Estudios e investigaciones / Research and Case Studies

Connected outside, disconnected inside. Social Networks in initial teacher training

Conectados fuera, desconectados dentro. Las redes sociales en la formación inicial docente

Connected outside, disconnected inside. Social Networks in initial teacher training

RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, vol. 28, núm. 1, 2025

Asociación Iberoamericana de Educación Superior a Distancia

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional.

How to cite: Marcelo-Martínez, P., Yot-Domínguez, C., & Yanes Cabrera, C. (2025). Connected outside, disconnected inside. Social Networks in initial teacher training. [Conectados fuera, desconectados

dentro. Las redes sociales en la formación inicial docente]. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.28.1.41343

Abstract: Social networks have recently become a key space where teachers share information, exchange resources and materials, and engage in relationships, collaboration, and community building. This study aims to investigate whether future teachers use social media for learning and development, identify their reasons for use, and analyze any differences among them. To achieve these objectives, we designed and validated a 33-item questionnaire, which was completed by 231 pre-service teachers in Early Childhood, Primary, and Secondary Education from 10 public and private universities in Spain. The results show that a high percentage of pre-service teachers never use certain social networks like LinkedIn, Facebook, TikTok, or X, while others, such as Instagram and YouTube, are used continuously. Pre-service teachers use social media for three main purposes: finding resources and people for learning, as a medium for academic learning, and as a tool for mutual support. Notable differences were found concerning age and the educational level they are preparing for, with younger undergraduates perceiving the benefits more positively than older master's students. Our study concludes by highlighting the need to integrate the knowledge and use of social media as valuable tools for connected teachers of the 21st century into initial teacher training programs.

Keywords: social networks, teacher training, autonomous learning, educational communication, digital tools.

Resumen: Las redes sociales se han convertido recientemente en espacios privilegiados en los que los docentes comparten información e intercambian recursos y materiales, así como se relacionan, colaboran y crean comunidad. En este artículo nos ha interesado conocer si los futuros profesores utilizan las redes sociales para su aprendizaje y desarrollo, identificar los motivos para su uso y analizar posibles diferencias en ellos. Para responder a estos objetivos, diseñamos y validamos un cuestionario de 33 ítems que fue respondido por 231 profesores en formación de Educación Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria matriculados en 10 centros de estudios universitarios o universidades españolas públicas y privadas. Los resultados evidencian que hay redes sociales que los docentes en formación dicen no utilizar nunca en un porcentaje alto como Linkedin, Facebook, TikTok o X (Twitter), mientras que otras redes sociales como Instagram o YouTube son utilizadas de forma continua. Los docentes en formación utilizan las redes con tres objetivos principales: encontrar recursos y personas para aprender, como medio para su aprendizaje académico y como herramienta para obtener apoyo mutuo. Encontramos diferencias destacables en relación con la edad y el nivel educativo para el cual se preparan, siendo los docentes jóvenes que cursan un Grado quienes perciben más positivamente los motivos que aquellos con mayor edad que estudian un Máster. Se concluye destacando la necesidad de integrar en los programas de formación inicial docente el conocimiento y uso de las redes sociales como herramientas útiles para los docentes conectados del siglo XXI.

Palabras clave: redes sociales, formación de profesores, aprendizaje autónomo, comunicación educativa, herramientas digitales.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, social networks have become spaces in which teachers share information and exchange resources and materials, engage in relationships, collaborate and create a community. We know that social networks weren’t born explicitly for promoting learning and professional teacher development, however, research shows their ability to promote connections and relationships between teaching professionals, as well as allowing them to share their teaching practices ( Tess, 2013 ). That is why, in the field of education, there is growing interest in analyzing how and why teachers use social networks (Carpenter & Kruta, 2014; Carpenter et al., 2020; Marcelo-Martínez et al., 2023; Goodyear et al., 2019; Higueras-Rodríguez et al., 2020).

Social networks are being used massively by the younger population. The last report from the Pew Research Center (Anderson et al., 2023) highlighted that, in 2023, the social networks used most by the young population in the USA were TikTok, YouTube, Instagram and Snapchat. In Spain, the Estudio de Redes Sociales (Social Network Study) (IAB, Spain, 2023) shows that 94% of young people between 18 and 24 years use social networks, and their use is slightly higher among women. Furthermore, it indicates that the youngest part of the population prefers TikTok, while those 18 and above opt for Instagram, WhatsApp and YouTube. These social networks are characterized by image-based and video-based content, using tools for quick interaction and allowing content production in a simple way (Alhabash & Ma, 2017).

In this study, we examine whether pre-service teachers also use social networks in their process of learning and teaching. Recent studies have demonstrated the power of social networks, such as TikTok, as didactic platforms (Carpenter et al., 2024; Flores-González et al., 2022; Huebner, 2022) or Instagram as a tool to promote student involvement (Reyna, 2021; Ruiz-Ruiz & Izaguirre, 2022). These have some vernacular features that make them interesting resources in initial teacher training, for example: allowing real-time interaction with and among students, giving opportunities to provide immediate feedback any time, any place or facilitating learning through different voices and points of view (Lemon & O’Brien, 2019). However, there are very few teacher trainers who make use of social networks to promote new spaces where students can interact and carry out their activities (Carpenter & Green, 2018). This is not a new phenomenon in the field of education: changes and innovations in communication and learning processes emerge first in spaces external to the training institution. In this situation, pre-service teachers perceive what Feiman-Nemser and Buchman (1988) called the “lagoon of two worlds”: the university world and the external real world of school or life.

It is true that, when social networks have been used in initial teacher training, their use has not always been represented as a positive factor in relation to pre-service teachers’ learning ( Greenhow & Askari, 2017). Sometimes, students feel overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of information received through them (Carpenter et al., 2017) or they find it difficult to separate the use of social networks for personal or professional reasons, referred to as “context collapse” (Marwick & Boyd, 2011; Iredale et al., 2020; Lemon & O'Brien, 2019; Mullins & Hicks, 2019). However, the use of social networks, such as X, in initial teacher training also has positive aspects (Carpenter et al., 2023). According to Hyndman and Harvey (2020), access to X provides pre-service teachers with a higher degree of autonomy in information search processes for their academic activities. Moreover, the use of social networks contributes to the identity development of future teachers, allowing them to construct and manage their identities through interaction with colleagues and experts (Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2014b).

