Estudios e investigaciones / Research and Case Studies

Evaluation of the use and acceptance of mobile apps in higher education using the TAM model

Evaluación del uso y aceptación de apps móviles en educación superior mediante el modelo TAM

Evaluation of the use and acceptance of mobile apps in higher education using the TAM model

RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, vol. 28, núm. 1, 2025

Asociación Iberoamericana de Educación Superior a Distancia

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional.

How to cite: León-Garrido, A., Gutiérrez-Castillo, J. J., Barroso-Osuna, J. M., & Cabero-Almenara, J. (2025). Evaluation of the use and acceptance of mobile apps in higher education using the TAM

model. [Evaluación del uso y aceptación de apps móviles en educación superior mediante el modelo TAM]. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia,

28(1). https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.28.1.40988

Abstract: The constant use of technology, devices, and mobile applications (apps) has triggered a substantial and important boom in the app and technology industries. For these reasons, the need arises to study and fully understand the impact and adoption of mobile apps by student teachers, who are the future teachers. To address this need, research was conducted using an app acceptance questionnaire based on the Technology Acceptance Model designed and validated for this study. The research involved a total of 205 students enroled in the Information and Communication Technologies Applied to Education course of the Primary Education Degree. Data were collected using a validated questionnaire through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis based on the TAM model. The results revealed highly positive perceptions of the apps by the students, whose mean was 4.4 out of 5 points and a reliability of 94.5%. This supports the strong impact of mobile apps on learning content in university contexts. In conclusion, the highly positive perceptions of the students indicate that applications should be integrated into their training. This integration not only facilitates the learning of specific content, but also promotes the development of new key competencies and various skills, essential for the training of future teachers.

Keywords: educational technology, adoption of mobile apps, Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), higher education, ICT.

Resumen: El uso constante de la tecnología, los dispositivos y las aplicaciones móviles (apps) ha desencadenado un auge sustancial y de gran importancia en las industrias de las apps y la tecnología. Por estos motivos surgió la necesidad de estudiar y comprender profundamente el impacto y la adopción de las apps móviles por parte de los estudiantes de magisterio, quienes son los futuros docentes. Para abordar esta necesidad, se llevó a cabo una investigación utilizando un cuestionario de aceptación de las apps basado en el Modelo de la Aceptación Tecnológica diseñado y validado para este estudio. La investigación involucró a un total de 205 estudiantes matriculados en la asignatura de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación Aplicadas a la Educación del Grado de Educación Primaria. Los datos se recogieron mediante un cuestionario validado a través del análisis factorial exploratorio y confirmatorio en base al Modelo TAM. Los resultados revelaron percepciones altamente positivas de las apps por parte de los estudiantes, cuya media fue de 4.4 sobre 5 puntos y una fiabilidad del 94.5 %. Esto respalda la fuerte repercusión de las apps móviles para el aprendizaje de un contenido en los contextos universitarios. En conclusión, las percepciones altamente positivas de los estudiantes indican que las apps deben integrarse en su formación. Esta integración no solo facilita el aprendizaje de contenidos específicos, sino que también promueve el desarrollo de nuevas competencias clave y diversas habilidades, esenciales para la formación de los futuros docentes.

Palabras clave: tecnología educativa, adopción de apps móviles, Modelo de Aceptación Tecnológica (TAM), educación superior, TIC.

INTRODUCTION

Continuous growth in the adoption of mobile technologies, devices, and applications (mobile apps) has marked a significant and outstanding advance in the technology and application industries in general (Morales et al., 2020; Mellado et al., 2022; Martínez-Gaitero et al., 2024). This phenomenon has contributed to the recognition of contemporary society as part of the so-called fourth industrial revolution, known as the technological revolution (Luna et al., 2019). This revolution implies a rapid and profound transformation of today's society, thanks, among other things, to the integration of technological advances in multiple aspects of daily life, with education being one of the most prominent areas (del Sol Barreto-Cabrera et al., 2024; Martínez-Gaitero et al., 2024).

The integration of technology in education has generated significant changes in the educational field. Specifically, it has facilitated constant and instant access to information, with mobile applications being one of the most widely used technological resources in this context (Luna et al., 2019). This change in educational dynamics has led to a redefinition of teaching and learning methods, where mobile apps play a fundamental role in providing versatile and accessible tools for the acquisition of knowledge and skills.

The use of these tools provides educational opportunities and contributes to constantly improving the teaching-learning process, according to the experiences that users face and develop. Indeed, the educational potential of apps is undeniable, as they can be used in both formal and non-formal educational contexts, according to the contributions of scholars on the subject by Aznar Díaz et al. (2019), Blas et al. (2019), Del-Moral-Pérez and Rodríguez-González (2021), Arts et al. (2021), Martín et al. (2021) and Delgado-Morales and Duarte-Hueros (2023).

According to the contributions of Aznar-Díaz et al. (2019), Hernández et al. (2019), Paredes and Chipia (2020),Mihaylova et al. (2022), Talan (2020), and Jacobs et al. (2023), the insertion of these technologies in education is commonly referred to as mobile learning, which has been the subject of study by various researchers on the subject, also known as mobile-learning. Mobile learning is a methodology by which the aforementioned elements are applied in order to facilitate the teaching-learning process of students, in order to seek the consolidation of knowledge in a more playful, attractive, and motivating way.

