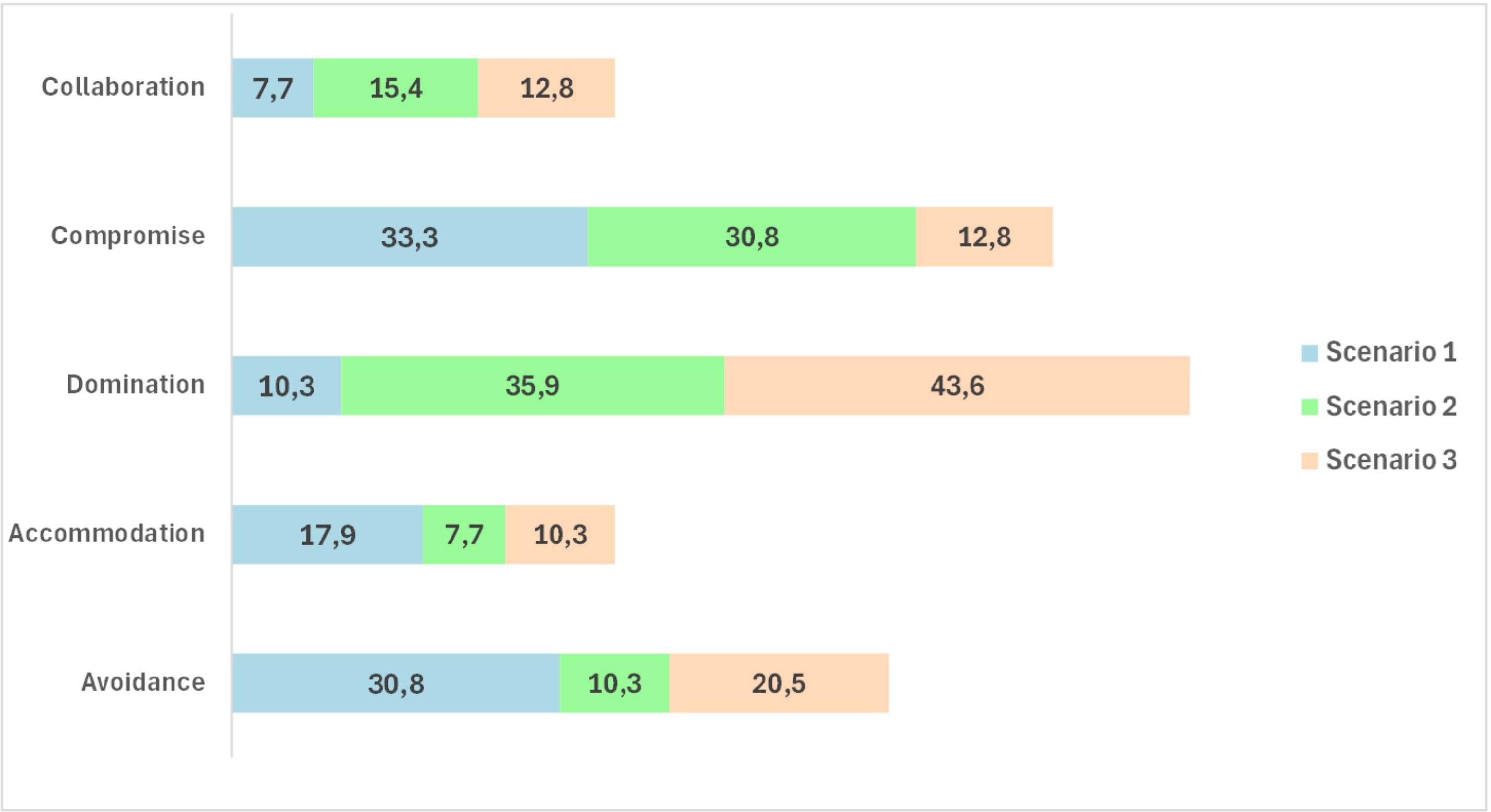

In the first scenario, Compromise and Avoidance strategies were predominant. Participants showed an active approach to problem solving, although some participants were also observed to avoid conflict situations.

In the second scenario, we observed a combination of Domination and Compromise. Participants tried to take control of the situation but were also willing to collaborate.

In the third scenario, the Domination strategy was more evident. Participants adopted a more authoritarian stance and focused on imposing their will. Figure 2 presents the details of this analysis.

Distinguishing the strategies used in the different scenarios

Note: The graph shows the percentage of quotes coded in the five categories for each scenario (S). S1: Disruptive situations in the teacher-student relationship; S2: Disruptive situations between classmates; S3: Disruptive situations during group work.