Thus, the reactions of pre-service teachers towards the use of social networks in their training programs can vary. Interaction with social networks can also have different dimensions depending on the characteristics of the subjects themselves, based on their interests, motivation or confidence in social networks (Hamedinasab et al., 2023). Teachers are not a unique group regarding the use of social networks. Some studies have analyzed differences according to variables such as sex, age or educational level, collecting different results. Regarding sex, Martín-Gutiérrez at al. (2024) found that women have a more favorable perception of the usefulness of social networks. Casipit et al. (2002) concluded that women use social networks for their work more frequently than men. However, Karimi et al. (2022) didn’t find significant differences between the sexes in the use of Pinterest, although men focus more on content selection and women explore non-educational content. Patahuddin et al. (2022) obtained similar results with Facebook.

Fewer studies have been conducted on trying to understand the differences based on the age of the teachers. In a previous study (Marcelo-Martínez et al., 2024), the differences between pre-service, new and experienced teachers were analyzed in terms of their reasons for using social networks and the roles they assume on them. They found that, while pre-service and new teachers used social networks to access materials and resources for their own learning, assuming the role of a passive observer, more experienced teachers started to participate more actively on social networks, looking for specific resources, establishing contact with other teachers, contributing their own educational materials and helping other teachers with their questions, or even forming their own communities. In the case of Pinterest, Schroeder et al., (2019) found that pre-service teachers dedicated more time to searching for motivating materials than experienced teachers, a difference marked by a lack of time, according to the authors.

We consider that there is still a lack of information related to not only the level of social network use by pre-service teachers, but also the way they use them and the impact that these networks have in the learning and teaching processes of new teachers (Kennedy, 2019). The purpose of this research is to investigate the use that Spanish pre-service teachers make of social networks in their training process and to analyze the reasons for their use both in their formal learning in the training program and in their informal learning as future teachers. Therefore, we establish the following research questions:

- 1. What is the level of use that pre-service teachers make of social networks?

- 2. What are the reasons why future teachers use social networks?

- 3. Are there differences in the reasons for use based on gender, age or the educational level for which pre-service teachers are preparing to teach?

METHODOLOGY

For this study, we designed and distributed a digital questionnaire which allowed us to collect data which responded to the questions posed. The questionnaire was comprised of open and closed questions, collecting information about the participants (sex, age, university, degree) and their use of social networks (frequency, when they started using them, profiles followed). Moreover, it included a 33-item scale to identify the reasons for using social networks. The scale was based on previous studies on the use of Twitter by teachers and learning through social networks (Staudt Willet, 2019; Nochumson, 2018, 2020; Higueras-Rodríguez et al., 2020; Gilbert, 2016; Greenhow & Askari, 2017; Li et al., 2020; Marcelo-Martínez et al., 2023). The items were evaluated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot).

To validate the scale, principal component analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis were used with JASP software (v0.11.1.0). The KMO index was 0.939, exceeding the recommended value of 0.6, and Bartlett's test of sphericity had a critical level of 0.000. Cronbach's alpha of the scale was 0.959 and McDonald's ω was 0.957. The total correlation of items was not less than 3 (Table 1). Exploratory factor analysis with promax rotation extracted a three-factor model, with a Chi-square distribution of < 0.001, coincident with the principal component analysis. The load of the items was always superior to 0.3. The model was confirmed by confirmatory factor analysis, showing a good fit with a Chi-square test p-value of < 0.001, TLI of 0.927, RMSEA 90%, CI lower bound of 0.049, and GFI of 0.927. The Cronbach’s alpha of each factor was: 0.931, 0.910 and 0.914; and the McDonald's ω was: 0.929, 0.911 and 0.914.

The first factor, “Finding resources and people to learn from” (PC1), highlights the usefulness of social networks for pre-service teachers to find content, resources and materials, as well as to connect with other teachers. The second factor (PC2), “Academic learning”, refers to the use of networks to prepare subjects, interact, work together, exchange doubts and receive feedback from trainers, consolidating a learning network. The third factor (PC3), “Mutual support”, includes motives that show how social networks offer open and positive spaces to avoid possible teacher isolation, to talk, ask for support and get help.

| PC | Item | If item dropped | Item-rest correlation | Component Loading | |

| McDonald's ω | Cronbach's α | ||||

| 1 | 1. Get to know teachers who share interesting materials and content for my training | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.553 | 0.790 |

| 2. Find educational resources shared by teachers | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.542 | 0.905 | |

| 4. Find examples of programs or activities to use in practice | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.514 | 0.669 | |

| 5. Know the opinions of other teachers on current educational topics | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.644 | 0.685 | |

| 13. Learn from the materials created by other teachers | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.527 | 0.877 | |

| 14. Find the way to improve my teaching skills to ensure good future performance | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.721 | 0.802 | |

| 16. Detect my own weaknesses and training needs | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.657 | 0.616 | |

| 19. Apply ideas or methods that I’ve learnt on social networks in my teaching practice | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.643 | 0.597 | |

| 20. Learn about topics that I know less about | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.629 | 0.708 | |

| 23. Feel like I form part of a wider teacher community | 0.955 | 0.957 | 0.720 | 0.356 | |

| 25. Reflect on my own experiences as a future teacher | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.681 | 0.586 | |

| 29. Find other teachers or students with similar worries to mine | 0.955 | 0.957 | 0.763 | 0.446 | |

| 33. Find people who choose and distribute educational content | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.572 | 0.807 | |

| 2 | 11. Collaborate with other students on a shared project | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.528 | 0.470 |

| 21. Prepare an exam or class project | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.481 | 0.636 | |

| 22. Interact with my colleagues or with the community in an activity organized by teachers | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.564 | 0.846 | |