In addition, it is characterised as a process that facilitates the acquisition of knowledge in a flexible way, regardless of the location in which the user is located. This approach allows students to access educational content autonomously ( León-Garrido & Barroso-Osuna, 2023). This is due to the positive influence of mobile apps to promote virtual training of users, providing new enriching learning experiences in a continuous and meaningful way (Mihaylova et al., 2022).

From an educational and scientific perspective, the impact and profound impact of mobile learning, mobile apps and devices, specifically smartphones, on society is of great importance. According to the report "Mobile Spain and the World 2022", presented by Ditrendia (Digital Marketing Trends), it was revealed that 5 billion people (63% of the world's population) use the Internet, and specifically 92.4% of them opt for a connection through smartphones. In Spain, it was evident that in 2022 there are more than 55 million mobile lines and that of these, 44 million Spaniards access the Internet through these mobile devices. This indicates the strong repercussions and substantial impact of smartphones on society, suggesting the need to study them to begin designing educational strategies and take advantage of their potential in teaching-learning contexts.

As the years go by, Internet users have a greater number of mobile devices (Mitra et al., 2024; Raj & Tomy, 2024). In fact, 96.6% of society has a smartphone and uses them with an average of 4 hours and 48 minutes through the various existing apps, with more than 3 million apps (Ditrendria, 2022). These indicators mark the presence of mobile devices in society, as well as the considerable impact and participation of users with the use of mobile apps in their daily tasks (López-Padrón et al., 2024; Raj & Tomy, 2024; Mitra et al., 2024; Martínez-Roig, 2024).

These aspects reveal a significant growth of great popularity and importance over mobile apps in everyday life, since these tools contribute to various areas of interest: social, leisure, educational; transforming the way people interact with their social environment. Furthermore, according to various studies such as Chang and Hwang (2018), Liberio (2019), Dorado and Chamosa (2019), Del-Moral-Pérez and Rodríguez-González (2021), Chen et al. (2020), Talan (2020), Prado (2020) support the integration of mobile apps into people's lives, especially in education to increase academic performance, given that their educational nature shows the growing influence and usefulness in these contexts as it has a strong impact on academic performance and student experiences.

With the use of apps in education, greater personalization and adaptation of the teaching-learning process according to the needs of each individual is obtained, increased motivation, individual commitment in the learning process, and interactions between users and multimedia resources. In addition, collaboration between participants is encouraged, generating a constant environment for the exchange of ideas and the construction of knowledge together. All these aspects support the idea and justification of integrating educational technologies in all educational contexts, especially those that allow or seek greater personalization and interactivity in order to seek a strong positive impact on the effectiveness and dynamics of any educational process (Morales et al., 2020; López Carcache, 2022; López-Padrón et al., 2024, Martínez-Roig, 2024).

Based on all of the above and recognising the important impact of mobile apps, the need arises to explore students' perceptions of these resources and examine their use in university educational contexts.

To this end, student teachers of the subject of ICT applied to education participated, using mobile applications that facilitate the teaching and learning process to improve the academic performance of the educational curriculum of primary education. The purpose was to offer tools that they could integrate into their future classes. Mobile apps were used to learn music (Clefs, Perfect Ear, and Rhythm Trainer) which allowed students to access study materials of the curricular content and learning or reviewing a lesson in a dynamic and attractive way. Constant use of each app took place for half an hour, proving to be essential for the development of digital skills and the consolidation of educational knowledge.

The main objective of the research was to design and validate an instrument to evaluate the use and acceptance of mobile apps in higher education students using the Technological Acceptance Model (TAM). The main objective of the research was to design and validate an instrument to evaluate the use and acceptance of mobile apps in higher education students using the technological acceptance model (TAM) to know the use and acceptance of apps in education. This will provide valuable information to critically evaluate the effectiveness and perceived usefulness of these tools in education, thus contributing to the development and improvement of pedagogical practices. The TAM model is a theory developed by Davis (1989) to explain how users come to accept and use new technologies. The central idea of TAM is that the acceptance of a technology by users is mainly influenced by two factors: the perception of usefulness and the perception of ease of use.

METHODOLOGY

Design and Participants

The research design used was ex post facto, using a quantitative approach to evaluate the use and acceptance of mobile apps in higher education students. Purposive sampling was used for the selection of participants with specific characteristics. The sample consisted of a total of 205 students enroled in the Degree in Primary Education of the Faculty of Education Sciences of a Spanish university enroled in the subject "Information and Communication Technologies Applied to Education". They were informed at all times of the research process that was being carried out, in which they participated to contribute to the study of the use and acceptance of mobile apps in education.

Of the total of the study participants, 26.3% (54 individuals) were men, while 73.7% (151 individuals) were women. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 50 years, with a mean age of 19.02 years and a standard deviation of 2.58. All participants participated in the study on a voluntary basis and were informed of the research design before collaborating.

Information Collection Instrument

The instrument was designed based on the contributions of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) proposed by Davis (1989), Urquidi-Martín et al. (2019) and Ursavas (2022). This model examines the different versions of the TAM, including all its versions, the latter being the one that incorporates multiple dimensions to assess the acceptance of the technology. However, attitudes, usability, and behavioural beliefs were highlighted as useful elements to understand the use of technology. Furthermore, feedback on the use of technology based on TAM from Ganjikhah et al. (2017), Cabero-Almenara and Pérez Diez de los Ríos (2018), Cabero-Almenara and Llorente-Cejudo (2020), Gutiérrez-Castillo et al. (2024) and Rodríguez-Sabiote et al. (2023) was considered. Therefore, the original TAM model was adapted with the objective of evaluating the perceptions of university students about mobile applications.