Exploring differences between participants in the different scenarios

The cluster analysis allowed us to identify two distinctive profiles among the participants. The first group (subgroup 1, n=19, 48.7%) was characterised as predominantly assertive, but not cooperative, showing a high frequency in the application of reactive coping strategies, especially Domination and/or Compromise. On the other hand, the second profile (subgroup 2, n=20, 51.3%) grouped participants who employed strategies with low assertiveness and moderate cooperation, with Accommodation and Avoidance being more common than in subgroup 1.

To analyse the association between participants and the different simulated conflict scenarios, a Chi-square test was performed. The results highlighted a significant link between these variables in the second (χ^2(4, 39) =.495, p=.013) and third scenarios (χ^2(4, 39) =.617, p=.000), which dealt with disruptive situations between two students and group conflicts, respectively. This link suggests that participants in both groups differ in the strategies used to manage conflict in these specific circumstances.

In the first scenario (disturbances affecting the teacher-student relationship: inappropriate comment from a student) no statistically significant differences were observed. However, participants in subgroup 1 most frequently used reactive coping strategies related to the assertive-non-cooperative style, resorting to Compromise (47.4%), while in subgroup 2 one third (35%) opted for Avoidance (see details in Table 1).

The following quotes illustrate the predominant coping styles in both groups for managing the simulated incident in the first scenario:

Scenario 1: Inappropriate comment from a student.

Quote 1 (Compromise, Subgroup 1, Computer Science): Hi, I'm Salva, I'm going to teach you Computer Science and I would like you to introduce yourselves. OK, nobody wants to take part. So, I'm going to introduce myself. Incident arises (a student shouts 'asshole!'). Let's see. We're off to a bad start, I'm not going to tolerate this kind of attitude in class. OK, does anyone want to say anything or do you want me to introduce myself? [D.17_0:02-1:31, P.17] (D: document, P: participant).

Quote 2 (Avoidance, Subgroup 2, Languages): Good morning, how are you? How are we today? We are going to have a lesson on Music. We will start with the treble clef... Incident arises (a student shouts 'what a load of bullshit'). Everything OK? (teacher asks and continues her presentation) Well, let's move on if everything is OK..." [D39_0:28-2:57, P28]

Both quotes offer insight into the predominant coping styles used by the respective groups to manage the simulated incident in the initial scenario. In the first (subgroup 1) a Compromise approach is observed. The teacher directly addresses the incident, setting clear boundaries about acceptable behaviour in class. Although students remain silent, the teacher continues to try to encourage participation and dialogue, showing a willingness to understand the reasons behind the disruptive behaviour. In contrast, the second quote (subgroup 2) reveals an avoidance strategy. After the incident, the teacher chooses not to address it directly and continues with the class as if nothing had happened, ignoring the disruptive behaviour. This attitude suggests a preference for avoiding conflict and maintaining apparent harmony in the classroom, even if the underlying problem is not adequately addressed.

| Avoidance | Accommodation | Domination | Compromise | Collaboration | |

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | |

| Subgroup 1 | 5 (26.3) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (5.3) | 8 (47.4) | 0 |

| Subgroup 2 | 7 (35.0) | 3 (15.0) | 3 (15.0) | 4 (20.0) | 3 (15.0) |

In summary, in the first scenario, while the approach of the participants from the first subgroup seeks to actively confront and resolve the conflict, the second subgroup avoids direct confrontation. This difference in approaches would suggest that the first subgroup tends to seek intermediate solutions and maintain open communication to resolve conflicts, while the second subgroup may show a tendency to avoid direct confrontation and to ignore or minimize problems instead of addressing them adequately.

The comparison between subgroups in the second scenario, which concerns a disruption caused by two students refusing to comply with the rules, shows that a higher proportion of participants in the predominantly assertive subgroup 1 opted for reactive-type strategies, such as Domination and Compromise. In contrast, in subgroup 2, a higher frequency of implementation of proactive strategies, such as the Collaborative type, is observed. In addition, in this subgroup the use of Avoidance is observed, a strategy that is not recorded in the more assertive subgroup (details available in Table 2). Below are quotes to illustrate how conflict was managed in the second scenario by both subgroups.

Scenario 2: In previous classes, two students sat together and talked constantly. At the beginning of the current class, they were asked to sit apart, but refused to do so.