| 24. Receive feedback from my professors | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.561 | 0.760 | |

| 26. Develop my own presence on the network as a teacher | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.705 | 0.636 | |

| 27. Receive immediate feedback from other colleagues and teachers | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.623 | 0.847 | |

| 28. Start creating my own network of people with whom I have common interests | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.663 | 0.562 | |

| 30. Access a safe place where I can solve my doubts as a future teacher | 0.955 | 0.957 | 0.735 | 0.526 | |

| 31. Carry out an activity planned by a professor from my degree/master’s | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.569 | 0.832 | |

| 32. Share materials or resources that I have designed with others | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.636 | 0.775 | |

| 3 | 3. Ask other teachers questions about my doubts | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.617 | 0.535 |

| 6. Ask for help from teachers to solve a problem I have as a pre-service teacher | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.600 | 0.639 | |

| 7. Feel like I am in contact with other practicing teachers | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.685 | 0.696 | |

| 8. Share my own emotions and concerns with others | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.660 | 0.880 | |

| 9. Create professional awareness and not become an isolated future teacher | 0.955 | 0.957 | 0.696 | 0.695 | |

| 10. Know that other students have the same problems as me | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.666 | 0.532 | |

| 12. Have conversations about education with other teachers | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.652 | 0.752 | |

| 15. Talk about important topics related to education in the current world | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.675 | 0.686 | |

| 17. Get help when I try to implement a teaching resource or strategy | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.577 | 0.371 | |

| 18. Participate in a space that I consider to be open and positive | 0.955 | 0.957 | 0.718 | 0.574 | |

The questionnaire ended with a 5-item scale which asked participants to rate, from 1 to 4 (1 being never and 4 constantly), to what extent the use of social networks and their application in the educational field had been part of their initial teacher training.

SUBJECTS

The questionnaire was distributed via email to students enrolled in 10 public and private Spanish universities in degrees related to the teaching profession. Sampling was non-probabilistic and incidental. A total of 231 pre-service teachers participated in the first phase of the research, 77.4% were women and 22% were men. Their ages oscillated between 18 and 57 years, with the majority being between 18 and 25 years old (65.8%). The average age was 25.65 years. In terms of the universities, 62 study at the Autonomous University of Madrid, 25 at the University of Seville, 49 at the University of Burgos, 14 at the CEU Andalusia, 11 at the University of Granada, 9 at the University of Málaga, 3 at the Complutense University of Madrid, 3 at the Francisco de Vitoria University and 5 at other universities. A total of 57.6% are studying an undergraduate degree and 31.8% a master’s degree. They are studying to work at different educational levels: 22.1% in Pre-School Education, 35.5% Primary Education, 26.8% Secondary Education, 4.8% Baccalaureate and 10.4% Vocational Training.

DATA ANALYSIS

The quantitative data obtained from the questionnaire were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis and non-parametric analysis for comparing means in independent groups (Mann Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate). To determine the hypothesis test, we assumed a significance level of less than 0.01. The independent variables were sex, age (with 4 ranges: 20 or under, 21-15 years old, 26-30 years old and 31 years old or more) and the level of studies for which they are preparing: Degree in Early Childhood Education and Primary Education and Master's Degree in Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate, Vocational Training and Language Teaching. If differences were found, pairwise comparisons and cross-tabulations were made. IBM SPSS v.29 was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

Level of use of social networks by pre-service teachers

The first objective of this research was to find out whether pre-service teachers use social networks, which ones they use and how often they use them. The results show that there are some social networks that a high percentage of pre-service teachers say they never use, such as LinkedIn (66.8%) and Facebook (57.3%), followed by TikTok (42.7%) and X (37.9%) (Table 2). Instagram is the network used most by pre-service teachers (55.6%), followed by YouTube (42.2%). Of note is the case of TikTok, which receives polarized attention from respondents. Some 42.7% say they never use it, but, on the contrary, 25.6% use it continuously. These differences may be determined by variations in the perception of the educational usefulness of TikTok. They certainly suggest the need to explore how this social network has been integrated as a resource by some pre-service teachers so that we can maximize its educational potential and address concerns that may generate resistance.

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Constantly | |

| X (previously Twitter) | 37.9% | 28.2% | 17.5% | 16.5% |

| 57.3% | 23.1% | 11.1% | 8.5% | |

| 34% | 25.5% | 25.5% | 15.5% | |

| 11.2% | 12.2% | 21% | 55.6% | |

| 66.8% | 20.4% | 11.2% | 1.5% | |

| TikTok | 42.7% | 15.1% | 16.6% | 25.6% |

| YouTube | 2.8% | 14.2% | 40.8% | 42.2% |

Pre-service teachers use social networks in a stable manner over time. A total of 36.8% of teachers have been using them for more than seven years and 36.4% for between four and seven years. The use of social networks begins before access to university and training studies as future teachers. Most of the participants started using social networks on their own initiative (58.9%), 25.5% on the recommendation of a classmate/friend and 3% said they started as a result of their university studies, having been invited to do so in one of their subjects.

Pre-service teachers’ reasons for using social networks

The second objective is to analyze the reasons for the use of social networks by pre-service teachers. If there is one thing that stands out in the use of social networks, it is the possibilities they offer to promote informal learning spaces through the observation of videos, participation in online activities or the search for and exchange of educational resources, as well as to facilitate what has come to be known as “networking”. Thus, for pre-service teachers, social networks are understood mainly as a space in which to interact with both digital and personal resources, as part of a personal learning network.