The data collection instrument was administered in the research using a Likert scale, which had to be selected among the 5 possible responses, being 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). This instrument consisted of a total of 30 items and was structured in the following dimensions:

- The perceived utility (PU) was made up of 13 items. The relationships that users have with the use of technology and the ease of learning were studied.

- Attitude towards the use of technology (TA): composed of 9 items. The general and affective disposition of the participants towards the use of mobile apps was evaluated.

- Computer self-efficacy (CSE): constructed of 5 items. Students were studied on the confidence and skills perceived by students through the use of mobile apps.

- Perceived ease of use (PEU): formulated by three elements. Students' perceptions were analysed in relation to the ease of mobile apps, their clarity, and the simplicity of learning content.

- In the same way, sociodemographic issues were integrated to get to know the sample in depth.

Its validation was carried out through the results provided by the students studying the structure provided through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis.

| Factors | Identifier | Affirmation / Questions |

| Perceived Profit | PU1 | The use of apps could improve my learning in the classroom. |

| PU2 | The use of apps in class makes it easier for me to understand certain concepts. | |

| PU3 | I think the use of apps is appropriate when you are learning. | |

| PU4 | I think using an app in the classroom is a good idea. | |

| PU5 | I would like to use apps in future if I had the chance. | |

| PU6 | Using an app would allow me to learn on my own. | |

| PU7 | I would like to use apps to learn both the topics that have been presented to me and others. | |

| PU8 | Is it feasible to integrate apps into educational contexts? | |

| PU9 | With the integration of the apps, it would increase educational experiences. | |

| PU10 | I would voluntarily use apps in my learning. | |

| PU11 | My behaviour would be positively affected when using apps in my learning. | |

| PU12 | Integration of apps would help increase my educational self-image. | |

| PU13 | I believe that the use of apps is beneficial in education. | |

| Attitude towards the use of technology | AT1 | Using an app makes learning more interesting. |

| AT2 | The use of apps will help me to carry out my work as a teacher. | |

| AT3 | Apps are supported for learning content. | |

| AT4 | Apps offer an excellent degree of compliance to meet new expectations and functions in the educational field. | |

| Rat5 | Using apps will help me present clear and concise results. | |

| AT6 | By integrating apps into learning, my motivation increases and my educational needs are met. | |

| AT7 | I enjoy using apps while learning content by playing. | |

| AT8 | Apps are effective and meet learning needs. | |

| AT9 | Apps can be used as a means of evaluating learning. | |

| Computer Self-Efficacy | CSE1 | In general, I consider myself qualified for technical management of audiovisual media and computer science. |

| CSE2 | In general, I consider myself qualified for technical management of the Internet. | |

| CSE3 | In general, I consider myself qualified for the technical management of apps. | |

| CSE4 | You feel control over your learning when using apps in education. | |

| CSE5 | I have no anxiety about the use of apps in education. | |

| Perceived ease of use | PEU1 | I think the app is easy to use. |

| PEU2 | Learning how to use and manage the app has not been a problem for me. | |

| PEU3 | My interaction with the app has been clear and understandable. |

Procedure

In an initial phase of the study, the use of mobile applications in an educational context was introduced, supported by a theoretical justification and explanation that detailed the possibilities of these technological resources for students, addressing advantages and disadvantages. Subsequently, participants were provided with different mobile applications (Clefs, Perfect Ear, and Rhythm Trainer) designed to work with educational musical content of note reading, auditory, and rhythmic development, in order to familiarise them with the functionalities of these tools. The students carried out various musical activities using these applications, both individually and in groups, to understand and assimilate the concepts in a comprehensive way. Students were encouraged to achieve predefined objectives in the applications, which would indicate that they had internalised the content effectively.

Then, two practical sessions of two hours each were scheduled, during which students were able to explore the educational capabilities of these tools and were encouraged to complete the tasks. At the end of this process, the questionnaire designed as a data collection instrument was administered. The assessment tool was provided through the Microsoft Forms platform. Data were collected in the SPSS professional statistics programme in version 29.0. First, an exploratory factor analysis was performed to validate the structure of the questionnaire. Then a confirmation factor analysis was performed using the AMOS v29.0 programme. To verify whether the structure of the questionnaire is adequate to evaluate the use of mobile apps in education. Finally, after knowing the structure of the questionnaire, a descriptive analysis was performed to evaluate the acceptance of the use of mobile apps in education.

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

The analysis of the results was performed with rigorous methodologies. First, the reliability of the instrument was evaluated by determining its internal consistency and structure, thus ensuring the validity of the data collected. Then an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to investigate the underlying structure of the variables under study, based on previously established theoretical dimensions. Subsequently, a confirmation factor analysis (CFA) was performed to validate the structure identified in the EFA. Finally, a descriptive analysis was performed to examine the use of mobile applications, followed by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to detect possible patterns or significant associations between the variables studied. This comprehensive methodological approach ensures the robustness and precision of the results obtained in the study.