Quote 1 (Domination, Subgroup 1, Visual Arts) What are you girls doing together? I told you to sit apart because you talk a lot and distract the rest of the group. This can't happen, because we have only an hour for the class and you make us waste half an hour with your distractions. So, come on, Karen, you're going to sit there on the right, behind Pablo. You can't be with Rosa because the two of you together are a very bad influence, you wind each other up. [D03_1:39-2:37, P9]

Quote 2 (Compromise, Subgroup 1, History): Antonio and Bruno, I asked you to sit apart, why didn't you do so? You should respect my directions. In future activities you can sit together, but now you need to follow the instructions for the activity to work. [D19_1:39-2:40, P7]

Quote 3 (Collaboration, Subgroup 2, Languages): I would like to know why you are sitting together. It would be better if you sat separately, as I suggested earlier. [D41_0:39-1:16, P32]

The first two quotes, which illustrate the profile of the first subgroup, show a directive approach by the teacher. The teacher sets clear rules and specific instructions for students, seeking to minimise distractions and maintain order in the learning environment. On the other hand, the third quote, which illustrates the profile of the second subgroup, highlights a collaborative approach. Here, the teacher strives to understand the motivations behind the students' actions, promoting collaboration.

| Avoidance | Accommodation | Domination | Compromise | Collaboration | |

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | |

| Subgroup 1 | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 9 (47.4) | 9 (47.4) | 0 |

| Subgroup 2 | 4 (20.0) | 2 (10.0) | 5 (25.0) | 5 (25.) | 6 (30.0) |

In the analysis of the second scenario conflict, the teacher's directive approach in the first quotes reflects a more traditional strategy, focused on controlling the situation. In contrast, the collaborative approach in the third quote suggests a more contemporary approach, geared towards joint problem-solving.

In the third scenario (conflicts during group work) subgroup 1 shows a higher percentage of implementation of the Domination strategy compared to subgroup 2 (68.4% and 20%, respectively). Furthermore, none of the participants in subgroup 1 avoided managing conflict, while those in subgroup 2 mostly opted for Avoidance (see details in Table 3).

The following quotes illustrate the profile of both groups during the management of the simulated conflict in the third scenario.

Scenario 3: During a group activity, a student stands up and walks away from the group, refusing to participate.

Quote 1 (Domination, Subgroup 1, History): "Antonio, why are you getting up? Do you want to do the activity by yourself? Do you want to interpret what the French Revolution was all about all by yourself? Go ahead! Now that you're up, if you want, it can be all yours. I'll wait for you here. I'll wait here until you do something. If not, sit down again and we'll do it as a group (Antonio doesn't react). But OK, if you want to volunteer, go ahead! Come on, go on! I'll help you if you want. Don’t you have anything to say, Antonio? Come on, go on, go and sit down; otherwise, as I said, the damn class has to go on, OK? So, if you want, you can stay there and pretend you are a tree, which is another option." [D19.1:30_2:40, P7]

Quote 2 (Avoidance, Subgroup 2, Visual Arts): "Well, Karen wants to work alone. We are going to split into three groups. One with four people, one with three and one with just Karen. Karen will be the first to present. You'll have a little less time to do your work, Karen. Are you sure you don't want to join the rest of your classmates? (Karen doesn't answer) No? OK, Karen has decided to do it alone. That's it then. OK, guys, let's get to work. If you have any questions, you can come to my desk and ask me." [D3.2:44-3:52, P9]

| Avoidance | Accommodation | Domination | Compromise | Collaboration | ||

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | ||

| Subgroup 1 | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 13 (68.4) | 5 (26.3) | 0 | |

| Subgroup 2 | 8 (40.0) | 3 (15.0) | 4 (20.0) | 0 | 5 (25.0) |

The quotes in the third scenario illustrate two different approaches to dealing with group conflicts. The first one illustrates an authoritarian approach by the teacher, challenging the student to complete the activity alone. In contrast, the second shows an avoidance approach by the teacher, allowing the student to work alone without addressing the conflict directly. This suggests that teachers adopt different conflict management strategies: some based on control and others on avoiding direct confrontations. Although avoidance does not always ensure harmony, it may prevent conflict escalation or maintain classroom dynamics.

In conclusion, the contrast between subgroups 1 and 2 in terms of conflict management suggests that teachers choose strategies according to their teaching style, educational philosophy and ability to adapt to students' needs. Subgroup 1 seems to lean toward a more directive and authoritarian approach, which may reflect a preference for maintaining tight control over student behaviour to ensure an orderly and disciplined learning environment. In contrast, subgroup 2 shows a tendency toward more flexible and adaptive strategies, suggesting a willingness to negotiate and compromise with students to avoid confrontation and foster a more collaborative atmosphere.