There are three main groups of motives that move pre-service teachers to use social networks as part of their academic and professional work. These motivations are closely connected to the three factors described above. The first is related to using social networks as a means to “find resources and people to learn from” (PC1). Future teachers use social networks to find other teachers and learn from the materials or programs they produce and share on topics they are less familiar with or by participating in events and seminars. A second set of motives alludes to “academic learning” (PC2), namely the use that pre-service teachers make of the networks mediated by their trainers in relation to activities and processes of communication and collaboration through social networks throughout their academic life. Finally, the third group of motives is related to the use of social networks as “mutual support” in social and emotional aspects (PC3). These reasons are related to sharing emotions in these spaces and feeling in tune with other peers, using them to overcome isolation or to raise doubts and queries. The mean values of this last set of items are significantly lower than those of the first group, which leads us to think that, for pre-service teachers, social networks are not the ideal space for establishing deep links with other people (Table 3).

| ITEMS | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Standard deviation |

| 1. Get to know teachers who share interesting materials and content for my training | 1 | 5 | 3.6 | 1.28 |

| 2. Find educational resources shared by teachers | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1.11 |

| 3. Ask other teachers questions about my doubts | 1 | 5 | 2.65 | 1.31 |

| 4. Find examples of programs or activities to use in practice | 1 | 5 | 3.48 | 1.27 |

| 5. Know the opinions of other teachers on current educational topics | 1 | 5 | 3.42 | 1.26 |

| 6. Ask for help from teachers to solve a problem I have as a pre-service teacher | 1 | 5 | 2.23 | 1.26 |

| 7. Feel like I am in contact with other practicing teachers | 1 | 5 | 2.96 | 1.41 |

| 8. Share my own emotions and concerns with others | 1 | 5 | 2.33 | 1.36 |

| 9. Overcome the isolation that I often feel among my colleagues | 1 | 5 | 3.02 | 1.37 |

| 10. Know that other students have the same problems as me | 1 | 5 | 3.07 | 1.35 |

| 11. Collaborate with other students on a shared project | 1 | 5 | 2.46 | 1.39 |

| 12. Have conversations about education with other teachers | 1 | 5 | 2.27 | 1.26 |

| 13. Learn from the materials created by other teachers | 1 | 5 | 3.9 | 1.13 |

| 14. Participate in seminars and open training activities online | 1 | 5 | 3.73 | 1.14 |

| 15. Talk about important topics related to education in the current world | 1 | 5 | 2.68 | 1.36 |

| 16. Detect my own weaknesses and training needs | 1 | 5 | 3.45 | 1.21 |

| 17. Get help when I try to implement a teaching resource or strategy | 1 | 5 | 3.02 | 1.32 |

| 18. Participate in a space that I consider to be open and positive | 1 | 5 | 3.08 | 1.44 |

| 19. Apply ideas or methods that I’ve learnt on social networks in my teaching practice | 1 | 5 | 3.56 | 1.27 |

| 20. Learn about topics that I know less about | 1 | 5 | 3.88 | 1.12 |

| 21. Prepare an exam or class project | 1 | 5 | 3.22 | 1.22 |

| 22. Interact with my colleagues or with the community in an activity organized by teachers | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1.35 |

| 23. Feel like I form part of a wider teacher community | 1 | 5 | 3.26 | 1.33 |

| 24. Receive feedback from my professors | 1 | 5 | 2.47 | 1.32 |

| 25. Reflect on my own experiences as a future teacher | 1 | 5 | 3.37 | 1.28 |

| 26. Develop my own presence on the network as a teacher | 1 | 5 | 2.48 | 1.31 |

| 27. Receive immediate feedback from other colleagues and teachers | 1 | 5 | 2.5 | 1.33 |

| 28. Start creating my own network of people with whom I have common interests | 1 | 5 | 2.61 | 1.38 |

| 29. Find other teachers or students with similar worries to mine | 1 | 5 | 3.12 | 1.30 |

| 30. Access a safe place where I can solve my doubts as a future teacher | 1 | 5 | 2.76 | 1.32 |

| 31. Carry out an activity planned by a professor from my degree/master’s | 1 | 5 | 2.65 | 1.36 |

| 32. Share materials or resources that I have designed with others | 1 | 5 | 2.57 | 1.44 |

| 33. Find people who select and distribute educational content | 1 | 5 | 3.7 | 1.24 |

In the final scale, we see that pre-service teachers find very few reasons to use social networks for their academic learning. They also give little importance to aspects related to their involvement in learning processes, collaboration and communication through social networks. In general, students indicate that they have scarcely been informed about the use of social networks in their learning processes. However, there is variability in their practical application, with the feedback received by teachers through social networks being particularly low. Although there is certain integration of these spaces in the curriculum and a moderated motivation for their future use, it is not consistent nor intensive, suggesting that there is still room for improvement in these areas, as can be seen in Table 4.

| ITEMS | Average | Standard Deviation |

| It has made me aware of the existence and usefulness of social networks as a space to share knowledge | 2.51 | .89 |

| I have learned to use the networks to find out about examples and educational practices related to my subjects | 2.4 | .93 |

| I’ve received feedback from the teachers training me through social networks | 1.97 | .91 |

| I have used the networks within the programming of a subject to carry out a practical exercise in class | 2.43 | .91 |

| I have been motivated to use social networks as a space to share, generate and divulge knowledge in the future professional field and society in general | 2.3 | .88 |

Differences in social network use by pre-service teachers based on sex, age and educational level they will be teaching

To complete the description of the motives manifested by pre-service teachers for using social networks, the aim was to find out if there are differences according to sex, age or the educational level they were being trained to teach.

Differences in terms of sex

Regarding sex, the results show that this factor scarcely determines the choice or use of social networks. Of the 33 reasons why pre-service teachers may choose to use social networks, only in one case do we find differences in terms of sex. The motive is “Get to know teachers who share interesting materials and content for my training”. Women rated this item more highly than men did. Of the 33 reasons, only one shows differences in terms of sex, allowing for various interpretations. It is possible that women are more inclined towards collaboration and resource exchange on social networks, valuing more highly the access to materials and content which enriches their teacher training. It could also reflect a trend in how women use social networks in an academic context, focusing on the creation of networks and the exchange of knowledge with other professionals.