Reliability analysis

The reliability analysis (Table 2) reveals that dimension 1 (Perception of Usefulness, PU) and dimension 2 (Attitude towards Technology, TA) show very high reliability coefficients, indicating a remarkable consistency between the elements that make them up. Similarly, dimension 3 (Self-efficacy in Use - CSE) also exhibits a moderately high index of reliability, suggesting an internal consistency in the data collected. However, dimension 4 (Perceived Ease of Use - PEU) shows slightly lower reliability than dimension 3, although it could still be considered moderately high. This could be attributed to less coherence between the items that compose it. Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the four dimensions is 0.955, indicating a high generalised internal consistency.

In summary, the overall analysis of the instrument reveals an outstanding internal consistency that supports its validity and reliability.

| Cronbach's alpha | Number of elements | |

| Dimension 1 (PU) | ,932 | 13 |

| Dimensión 2 (AT) | ,918 | 9 |

| Dimension 3 (CSE) | ,833 | 5 |

| Dimension 4 (PEU) | ,796 | 3 |

| Total TAM Count | ,955 | 30 |

Exploratory Factor Analysis

To perform the Exploratory Factor Analysis (AFE), the maximum likelihood extraction method was used, which seeks to determine the values that maximise the probability of observing the available data. In addition, the Varimax rotation was used, which is a technique that seeks to simplify the interpretation of factors by maximising the variance of the squares of the load coefficients. This rotation, along with Kaiser's normalisation, was done until convergence was reached in 7 iterations. This methodological approach ensures a thorough exploration of the underlying structure of the variables studied, providing a solid basis for the analysis of the data obtained.

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) analysis yielded a coefficient of 0.941, indicating a high adequacy of the data for factor analysis. This value suggests that the correlations between the variables studied are significant and that there is a considerable proportion of shared variance, which supports the suitability of the data for Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Furthermore, Bartlett's sphericity test resulted in a chi-square of 4032.023 with 465 degrees of freedom and a p-value <0.001. This result provides sufficient evidence to support the relevance of the data to perform factor analysis, as it indicates that the correlations between the variables are so non-zero as to proceed with the analysis.

| Rotated Factor Matrix | ||||

| Factors | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| PU1 | ,593 | |||

| PU2 | ,641 | |||

| PU3 | ,656 | |||

| PU4 | ,660 | |||

| PU5 | ,634 | |||

| PU6 | ,600 | |||

| PU7 | ,594 | |||

| PU8 | ,609 | |||

| PU9 | ,702 | |||

| PU10 | ,597 | |||

| PU11 | ,602 | |||

| PU12 | ,527 | |||

| PU13 | ,623 | |||

| AT1 | ,484 | |||

| AT2 | ,607 | |||

| AT3 | ,536 | |||

| AT4 | ,550 | |||

| AT5 | ,436 | |||

| AT6 | ,690 | |||

| AT7 | ,588 | |||

| AT8 | ,585 | |||

| AT9 | ,509 | |||

| CSE1 | ,691 | |||

| CSE2 | ,788 | |||

| CSE3 | ,772 | |||

| CSE4 | ,436 | |||

| CSE5 | ,440 | |||

| PEU1 | ,598 | |||

| PEU2 | ,688 | |||

| PEU3 | ,769 | |||

| Extraction method: maximum similarity. Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalisation. | ||||