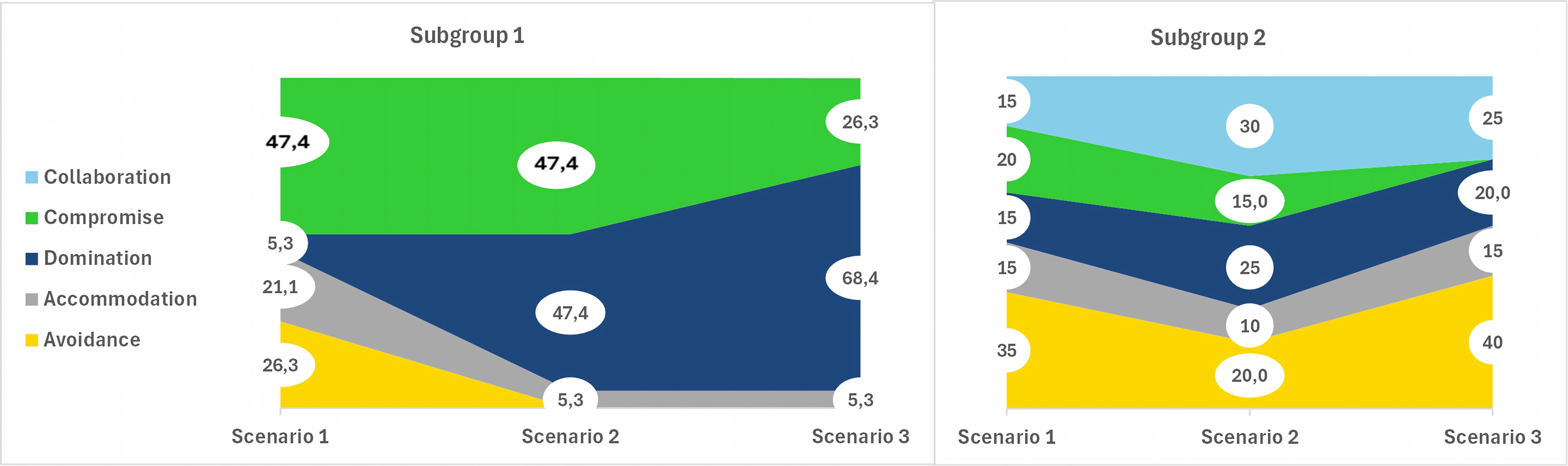

Behaviour of the strategies in the different scenarios

Figure 3 describes the various strategies implemented in the three communicative scenarios simulated in the VR experience, based on the results of the descriptive statistics. The Domination strategy shows a considerable increase, surpassing the Compromise and Avoidance strategies, which predominated in both subgroups in the first scenario. This upward trend is noticeable in subgroup 1 (S1: 5.6%, S2: 50.0%, S3: 68.4%).

In the second scenario, this pattern intensifies, with subgroup 1 adopting more assertive strategies, such as Domination and Compromise. In contrast, participants in subgroup 2 used more Collaboration, a strategy not implemented by subgroup 1 throughout the experience. The Avoidance strategy was prominently present in the first scenario for both subgroups. However, its frequency of implementation is higher in the later scenarios among participants in subgroup 2 (S1: 33.3, S2: 19.0%, S3: 42.9%), while no participant from subgroup 1 used it in the later scenarios. In addition, there were no notable changes in the use of the Accommodation strategy, which was used less frequently during the experience.

Evolution of the implementation of different strategies during the experience

Note: Values are shown in percentages and reflect the use of various strategies in each scenario (S). S1: Disruptive situations in the teacher-student relationship; S2: Disruptive situations among classmates; S3: Disruptive situations during group work.

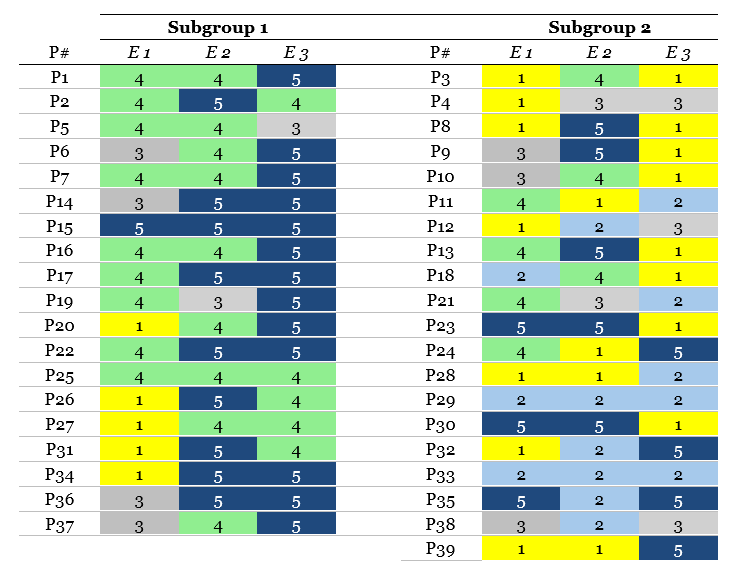

The individual results of the participants in relation to the conflict management strategies used in the simulated scenarios are presented below. Table 4 shows the frequency of use of each strategy. This approach facilitates a deeper understanding of the skills and preferences of participants in both subgroups.