Differences in terms of age

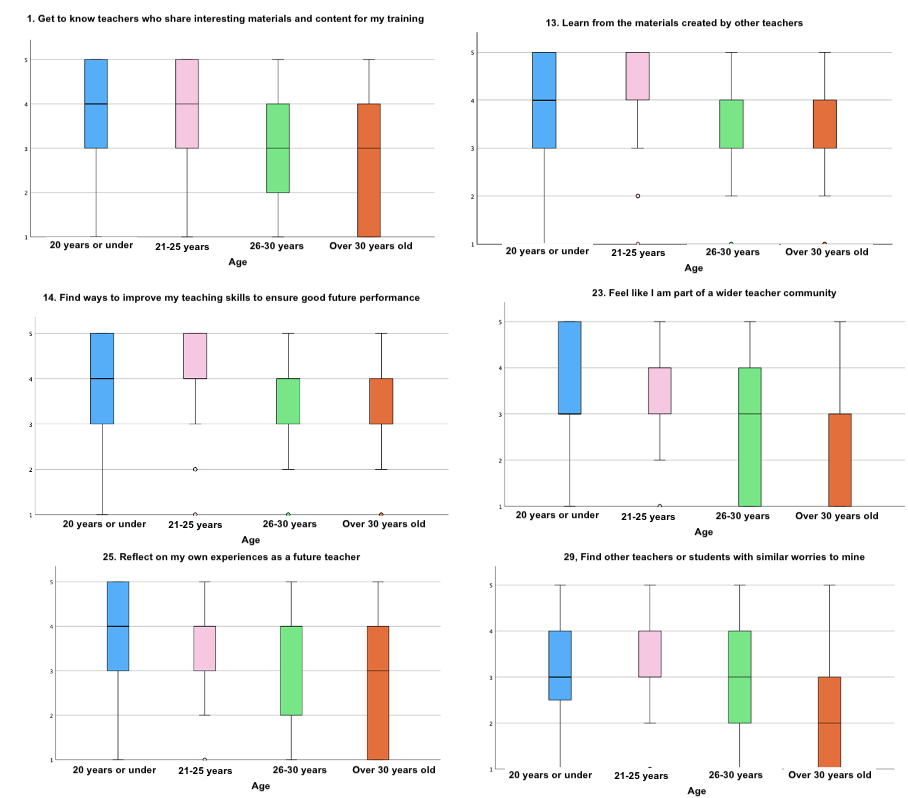

As can be seen in the box plots in Figure 1, there are five motives in which we find differences according to the age of the pre-service teachers, all of which correspond to motives included in the first factor, “Finding resources and people to learn from”. In terms of the differences found, it is the youngest pre-service teachers (20 years old or under and 21-25 years old) who value the motives more positively than older teachers (26-30 years old or more).

According to Dunn´s post Hoc test, in various motives there are differences between students of 20 years old or under and 31 years old or more. Among subjects in the older age groups, the percentage of those who don’t identify with the motives increases, as is the case in items 19 and 23. The youngest teachers rate social networks more highly for reflection, learning about existing materials and belonging to wider communities of teachers, showing a greater need to establish and develop professional networks and skills. Furthermore, older teachers show more variability in their replies, indicating that they may have different aims and priorities in their professional development, having already established their networks and learning methods.

Box plots to represent statistically significant differences by age using the Kruskall-Wallis test

Although reflecting is important for everyone (item 25), the youngest teachers may feel a more urgent need to use social networks for this purpose. Equally, they have more trust in existing materials for their learning (item 13), while older teachers may search for other sources or more personalized learning methods. In general, all the groups consider that it is important to connect with others who share their concerns (item 19), but the youngest teachers are looking for these connections more urgently. In addition, they highly value belonging to a community of teachers (item 23), seeking to establish professional networks early on, perhaps because they are a generation of permanent connection and presence on social networks, and it is more natural for them to understand this type of environment as a space for meeting and socializing. Meanwhile, those over 30 years old may have already established their own professional networks and, therefore, they don’t see this as a priority. Lastly, improving teaching skills (item 14) is a common concern, although it may be less intense in older groups, possibly because they have already acquired a solid skill base in previous years or gained it from their experience. These differences suggest a need to adapt teacher training programs to better meet the expectations and needs of different age groups, promoting a digital inclusion which benefits all future teachers.

Differences in terms of the education level they are training to teach

We also analyzed whether there are significant differences between the perceptions of pre-service teachers in terms of the educational level for which they are training (Figure 2). To carry out this contrast, we began the analysis by contrasting whether there were significant differences between teachers of pre-school and primary education on the one hand, and those of secondary education and vocational training on the other. The analysis showed us that there were no significant differences in any of the items on the scale in the intragroup comparisons. Based on this result, we carried out an analysis of differences between two groups, namely: Undergraduates (students of Early Childhood and Primary Education) and Master's Degree (students for Secondary School and Vocational Training teachers). We found significant differences in 6 of the 33 items that make up the scale. As can be seen in Figure 2, all the average ranges of the different items are higher among undergraduates than among master's students. These items are distributed among the three factors of use, with those found in factor 2 being more predominant (3 of the 6 items).

Average ranges of items with significant differences according to the Mann-Whitney U-test by academic level (Undergraduate or Master's degree)

In the case of the two items that show the greatest variation (items 1 and 23), it is those related to the first of the factors “Find resources and people to learn” that are rated higher by undergraduate students than by master's degree students. We understand that it is the undergraduate students who have higher expectations of what social networks can offer them. Perhaps this motivation can be justified by the higher expectations towards their training and future as teachers on the part of the undergraduate students, together with a need to have experiences that reflect the reality of the classroom, given their lack of teaching practice. Meanwhile, the master’s students may not rate these items so highly since their lack of practical experience and teaching training may lead them to not understand the concrete use that can be made of the resources distributed in social networks.

Furthermore, in those items which correspond to the motives of “Academic Learning” (PC2), undergraduate students have highlighted three of them with greater interest than the master's students. These three items are: “Receive feedback from my teachers”, and “from other colleagues” and “Reflect on my experiences as a teacher”. This may indicate that undergraduate students are beginning to have a greater professional identity, which leads them to value the need to improve their performance as teachers. In this process, they look for mentors to support them in their academic process, and, in their reflection, find a crucial means to understand the reality of the classroom. Master's students, with a lower degree of professional teaching identity may not value the importance of collaboration and feedback in professional improvement, due to their shorter time as future teachers.