| a. The rotation has converged in 7 iterations. | ||||

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

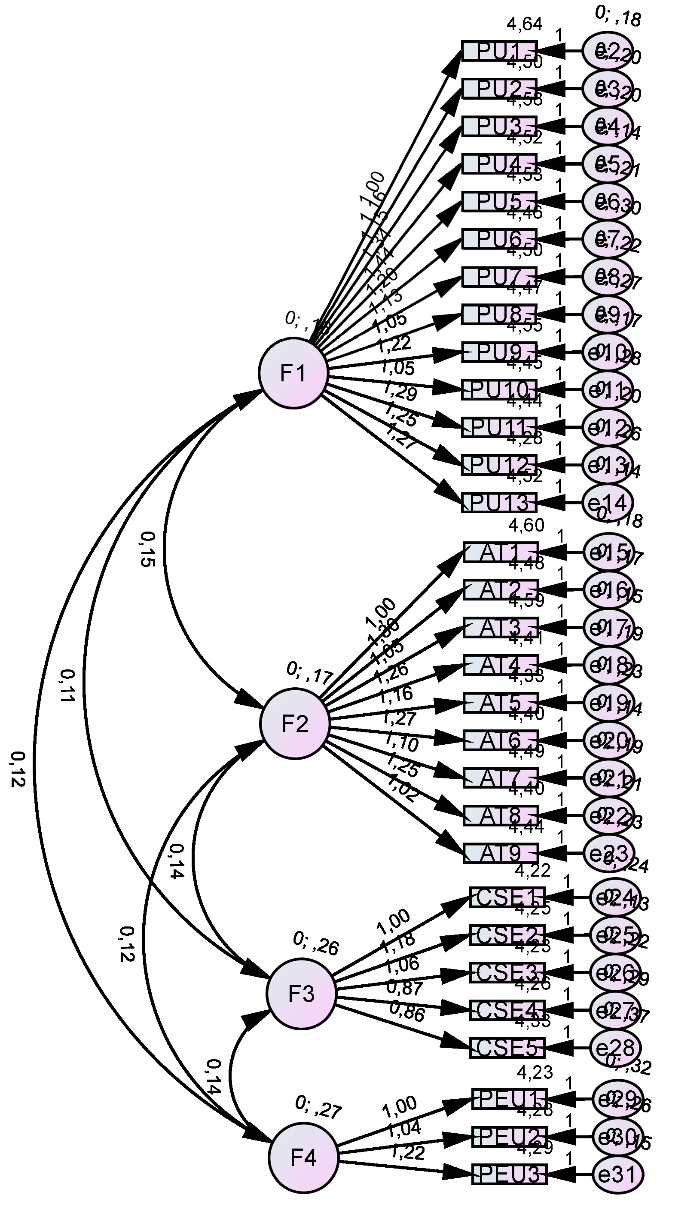

After the application of the EFA, the confirmation factor analysis (CFA) was performed through the AMOS v.29 programme. Figure 1 shows the factor structure of the proposed model.

Path diagram on the structure of the AFE on the TAM model

Note: own elaboration.

In the path diagram that illustrates the structure of the exploratory factor analysis (AFE), various standardised factor loads are observed. The values obtained range from 1.00 to 1.44 for the Perceived Usefulness dimension (PU), between 1.00 and 1.30 for the Attitude towards Technology dimension (TA), between 0.86 and 1.18 for the Self-Efficacy in Use dimension (CSE) and between 1.00 and 1.22 for the Perceived Ease of Use dimension (PEU). In summary, most of the items show a significant factor load, although a couple of items whose values are below 1 were identified. These findings provide a detailed view of the relationship between the variables studied and contribute to a more complete understanding of the underlying structure of the data.

Similarly, and according to Pérez-Gil et al. (2000), Fernández-García et al. (2008), Fernández et al. (2017), Verdugo et al. (2008), and Yucel et al. (2020), it is advisable to contrast these data with several indices of the model to ensure the adjustments with great reliability; therefore, the parsimony indices must be observed: CMIN/DF (Normalised Chi-Square) with a value less than 5 and RMSEA (Square Root Error) with a value between 0.05 and 0.08 for an acceptable model, and less than 0.05 for an adequate model, and the incremental adjustments NFI (Normed Adjustment); IFI (Comparative Adjustment Index).

In the model presented, the following measurement values were obtained: CMIN/DF = 1.931; NFI= 0.814; IFI = 0.901; TLI = 0.891; CFI = 0.900 and RMSEA = 0.068. These statistics show an adequate fit of the model presented, except for the TLI and the NFI, which is below 0.90, although the TLI has a close value. For these reasons, we reviewed the covariance error indices among the proposed ones to study the error values that existed between them and improve the data obtained. After its review, those with a higher error rate were eliminated.

PU1, PU2, PU4, PU5 and AT1 were eliminated, and the data of the described indices were improved, being CMIN/DF = 1.785; NFI = 0.850; IFI = 0.926; TLI = 0.917; CFI = 0.926 and RMSEA = 0.60. These values are more in line with an adequate model, as indicated by the treated authors, compared to the values obtained previously. However, the NFI did not reach the average that indicated reliability of 0.9, the value obtained is 85% validity; therefore, a valid and acceptable model should be considered to know the perceptions of students about mobile apps.

To evaluate the validity of the model after eliminating items and reducing the set to 25 items, the reliability scale was recalculated, with a coefficient of 0.945. This result suggests that the model in question maintains its validity, reliability, and adequacy at 94.5%. Although the coefficient has decreased with respect to the initial value (95.5%), the evaluated indicators show that the latter is higher compared to the initial phase of the study.

Descriptive analysis

To analyse the acceptance of the use of mobile apps in education, according to the dimensions studied with the TAM model, a descriptive analysis of the items in the confirmed model was performed, headed by 4 and 25 items. Table 4 shows: mean, standard deviations, skewness coefficient, kurtosis coefficient, and the confidence level of the mean at 95%.