Note: The numbers indicate the type of strategy implemented by each participant (P) in the various scenarios (S) simulated. They correspond to (1) Avoidance, (2) Collaboration, (3) Accommodation, (4) Compromise and (5) Domination. The colours match the legend used to identify the strategies. Subgroup 1: predominantly assertive-uncooperative (n=19); subgroup 2: predominantly avoidant, low assertiveness-moderate cooperation (n=20).

In Subgroup 1 (Assertive-Non-Cooperative), the high frequency of the Domination strategy (40.4%) indicates that, although there is a willingness to negotiate and compromise, authoritarian tactics are used to resolve conflicts. In Subgroup 2 (Avoidant, Low Assertiveness-Moderate Cooperation), a high proportion of Avoidance (31.7%) and a combination of other strategies are observed, showing a tendency to avoid conflict and adopt a less proactive approach.

Among the 39 participants, 20 (51.3%) use Avoidance in one of the scenarios, and this is the second most common strategy after Domination (25 participants, 64.1%). Avoidance is associated with a lower level of CMC. In contrast, five participants (12.8%) use Collaboration, which involves high assertiveness and cooperation and 11 (28.2%) use Compromise which combines medium levels of both dimensions. These 16 participants (40%) demonstrate an acceptable level of CMC due to their ability to manage conflicts in a more constructive and cooperative manner.

After a thorough analysis of the partial results, it is worth highlighting the main findings that shed light on how participants approached and resolved conflicts in various scenarios.

- It was observed that participants mostly employed Domination and Compromise strategies, although the significant presence of the Avoidance strategy was also highlighted.

- Differences were evidenced in the implementation of strategies in the three simulated communicative scenarios.

- Two distinctive profiles were identified among the participants: one characterized by being assertive, but not cooperative, and another with low assertiveness, but moderate cooperation.

Overall, these findings provide a clear picture of how participants manage conflict and underscore the importance of understanding behavioural patterns in the communicative context.

DISCUSSION

The main objective of our research was to analyse the CMC of pre-service teachers by identifying the coping strategies they adopt in three specific scenarios within an IVRE. These scenarios include disruptive situations affecting the teacher-student relationship, interactions between classmates, and conflicts during group work.

First, it was observed that participants tended to employ Domination and Compromise strategies, focused on imposing discipline (Canter & Canter, 2001). While these strategies may be effective in the short term, they do not address the underlying causes of disruptions (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008; Martinez et al., 2020; Payne, 2015). These findings align with those of Tarantul and Berkovich (2024), who suggested that secondary school teachers often resort to reactive strategies, which may be less effective than proactive ones in emotionally regulating conflict.

Assertiveness implies acting with determination and establishing clear limits, and this is a fundamental communicative skill for teachers (Iglesias-Díaz & Romero-Pérez, 2021; Inbar-Furst et al., 2021). However, according to evidence gathered from various quotes, many participants in this experience did not show empathy, as recommended by the scientific literature (Keller & Becker, 2020; McGrath & Van Bergen, 2019). On the contrary, on certain occasions, some participants chose to use public criticism, warnings and even threats accompanied by humiliating speeches. These actions may lead to an escalation in conflict, without effectively contributing to regulating behaviour, which hinders the creation of an environment conducive to respect and collaboration in the classroom (Campbell, 2004; Davis, 2017).

Strategies aimed at anticipating or modifying emotional states (anticipatory, proactive approach) involve actions such as consciously choosing circumstances to influence the anticipated emotional outcome, actively modifying situations to alter their emotional effect, directing attention to specific aspects to influence emotions, and cognitively changing the interpretation of a situation to generate a different emotional response (Gross, 2015). These strategies, which align with Compromise and Collaboration and seek to promote effective emotion management and prevent the occurrence of unwanted emotions, were less used by participants in this study.

Secondly, our findings suggest that the selection of strategies to confront classroom conflicts may vary according to the communicative context and interpersonal dynamics (Luhmann, 1982). In the first scenario, referring to the teacher-student relationship, Compromise and Avoidance strategies predominated. Although the participants showed willingness to address problems, they also manifested a certain reluctance to face conflictive situations. This dynamic resulted in a restrained performance, where conflict intervention was balanced with prudence, evoking the concept of 'uneasy peace' described by Payne (2015), which seeks to maintain a delicate balance between control and empathy towards students.