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

Social networks are present in the daily lives of the young university population, frequently being used for social interaction, entertainment and access to varied information. However, beyond its recreational use, social networks can play a significant formative function in the learning and professional development of pre-service teachers.

As we have seen, a significant proportion of pre-service teachers are active users of a social network. However, perhaps what Resnik denounced in her conference as president of the AERA in 1987 with respect to school is now also happening with social networks. In her conference, Learning in School and Out (Resnik, 1987), she highlighted how school comprises an individualistic, mental, symbolic and generalist learning that is very different to the world outside school: social, instrumental, contextualized and specific. We could state, based on the results of our research, that the same could be happening in initial teacher training with regards to social networks. There are students who use them inside and outside their training institutions, but they are invisible within the initial training curriculum.

To respond to this issue, we point to three areas that, from our perspective, should be addressed in initial teacher education: social networks and teacher identity and image (Carpenter et al., 2020; Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2014b); social networks and the construction of digital professionalism (Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2014a); and social networks for self-regulated learning.

First, initial teacher training must integrate the digital spaces used by many teachers in training. It is crucial for institutions to approach social networks not only as a communication phenomenon, but also to educate on the associated responsibilities and ethical commitments. Research has highlighted the necessary media literacy of university lecturers in any area of knowledge, highlighting those that train future teachers (Santisteban et al., 2020). Similarly, social networks offer a "window into the classroom" that can give students a realistic understanding of their future school environment, selecting content that is true to reality and avoiding the romanticization of teaching (Carpenter et al., 2017; Staudt Willet, 2024). It cannot be assumed that pre-service teachers, because of their youth, will autonomously identify the most appropriate profiles and content (Staudt Willet, 2024). It is the responsibility of the teaching staff and those responsible for professional development to establish training paths that take advantage of social networks as didactic and pedagogical means for future teachers.

Following this line, the age of students determines their participation in social networks. Younger students, as we have found in this research, identify more with the potential of these platforms and with their possibilities as future teachers. Initial teacher education should take advantage of this positive orientation to highlight both the advantages and challenges of using social networks for future teachers (Carpenter et al., 2023). A recent example is the phenomenon of "sharenting" (Garrido et al., 2023; Otero, 2017), which describes adults exposing the image and private data of minors on social networks such as TikTok without the consent of their guardians. There have been cases of teachers violating the privacy of minors by showing recordings of their students without adequate protection measures (El Día, 2024). However, these cases are isolated if we consider social networks as spaces to make visible good practices of "Teachtokers" or teachers with leadership in social networks (Marcelo & Marcelo-Martínez, 2021), who use these platforms to promote creativity (Vizcaíno-Verdú & Abidin, 2023) and exercise a type of "teacher activism" (Carpenter & Krutka, 2014; Greenhalgh & Koehler, 2017; Krutka et al., 2016).

A second area for action in initial teacher education concerns the development of new digital professionalism (Zinskie & Griffin, 2023). Future teachers will be teachers in a connected society and their initial training should promote professional awareness characterized by connection rather than isolation. Encouraging pre-service teachers to participate in professional social networks can help create a “personal learning network” that supports them at the start and throughout their career. Trainers need to routinely promote and encourage their students to use social networks to supplement the training resources they provide in their classes (Carpenter & Green, 2018; Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2012). It is essential to develop a strategy that allows pre-service teachers to search for information, digital content and identify influential teachers. The results of our study indicate that prospective teachers rarely participate in teacher-organized training activities and processes in social networks. Trainers should therefore integrate these resources into their training programs.

Often, university professors provide an infinite number of bibliographic resources, forgetting that there are complementary sources that can enrich the teaching-learning process. It is necessary to analyze the complementarity or conflict between the pedagogical orientations and resources offered by trainers and those found in social networks, turning this analysis into a learning opportunity. There are numerous documented experiences on the use of social networks as a didactic tool in the training of future teachers (Marcelo-Martínez & Marcelo, 2023). For example, the use of X (Twitter) to develop “microblogging” activities and subject documentation (Tejedor et al., 2021), or Instagram as a space for communication, collaboration and repository of materials (Alonso-López & Terol-Bolinches, 2020; Hernández, 2020). Although higher-education teachers are adopting new innovative methodological strategies, the results of our study show that the integration of social networks as a curricular element to articulate learning activities in the classroom or outside the classroom is perceived as low.

Third, initial teacher education should promote the integration of social networks as another resource for the development of self-regulated learning strategies by pre-service teachers (Yen et al., 2022). In this sense, we found that some pre-service teachers become familiar with social networks not only as a space to obtain resources, but also as another tool in their own personal learning environment and network. The creation of a personal learning network composed of many other future teachers active in social networks, and the need to share problems, doubts and experiences among young people will allow pre-service teachers to develop their own professional digital identity as teachers (Engeness, 2021).

Finally, with respect to the differences in the reasons for use according to gender, age or the educational level for which the pre-service teachers are preparing, it is noteworthy that the youngest teachers attribute greater credibility and usefulness to the use of social networks. This questions whether their use is due to a greater exposure to networks (Marín-Díaz et al., 2019) and the fact they’ve grown up in a digital environment, or to a lack of reflection and tendency towards a more superficial and immediate consumption of information. It is also possible that older teachers, as well as those preparing to teach in secondary school (older than those in early childhood and primary education), have developed greater maturity in the use and access to information on social networks, recognizing their limitations as tools for their professional development.

To conclude, this research has some limitations. First, the data come from a questionnaire that has shown validity and reliability, but whose results are limited to a non-probabilistic sample. Therefore, it would be necessary to expand the sample to respond to the population under study. On the other hand, the results could be expanded to include other methodologies such as interviews or focus groups in order to provide more complete and explanatory information. Finally, the space for analyzing the experience provided by our future teachers remains open. Within the field of secondary education, it is more extensive than the sample, since, in this consideration, the sample could be extended to university students who are being trained in all the specialties offered by the Master's Degree in Teaching in Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate, Vocational Training and Language Teaching.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been developed thanks to the funds from the following R&D&I Projects: PAIDI 2021 funded by the Junta de Andalucía with reference “PROYEXCEL_00826” and R&D&I Project, funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain with reference “TED2021-129820B-I00”.