| Descriptive statistics | ||||||||

| Mean | Standard deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

| Statistical | Standard error | Statistical | Mean | Mean | Lower | Upper | ||

| PU3 | 4,58 | ,045 | ,642 | -1,465 | 1,907 | 4,47 | 4,67 | |

| PU6 | 4,46 | ,051 | ,724 | -1,107 | ,368 | 4,33 | 4,56 | |

| PU7 | 4,50 | ,046 | ,654 | -,947 | -,222 | 4,42 | 4,57 | |

| PU8 | 4,47 | ,047 | ,668 | -,896 | -,346 | 4,39 | 4,56 | |

| PU9 | 4,55 | ,044 | ,637 | -1,094 | ,091 | 4,47 | 4,61 | |

| PU10 | 4,45 | ,047 | ,674 | -,846 | -,437 | 4,36 | 4,52 | |

| PU11 | 4,44 | ,048 | ,681 | -,829 | -,483 | 4,34 | 4,53 | |

| PU12 | 4,28 | ,050 | ,713 | -,473 | -,929 | 4,20 | 4,37 | |

| PU13 | 4,52 | ,044 | ,631 | -,952 | -,145 | 4,44 | 4,59 | |

| AT2 | 4,48 | ,048 | ,683 | -,963 | -,299 | 4,39 | 4,58 | |

| AT3 | 4,59 | ,041 | ,585 | -1,080 | ,178 | 4,51 | 4,66 | |

| AT4 | 4,41 | ,048 | ,684 | -,735 | -,608 | 4,30 | 4,52 | |

| AT5 | 4,33 | ,048 | ,684 | -,533 | -,779 | 4,24 | 4,42 | |

| AT6 | 4,40 | ,045 | ,646 | -,612 | -,604 | 4,31 | 4,49 | |

| AT7 | 4,49 | ,044 | ,631 | -,859 | -,291 | 4,42 | 4,57 | |

| AT8 | 4,40 | ,049 | ,697 | -,717 | -,671 | 4,30 | 4,48 | |

| AT9 | 4,44 | ,045 | ,644 | -,734 | -,482 | 4,37 | 4,51 | |

| CSE1 | 4,22 | ,050 | ,711 | -,345 | -,976 | 4,08 | 4,34 | |

| CSE2 | 4,25 | ,049 | ,708 | -,397 | -,945 | 4,14 | 4,39 | |

| CSE3 | 4,23 | ,050 | ,722 | -,376 | -1,013 | 4,14 | 4,33 | |

| CSE4 | 4,26 | ,049 | ,699 | -,414 | -,900 | 4,18 | 4,37 | |

| CSE5 | 4,33 | ,053 | ,752 | -,632 | -,973 | 4,21 | 4,43 | |

| PEU1 | 4,23 | ,054 | ,769 | -,559 | -,684 | 4,12 | 4,37 | |

| PEU2 | 4,28 | ,052 | ,746 | -,584 | -,738 | 4,17 | 4,38 | |

| PEU3 | 4,29 | ,052 | ,749 | -,538 | -1,038 | 4,18 | 4,39 | |

The data reveal that the average scores of the students' responses are in a narrow range, ranging from 4.22 to 4.59, which corresponds to the categories "strongly agree" and "totally agree", respectively. These results suggest that students of the Bachelor's Degree in Primary Education see mobile applications as effective tools to study and facilitate the learning of content. This is supported by the overall average of 4.4 out of 5 points, indicating a high level of acceptance.

When examining the standard error of the mean, it is observed that the values are consistently low, ranging from 0.041 to 0.054. This low error margin indicates high reliability in the selected sample, which strengthens the validity of the results. Consequently, the findings are highly significant and provide a solid basis for the conclusions derived from the study.

For the measure of dispersion, the standard deviation varies between 0.585 and 0.769, indicating a moderate dispersion of the data. Although it does not approach 1, it suggests some variability in the responses. In terms of asymmetry, the values are between -1.465 and -0.345, indicating a slant to the left side of the distribution and a trend towards lower values on the response scale.

However, kurtosis varies between -1.038 and 1.907, suggesting a less pointed distribution compared to a normal distribution, with positive values indicating a more pointed distribution. In terms of confidence level, the lower and upper ranges are generally narrow, indicating high accuracy in the estimates obtained and reinforcing confidence in the validity of the study's conclusions.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The use of mobile apps in education should help any student to develop new opportunities to build their knowledge through the use of technology, as well as to develop strategies of great importance to improve their continuous training process in higher education (Cabero-Almenara & Llorente-Cejudo, 2020; del Sol Barreto-Cabrera et al., 2024; González-Cervera et al., 2024; Martínez-Gaitero et al., 2024).

In fact, these tools are considered as resources that offer greater personalization and adaptation of the teaching-learning process, since with their integration it is possible to adapt learning at different paces, depending on the individual's need (Morales et al., 2020; López Carcache, 2022; López-Padrón et al., 2024; Martínez-Roig, 2024). Like motivation, it is another element that should be highlighted when integrating mobile apps, as indicated by several scholars on the subject (Arts et al., 2021; Mitra et al., 2024).

Based on the objective of the research that focused on designing and validating an instrument to evaluate the use and acceptance of mobile apps in higher education students through the TAM model, it is stated that the designed instrument meets the expectations of students and is valid to know the acceptance of mobile apps within university educational contexts. Similarly, it is stated that the integration of these technological resources in education has generally been well accepted by students, reaching a rating of 4.4 points out of 5, evidencing that it has a strong impact and acceptance by students. This may be because the use of mobile apps provides greater flexibility in learning content; since it is possible to adapt to the different rhythms of each individual, as well as the learning of the content wherever they want. In addition to these aspects, it should be taken into account that mobile apps are designed to make learning more interactive and engaging, which helps to increase motivation among students. Therefore, greater student participation is achieved.

The high acceptance of mobile apps by students, and in all the dimensions studied (perceived usefulness, attitude towards the use of technology, computer self-efficacy and ease of use), has a reliability level of 94.5%. Therefore, the use of these tools is stated to be effective within the educational context. This is confirmed thanks to other similar studies in which mobile apps have been used to learn some content, such as Arts et al. (2021), Aznar Díaz et al. (2019), Blas et al. (2019), Jacobs et al. (2023), among others.