In the second scenario, involving interactions between classmates, participants adopted a different stance, turning the classroom into a space of negotiation and social tensions. A combination of Domination and Compromise strategies was identified, with some participants seeking to exert control while others were willing to collaborate. The latter strategy is the most recommended for maintaining a positive learning environment and addressing underlying causes of classroom behaviour ( Alasmari & Althaqafi, 2021; Evertson & Weinstein, 2013; Govorova et al., 2020).

In the third scenario, focused on conflicts during group work, the Domination strategy was more evident. Participants adopted an authoritarian stance, seeking to impose their will to resolve the conflict and directing their intervention toward the student who was perceived as the cause of the problem. This exacerbated power and leadership dynamics, reflecting boundary-setting approaches to behaviour management that rely on the implicit power imbalance between teachers and students, a concept that Canter and Canter (2001) capture in their use of the term "assertive discipline."

Overall, our findings support the conclusions of Ceballos-Vacas and Rodriguez-Ruiz (2023) on the prevalence of dominant and avoidant styles in conflict management by secondary school teachers in Spain. The presence of verbal or emotional violence as a recurrent response reflects the persistent application of punitive approaches in Spanish secondary education, as highlighted by Buendía-Eisman et al. (2015).

The results of this study confirm the findings of Zurlo et al. (2020), showing that teachers with a Multi-strategic and Engaged pattern in conflict management use a wide range of strategies, similar to subgroup 2 of this study. However, the high frequency of the Avoidance strategy (31.7%) in this subgroup suggests a tendency to avoid conflict, possibly due to lack of confidence or preference for avoiding the discomfort of confrontation (Tarantul & Berkovich, 2024). In Subgroup 1 (Assertive-Non-Cooperative), the high frequency of Domination (40.4%) indicates a tendency toward authoritarian strategies, possibly due to the need for quick decisions, maintaining control in the classroom (Sabornie & Espelage, 2023) or difficulty reaching compromises (Thomas & Kilmann, 2008).

The study also suggests that participants adopt diverse approaches to managing conflict, with notable variations in assertiveness and cooperation (Emmer & Stough, 2003). This variability underscores the importance of understanding and addressing individual differences in coping strategies to promote effective conflict management in the classroom and other educational contexts.

Unlike other studies based on self-references to assess CMC, the IVRE experience made it possible for trainee teachers to face conflict in a realistic communicative situation, generating the need for immediate action. This challenged participants to make decisions to adjust their performance and manage conflict, thus simulating the ecological environment of the classroom. This approach is aligned with our conceptual framework regarding teacher training for classroom management ( Doyle, 2006; Evertson & Poole, 2012). The results corroborate the validity of the Didascalia VC platform for this purpose and highlight its potential in terms of realism (Ke et al., 2020) and its ability to simulate complex and challenging situations, such as the management of disruptive behaviour in the classroom.

CONCLUSIONS

By exploring the potential of the IVRE to analyse CMC, the coping strategies used by participants were identified, representing a significant contribution to knowledge about classroom management by providing an effective tool to explore this competency. The methodology employed confirmed the usefulness of a personalized, safe and playful environment to capture experiential aspects that reflect communicative relationships in the classroom. This study highlighted two crucial aspects that other methodologies fail to capture in the assessment of CMC:

- 1. Distinctive profiles: Two distinctive profiles were identified among the participants: one characterized by an assertive but non-cooperative attitude, and another with low assertiveness and moderate cooperation. This provides a contextualized view of both proactive and reactive management strategies in a simulated educational environment.

- 2. Influence of the communicative context: The differences observed in the strategies implemented in the three simulated scenarios suggest that the nature of the communicative situation may influence the decisions participants make to manage perceived conflicts.

This study provides a valuable insight for teacher training in classroom management by highlighting the importance of experiential learning. Empowering teachers with proven tools and approaches enables them to deal effectively with conflict and foster constructive relationships with students, thereby improving the quality of education and emotional well-being.

Compared to previous studies on Didascalia VC, this work makes significant advances. While Álvarez et al. (2023) focused on reflection and self-efficacy in classroom management in IVRE, and Álvarez et al. (2024) explored the usability of the platform and its impact on technology adoption, this study more precisely assesses classroom conflict management skills using IVR.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the study, such as sample size and lack of diversity, which restrict the generalizability of the results. In addition, the simulated environment may not fully reflect actual classroom dynamics.

For future research, it is recommended that the study be replicated in real educational settings to assess the external validity of the results and to explore the impact of additional variables such as gender, socioeconomic level of the student body and other contextual particularities. A notable limitation is the lack of participant and expert feedback, which could have enriched and validated the findings. Without this feedback, the assessment of the CMC may be less accurate and relevant. Incorporating feedback in future studies would improve the validity and applicability of the findings. In addition, the use of learning analytics could enrich the assessment and development of CMC, allowing to analyse behavioural patterns and provide personalized recommendations, as well as detailed information on student progress to adapt pedagogical approaches more effectively.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities [Grant number: PDC2022-133582-I00]. The researchers express their sincere thanks to the trainee teachers who have voluntarily participated in this study.