REFERENCES

Alhabash, S., & Ma, M. (2017). A Tale of Four Platforms: Motivations and Uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat Among College Students? Social Media + Society, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117691544

Alonso-López, N., & Terol-Bolinches, R. (2020). Alfabetización transmedia y redes sociales: Instagram como herramienta docente en el aula universitaria. ICONO-14: Revista científica de Comunicación Audiovisual y Nuevas Tecnologías, 18(2), 138-161. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v18i2.1518

Anderson, M., Faverio, M., & Gottfried, J. (2023). Teens, social media and technology 2023. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/12/11/teens-social-media-and-technology-2023/

Carpenter, J. P., & Krutka, D. G. (2014). How and why educators use Twitter: A survey of the field. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 414-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2014.925701

Carpenter, J. P., & Green, T. D. (2018). Twitter + Voxer: Educators’ complementary uses of multiple social media [Paper presentation]. Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education, Washington, DC. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/182835/

Carpenter, J. P., Morrison, S. A., Craft, M., & Lee, M. (2020). How and why are educators using Instagram? Teaching and Teacher Education, 96, 103149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103149

Carpenter, J. P., Morrison, S. A., Rosenberg, J. M., & Hawthorne, K. A. (2023). Using Social Media in pre-service teacher education: The case of a program-wide twitter hashtag. Teaching and Teacher Education, 124, 104036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104036

Carpenter, J. P., Cook, M. P., Morrison, S. A., & Sams, B. L. (2017). “Why haven’t I tried Twitter until now?”: Using Twitter in teacher education. Learning Landscapes, 11(1), 51-64. https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v11i1.922

Carpenter, J. P., Morrison, S. A., Shelton, C. C., Clark, N., Patel, S., & Toma-Harrold, D. (2024). How and why educators use TikTok: Come for the fun, stay for the learning? Teaching and Teacher Education, 142, 104530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104530

Casipit, D., Cara-Alamani, E., Ravago, J., Reyes, M., Pagay, J., & Tagasa, G. (2022). Gender Differences in Using Social Media in Language and Literature Teaching in Multicultural Context. International Journal of Language and Literary Studies, 4(4), 52-65. https://doi.org/10.36892/ijlls.v4i4.1083

El Día. (2024, 9 de abril). Profesor en Tenerife borra video viral tras quejas de padres.https://www.eldia.es/sociedad/2024/04/09/profesor-tenerife-borra-video-viral-100838689.html

Engeness, I. (2021). Developing teachers’ digital identity: towards the pedagogic design principles of digital environments to enhance students’ learning in the 21st century. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 96-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1849129

Feiman-Nemser, S., & Buchman, M. (1988). Lagunas de las prácticas de enseñanza de los programas de formación del profesorado. In L. M. Villar Angulo (Ed.), Conocimiento, creencias y teorías de los profesores (pp. 301-314). Marfil.

Flores-González, N., Flores-González, E., Castelán-Flores, V., & Zamora-Herández, M. (2022). A didactic tool for updating the teaching-learning process of English as a foreign language. Journal of Information Technologies y Communications / Revista de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicaciones, 6(15). https://doi.org/10.35429/JITC.2022.16.6.20.28

Garrido, F., Alvarez, A., González-Caballero, J., Garcia, P., Couso, B., Iriso, I., Merino, M., Raffaeli, G., Sanmiguel, P., Arribas, C., Vacaroaia, A., & Cavallaro, G. (2023). Description of the Exposure of the Most-Followed Spanish Instamoms’ Children to Social Media. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032426

Gilbert, S. (2016). Learning in a Twitter-based community of practice: an exploration of knowledge exchange as a motivation for participation in #hcsmca. Information, Communication & Society, 19(9), 1214-1232. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1186715

Goodyear, V., Parker, M., & Casey, A. (2019). Social media and teacher professional learning communities. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(5), 421-433. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1617263

Greenhalgh, S. P., & Koehler, M. J. (2017). 28 Days Later: Twitter Hashtags as “Just in Time” Teacher Professional Development. TechTrends, 61(3), 273-281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0142-4

Greenhow, C., & Askari, E. (2017). Learning and teaching with social network sites: A decade of research in K-12 related education. Education and Information Technologies, 22, 623-645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-015-9446-9

Hamedinasab, S., Ayati, M., & Rostaminejad, M. (2023). Teacher professional development pattern in virtual social networks: A grounded theory approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 132, 104211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104211

Hernández, A. M. (2020). Instagram como recurso didáctico en la Educación Superior en los Grados de Infantil y Primaria. Contribuciones de la tecnología digital en el desarrollo educativo y social, 124.

Higueras-Rodríguez, L., Medina-García, M., & Pegalajar-Palomino, M. D. (2020). Use of Twitter as an Educational Resource. Analysis of Concepts of Active and Trainee Teachers. Education Sciences, 10(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10080200

Huebner, E. J. (2022). TikTok and museum education: A visual content analysis. International Journal of Education Through Art, 18(2), 209-225. https://doi.org/10.1386/eta_00095_1

Hyndman, B., & Harvey, S. (2020). Preservice Teachers’ Perceptions of Twitter for Health and Physical Education Teacher Education: A Self-Determination Theoretical Approach. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(4), 472-480. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2019-0278

IAB Spain. (2023). Estudio de Redes Sociales 2023. [Informe]. IAB Spain. https://iabspain.es/estudio/estudio-de-redes-sociales-2023/

Iredale, A., Stapleford, K., Tremayne, D., Farrell, L., Holbrey, C., & Sheridan-Ross, J. (2020). A review and synthesis of the use of social media in initial teacher education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 29(1), 19-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2019.1693422