With this study, it has been shown that mobile applications have great potential in educational settings and are a widely accepted resource for training future teachers. Their widespread integration into education will allow the development of new key competencies and various learning skills (Prado, 2020; Mitra et al., 2024; Raj & Tomy, 2024)

Although the TAM model indicates that these tools have been well accepted, it is essential that users, particularly teachers and future teachers, express their concerns about the quality of the content they offer. This is essential to ensure that the content conveyed in educational contexts is accurate and appropriate. In addition, variability in technological infrastructures and accessibility to mobile devices must be considered. These can be important limitations in the classroom, especially in non-university educational contexts. Although it seems that most young students have access to these devices, economic or technological limitations may arise that affect their participation in the teaching-learning process through mobile applications. Other factors to consider include the computing requirements of the devices and software versions, among others. Despite these limitations, it is crucial to address these challenges to ensure effectiveness and equity in the use of digital tools in education. Despite these nuances, this study stands out for its novelty in confirming that mobile applications in education are perceived as extremely valuable tools to enrich students' learning experiences. Unlike previous research, this analysis shows how the usefulness and ease of use of these tools and students' sense of self-efficacy contribute to a positive attitude toward their integration into the educational environment. Furthermore, the relevance of the flexibility and accessibility offered by applications is underlined, allowing students to learn at their own pace and without the stress associated with more traditional methods. The novelty of the study lies in its detailed focus on how these tools impact the educational experience in a practical and effective way.

However, the real success of the integration of these tools in education will depend especially on addressing the aforementioned concerns: accessibility to these devices, technological infrastructures, requirements or characteristics of the terminal, as well as the integration of content. For these reasons, it is necessary to evaluate existing technology to measure the quality of educational content and thus promote the balanced use of technology in the face of the various disparities that can be faced. For future research, it could be possible to measure the long-term effectiveness of these tools in academic performance and the development of skills to make educational decisions to promote educational quality focused on the use of technology.

LIMITATIONS AND THE FUTURE LINE OF RESEARCH

Although the study included 205 students, this figure may not be enough to guarantee the generalisation of the university education population or the geographical region. Another limitation to highlight is the accessibility of the sample, given that only students of the Degree in Primary Education can be counted, not being able to access other degrees. Therefore, research could be subject to sample bias to know students' perceptions of apps. Likewise, although the indices of the confirmatory factor analysis reached the recommended thresholds, their interpretation could be influenced, such as the quality of the data and the specificity of the model.

As for the future lines of research, the following could be considered: expanding and diversifying the sample to access other degrees and a greater number of university students to achieve a greater generalisation of the sample; monitoring sample bias and/or conducting longitudinal research to observe how perceptions and effectiveness of mobile apps change over time to provide more dynamic and thorough perspectives.

Acknowledgments

The PhD thesis project subsidised by the Ministry of University, belonging to the Training and Mobility subprograms within the State Programme for the Promotion of Talent and its Employability in R+D+i, in order to train future university teachers and researchers within the framework of the statute of research staff of the Spanish state.

REFERENCES

Arts, I., Fischer, A., Duckett, D., & van der Wal, R. (2021). Information technology and the optimisation of experience – The role of mobile devices and social media in human-nature interactions. Geoforum, 122, 55-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.03.009

Aznar Díaz, I., Cáceres Reche, M. P., Trujillo Torres, J. M., & Romero Rodríguez, J. M. (2019). Impacto de las apps móviles en la actividad física: un meta-análisis (Impact of mobile apps on physical activity: A meta-analysis). Retos digitales, 36, 52-57. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v36i36.66628

Blas, D., Vázquez-Cano, E., Morales, M. B., & López, E. (2019). Uso de apps de realidad aumentada en las aulas universitarias. Campus Virtual, 8(1), 37-48. http://uajournals.com/ojs/index.php/campusvirtuales/article/view/379

Cabero Almenara, J., & Llorente Cejudo, C. (2020). La adopción de las tecnologías por las personas mayores: aportaciones desde el modelo TAM (Technology Acceptance Model). Publicaciones, 50(1), 141-157. https://doi.org/10.30827/publicaciones.v50i1.8521

Cabero-Almenara, J., & Pérez Díez de los Ríos, J. L. (2018). Validación del modelo TAM de adopción de la Realidad Aumentada mediante ecuaciones estructurales. Estudios sobre Educación, 34, 129-153. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.34.129-153

Chang, C. Y., & Hwang, G. J. (2018). Effects of mobile learning on students’ academic achievement and cognitive load: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 24, 109-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.003

Chen, Z., Chen, W., Jia, J., & An, H. (2020). The effects of using mobile devices on language learning: a meta-analysis. Educational Technology Research and Development: ETR & D, 68(4), 1769-1789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09801-5

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Del-Moral-Pérez, M. E., & Rodríguez-González, C. (2021). Revisión sistemática de investigaciones sobre videojuegos bélicos (2010-2020). Revista de Humanidades, 42, 205-228. https://doi.org/10.5944/rdh.42.2021.27570

Del Sol Barreto-Cabrera, Y., Suárez Perdomo, A., & Castilla-Vallejo, J. L. (2024). Perfiles de uso problemático de los videojuegos y su influencia en el rendimiento académico y los procesos de toma de decisiones en alumnado universitario. Pixel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 69, 287-287. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.101940

Delgado-Morales, C., & Duarte-Hueros, A. (2023). Una Revisión sistemática de instrumentos que evalúan la calidad de aplicaciones móviles de salud. Pixel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 67, 35-58. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.97867

Ditrendia (2022). Informe Mobile España y el Mundo. In Ditrendia. Digital Marketing Trends. https://www.amic.media/media/files/file_352_3500.pdf

Dorado, C., & Chamosa, M. E. (2019). Gamificación como estrategia pedagógica para los estudiantes de medicina nativos digitales. Investigación en Educación Médica, 32, 61-68. https://doi.org/10.22201/facmed.20075057e.2019.32.18147