REFERENCES

Alasmari, N. J., & Althaqafi, A. S. A. (2021). Teachers’ practices of proactive and reactive classroom management strategies and the relationship to their self-efficacy. Language Teaching Research.https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211046351

Álvarez, I. M., Manero, B., Morodo, A., Suñé-Soler, N., & Henao, C. (2023). Immersive Virtual Reality to improve competence to manage classroom climate in secondary schools. Educación XX1, 26(1), 249-272. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.33418

Álvarez, I. M., Manero, B., Romero-Hernández, A., Cárdenas, M., & Masó, I. (2024). Virtual reality platform for teacher training on classroom climate management: evaluating user acceptance. Virtual Reality, 28(2), 78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-024-00973-6

Bingham, S. G., Carlson, R. E., Dwyer, K. K., & Prisbell, M. (2009). Student misbehaviors, instructor responses, and connected classroom climate: Implications for the basic course. Basic Communication Course Annual, 21(7), 30-68. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/bcca/vol21/iss1/7

Bocos-Corredor, M., López-García, A., & Díaz-Nieto, A. (2020). Classroom VR: a VR game to improve communication skills in secondary school teachers. [Final Degree Project]. E-Prints Complutense. https://doi.org/10.21125/edulearn.2020.2148

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69909-7_3470-2

Buendía-Eisman, L., Expósito-López, J., Aguadez-Ramírez, E.M., & Sánchez- Núñez, C.A. (2015). Analysis of coexistence in multicultural Secondary education classroom. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 33(2), 303-319. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.33.2.211491

Campbell, M. (2004). School victims: An analysis of 'my worst experience in school' scale. In Performing Educational Research: Theories, Methods and Practices (pp. 77-87). https://eprints.qut.edu.au/2293/1/2293.pdf

Canter, L., & Canter, M. (2001). Assertive discipline: Positive behavior management for today’s classroom (3rd ed.). Seal Beach, CA: Canter.

Ceballos-Vacas, E. M., & Rodríguez-Ruiz, B. (2023). How do teachers and pupils actually deal with conflict? An analysis of conflict resolution strategies and goals. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 41(2), 551-572. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.547241

Christofferson, M., & Sullivan, A. L. (2015). Preservice teachers’ classroom management training: A survey of self‐reported training experiences, content coverage, and preparedness. Psychology in the Schools, 52(3), 248-264. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21819

Clunies‐Ross, P., Little, E., & Kienhuis, M. (2008). Self‐reported and actual use of proactive and reactive classroom management strategies and their relationship with teacher stress and student behaviour. Educational Psychology, 28(6), 693-710. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802206700

Cook, C. R., Fiat, A., Larson, M., Daikos, C., Slemrod T., Holland E. A., Thayer A. J., Renshaw T. (2018). Positive greetings at the door: Evaluation of a low-cost, high-yield proactive classroom management strategy. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(3), 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717753831

Davis, J. R. (2017). From discipline to dynamic pedagogy: A re-conceptualization of classroom management. Berkeley Review of Education, 6(2), 129-153. https://doi.org/10.5070/B86110024

Doyle, W. (2006). Ecological approaches to classroom management. In C. M. Evertson & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 97-125). Erlbaum.

Emmer, E. T., & Stough, L. M. (2003). Classroom management: A critical part of educational psychology, with implications for teacher education. In Educational Psychology (pp. 103-112). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3602_5

Evertson, C. M., & Poole, I. R. (2012). Proactive Classroom Management. In 21st Century Education: A Reference Handbook (pp. I-131-I-139). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412964012.n14

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203874783

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2018). Research methods in education. Routledge.

Govorova, E., Benítez, I., & Muñiz, J. (2020). How Schools Affect Student Well-Being: A Cross-Cultural Approach in 35 OECD Countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00431

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Status and prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Hamilton, D., McKechnie, J., Edgerton, E., & Wilson, C. (2021). Immersive virtual reality as a pedagogical tool in education: a systematic literature review of quantitative learning outcomes and experimental design. Journal of Computers in Education, 8(1), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-020-00169-2

Iglesias-Díaz, P., & Romero-Pérez, C. (2021). Aulas afectivas e inclusivas y bienestar adolescente: Una revisión sistemática. Educación XX1, 24(2), 305-350. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.28705

Inbar-Furst, H., Ayvazo, S., Yariv, E., & Aljadeff, E. (2021). Inservice teachers’ self-reported strategies to address behavioral engagement in the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 106, 103466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103466