Karimi, H., Knake, K. T., & Frank, K. A. (2022). Teachers in Social Media: A Gender-aware Behavior Analysis. Proceedings - 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Big Data 2022, 1842–1849. https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData55660.2022.10020354

Kennedy, M. M. (2019). How We Learn About Teacher Learning. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 138-162. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X19838970

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, G. (2014a). Teacher professionalization in the age of social networking sites. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(4), 480-501. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2014.933846

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, G. (2014b). The fragmented educator 2.0: Social networking sites, acceptable identity fragments, and the identity constellation. Computers & Education, 72, 292-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.12.001

Krutka, D. G., Carpenter, J. P., & Trust, T. (2016). Enriching Professional Learning Networks: A Framework for Identification, Reflection, and Intention. TechTrends, 60(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0141-5

Lemon, N., & O'Brien, S. (2019). Social Media use in Initial Teacher Education: Lessons on knowing where your students are. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(12). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2019v44n12.3

Li, S., Zheng, J., & Zheng, Y. (2020). Towards a new approach to managing teacher online learning: Learning communities as activity systems. The Social Science Journal, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2019.04.008

Marcelo García, C., & Marcelo-Martínez, P. (2021). Influencers educativos en Twitter. Analisis de hashtags y estructura relacional. Comunicar: Revista Científica Iberoamericana de Comunicación y Educación, 29(68), 73-83. https://doi.org/10.3916/C68-2021-06

Marcelo-Martínez, P., & Marcelo García, C. (2023). Redes Sociales y Formación del Profesorado. Editorial Octaedro. https://octaedro.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/9788419690715.pdf

Marcelo-Martínez, P., Yot-Domínguez, C., & Marcelo, C. (2023). Los docentes y las redes sociales: usos y motivaciones. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED), 23(72). https://doi.org/10.6018/red.523561

Marcelo-Martínez, P., Yot-Domínguez, C., & Mosquera Gende, I. (2024). Exploring the motives for using social networks for professional development by Spanish teachers, Information and Learning Sciences, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-12-2023-0199

Marín-Díaz, V., Vega-Gea, E., & Passey, D. (2019). Determination of problematic use of social networks by university students. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 22(2), 135-152. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.22.2.23289

Martín-Gutiérrez, Á., Said-Hung, E., & Conde-Jiménez, J. (2024). Social media and non-university teachers from a gender perspective in Spain. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 13(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44322-024-00010-z

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

Mullins, R., & Hicks, D. (2019). “So I feel like we were just theoretical, whereas they actually do it”: Navigating Twitter chats for teacher education. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 19(2), 218-239. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/187335/

Nochumson, T. (2018). An investigation of elementary schoolteachers’ use of twitter for their professional learning. Columbia University.

Nochumson, T. (2020). Elementary schoolteachers’ use of Twitter: exploring the implications of learning through online social media. Professional Development in Education, 46(2), 306-323. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1585382

Otero, P. (2017). Sharenting… ¿La vida de los niños debe ser compartida en las redes sociales? Archivos Argentinos de Pediatría, 115(5), 412-413. https://doi.org/10.5546/aap.2017.412

Patahuddin, S. M., Rokhmah, S., Caffery, J., & Gunawardena, M. (2022). Professional development through social media: A comparative study on male and female teachers’ use of Facebook Groups. Teaching and Teacher Education, 114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103700

Resnik, L. (1987). Learning in School and out. Educational Researcher, 16(9), 13-20. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X016009013

Reyna, J. (2021). #InstaLearn: A Framework to Embed Instagram in Higher Education. In T. Bastiaens (Ed.), Proceedings of EdMedia + Innovate Learning (pp. 164-172). United States: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/219652/

Ruiz-Ruiz, I. N., & Izaguirre, E. J. D. P. (2022). Social media feedback. a different look at instagram as a collaborative learning tool. South Florida Journal of Development, 3(3), 3218-3232. https://doi.org/10.46932/sfjdv3n3-014

Santisteban, A., Díez-Bedmar, M.-C., & Castellví, J. (2020). Critical digital literacy of future teachers in the Twitter Age (La alfabetización crítica digital del futuro profesorado en tiempos de Twitter). Culture and Education, 32, 185-212. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2020.1741875

Schroeder, S., Curcio, R., & Lundgren, L. (2019). Expanding the Learning Network: How Teachers Use Pinterest. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 51(2), 166-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2019.1573354

Staudt Willet, K. B. (2024). Early career teachers’ expansion of professional learning networks with social media. Professional Development in Education, 50(2), 386-402. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2023.2178481

Staudt Willet, K. B. (2019). Revisiting how and why educators use Twitter: Tweet types and purposes in# Edchat. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 51(3), 273-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2019.1611507

Tejedor, S., Coromina, Ó., & Pla-Campas, G. (2021). Microblogging en escenarios curriculares universitarios: el uso de Twitter más allá del encargo docente. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 23. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2021.23.e20.3565

Tess, P. A. (2013). The role of social media in higher education classes (real and virtual). A literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), A60 A68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.032

Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. (2012). Networked Participatory Scholarship: Emergent Techno-Cultural Pressures toward Open and Digital Scholarship in Online Networks. Computers & Education, 58(2), 766-774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.001

Vizcaíno-Verdú, A., & Abidin, C. (2023). TeachTok: Teachers of TikTok, micro-celebrification, and fun learning communities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 123, 103978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103978

Yen, C. J., Tu, C. H., Ozkeskin, E. E., Harati, H., & Sujo-Montes, L. (2022). Social Network Interaction and Self-regulated Learning Skills: Community Development in Online Discussions. American Journal of Distance Education, 36(2), 103-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2022.2041330

Zinskie, C., & Griffin, M. (2023). Initial Teacher Preparation Faculty Views and Practices Regarding E-Professionalism in Teacher Education. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 23(2), 434-455. https://citejournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/v23i2Currentpractice1.pdf

Reception: 01 June 2024

Accepted: 26 September 2024

OnlineFirst: 04 September 2024

Publication: 01 January 2025