Ke, F., Pachman, M., & Dai, Z. (2020). Investigating educational affordances of virtual reality for simulation-based teaching training with graduate teaching assistants. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 32(3), 607-627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-020-09249-9

Keller, M. M., & Becker, E. S. (2020). Teachers’ emotions and emotional authenticity: Do they matter to students’ emotional responses in the classroom? Teachers and Teaching, 27(5), 404-422. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1834380

Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Kugurakova, V. V., Golovanova, I. I., Kabardov, M. K., Kosheleva, Y. P., Koroleva, I. G., & Sokolova, N. L. (2023). Scenario approach for training classroom management in virtual reality. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 13(3), e202328. https://doi.org/10.30935/ojcmt/13195

Lugrin, J. L., Latoschik, M. E., Habel, M., Roth, D., Seufert, C., & Grafe, S. (2016). Breaking bad behaviors: A new tool for learning classroom management using virtual reality. Frontiers in ICT, 3, 26. https://doi.org/10.3389/fict.2016.00026

Luhmann, N. (1982). The world society as a social system. International Journal of General Systems, 8, 131-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/03081078208547442

Martínez, M. B., Chacón, J. C., Díaz-Aguado, M. J., Martín, J., & Martínez, R. (2020). Disruptive behavior in compulsory secondary education classrooms: A multi-informant analysis of the perception of teachers and students. Pulso. Revista de Educación, 43, 15-34. https://revistas.cardenalcisneros.es/article/view/4793/5030

Masó, I. (2022). Los conflictos en el aula de secundaria y las competencias comunicativas del profesorado [Conflicts in the secondary classroom and teachers' communicative competencies]. In J. A. Marín, J. C. de la Cruz, S. Pozo, & G. Gómez (Eds.), Investigación e innovación educativa frente a los retos para el desarrollo sostenible (pp. 1383-1398). Dylinson. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2gz3w6t.111

McGarr, O. (2021). The use of virtual simulations in teacher education to develop pre-service teachers’ behavior and classroom management skills: Implications for reflective practice. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(2), 274-286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1733398

McGrath, K. F., & Van Bergen, P. (2019). Attributions and emotional competence: Why some teachers experience close relationships with disruptive students (and others don’t). Teachers and Teaching, 25(3), 334-357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1569511

McGuire, S. N., Meadan, H., & Folkerts, R. (2024). Classroom and behavior management training needs and perceptions: A systematic review of the literature. Child Youth Care Forum, 53, 117-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-023-09750-z

OECD. (2020). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and school leaders as valued professionals. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en

Olafson, L., & Schraw, G. (2006). Teachers’ beliefs and practices within and across domains. International Journal of Educational Research, 45, 71-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.08.005

Payne, R. (2015). Using rewards and sanctions in the classroom: Pupils’ perceptions of their own responses to current behaviour management strategies. Educational Review, 67(4), 483-504. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1008407

Sabornie, E. J., & Espelage, D. L. (Eds.). (2023). Handbook of classroom management. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003275312

Santiago-Rosario, M. R., McIntosh, K., & Whitcomb, S. A. (2023). Examining teachers’ culturally responsive classroom management self-efficacy. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 48(3), 170-176. https://doi.org/10.1177/15345084221118090

Sarceda-Gorgoso, M. C., Santos-González, M. C., & Rego-Agraso, L. (2020). Las competencias docentes en la formación inicial del profesorado de educación secundaria. Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado, 24(3), 401-421. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v24i3.8260

Seufert, C., Oberdörfer, S., Roth, A., Grafe, S., Lugrin, J. L., & Latoschik, M. E. (2022). Classroom management competency enhancement for student teachers using a fully immersive virtual classroom. Computers & Education, 179, 104410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104410

Tarantul, A., & Berkovich, I. (2024). Teachers’ emotion regulation in coping with discipline issues: Differences and similarities between primary and secondary schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 139, 104439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104439

Thomas, K. W., & Kilmann, R. H. (2008). Thomas-Kilmann conflict mode. TKI Profile and Interpretive Report, 1(11). https://lig360.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Conflict-Styles-Assessment.pdf

Wang, H., Hall, N. C., & Taxer, J. L. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of teachers’ emotional labor: A systematic review and meta-analytic investigation. Educational Psychology Review, 31(3), 663-698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09475-3

Zurlo, M. C., Vallone, F., Dell'Aquila, E., & Marocco, D. (2020). Teachers' patterns of management of conflicts with students: A study in five European countries. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 16(1), 112-127. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i1.1955

Notes

Reception: 01 June 2024

Accepted: 16 July 2024

OnlineFirst: 16 September 2024

Publication: 01 January 2025