Fernández, M., Benítez, J. L., Pichardo, M. C., Fernández, E., Justicia, F., García, T., García-Berbén, A., Justicia, A., & Alba, G. (2017). Análisis factorial confirmatorio de las subescalas del PKBS-2 para la evaluación de las habilidades sociales y los problemas de conducta en educación infantil. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 8(22). https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v8i22.1415

Fernández-García, E., Sánchez-Bañuelos, F., & Salinero-Martín, J. (2008). Validación y adaptación de la escala PACES de disfrute con la práctica de la actividad física para adolescentes españolas. Psicothema, 20(4), 890-895. https://doi.org/https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8746

Ganjikhah, A., Rabiee, A., Moghaddam, D. K., & Vahdat, D. (2017). Comparative analysis of bank’s ATM and POS technologies by customers. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 8(3), 831. https://doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v8i3.528

González-Cervera, A., Martín-Carrasquilla, O., González-Arechavala, Y. (2024). Validación de contenido de una escala sobre actitudes hacia la programación y el pensamiento computacional en docentes de Primaria a partir del método Delphi. Píxel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 70, 61-76 https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.103692

Gutiérrez-Castillo, J. J., León-Garrido, A., Barroso-Osuna, J. (2024). The makey-makey board in university classrooms: a study of the perception of this tool using the technology acceptance model. JERI – International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 2.

Hernández, H., Castañeda, L. J., Bravo, A., & Hernández, A. (2019). Tecnología educativa en la educación superior. In J. E. Márquez- Díaz (Ed.), Educación, ciencia y tecnologías emergentes para la generación del siglo 21 (1.. ed., pp. 64-78). Editorial Universidad de Cundinamarca. https://doi.org/10.6084/ijact.v8i3.786

Jacobs, E., Garbrecht, O., Kneer, R., & Rohlfs, W. (2023). Game-based learning apps in engineering education: requirements, design and reception among students. European Journal of Engineering Education, 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2023.2169106

León-Garrido, A., & Barroso-Osuna, J. M. (2023). Modelos y modalidades educativas basados en tecnología educativa: Una revisión bibliográfica. Edutec. Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa, 86, 96-115. https://doi.org/10.21556/edutec.2023.86.2941

Liberio, X. P. (2019). El uso de las técnicas de gamificación en el aula para desarrollar las habilidades cognitivas de los niños y niñas de 4 a 5 años de Educación Inicial. Revista Conrado, 15(70), 392-397. https://bit.ly/3xIe1qs

López Carcache, A. (2022). Dispositivos móviles como estrategia educativa en la universidad pública en modalidad presencial desde la experiencia de estudiantes y profesores de grado. Revista Torreón Universitario, 11(30), 76-92. https://doi.org/10.5377/rtu.v11i30.13395

López-Padrón, A., Mengual-Andrés, S., & Hermann Acosta, E. A. (2024). Uso académico del smartphone en la formación de posgrado: Percepción del alumnado en Ecuador. Píxel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 69, 97-129. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.102492

Luna, U., Rivero, P., & Vicent, N. (2019). Augmented reality in heritage apps: Current trends in Europe. Applied Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 9(13), 2756. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9132756

Martin, A. J., Strnadová, I., Loblinzk, J., Danker, J. C., & Cumming, T. M. (2021). The role of mobile technology in promoting social inclusion among adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(3), 840-851. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12869

Martínez-Gaitero, C., Dennerlein, S. M., Dobrowolska, B., Fessl, A., Moreno-Martínez, D., Herbstreit, S., Peffer, G., & Cabrera, E. (2024). Connecting actors with the introduction of mobile technology in health care practice placements (4D project): Protocol for a mixed methods study. JMIR Research Protocols, 13, e53284. https://doi.org/10.2196/53284

Martínez-Roig, R. (2024). Robots sociales, música y movimiento: percepciones de las personas mayores sobre el robot Pepper para su formación. Píxel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 70. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.104621

Mellado-Moreno, P. C., Patiño-Masó, J., Ramos-Pardo, F. J., & Estebanell-Minguell, M. (2022). Discursos en Facebook y Twitter sobre el uso educativo de móviles en el aula. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 80, 225-240. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2022-1541

Mihaylova, M., Gorin, S., Reber, T. P., & Rothen, N. (2022). A meta-analysis on mobile-assisted language learning applications: Benefits and risks. Psychologica Belgica, 62(1), 252-271. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.1146

Mitra, S., Kroeger, C. M., Wang, T., Masedunskas, A., Cassidy, S. A., Huang, R., Fontana, L., & Liu, N. (2024). Gamified smartphone-app interventions on behaviour and metabolic profile in patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. In Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. IOS Press. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI231284

Morales, J. C., Ramírez, N. E., Vargas, S. H., & Peñuela, A. J. (2020). Uso de aplicativos móviles en el aula y sus factores determinantes. Formación Universitaria, 13(6), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062020000600013

Paredes, Y., & Chipia, J. (2020). Construcción de una jornada virtual sobre Covid-19 a través de Telegram. Revista del Grupo de Investigación en Comunidad y Salud, 5(2), 18-34. http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/gicos/article/view/16616

Pérez-Gil, J. A., Chacón-Moscoso, S., & Moreno-Rodríguez, R. (2000). Validez de constructo: el uso del análisis factorial exploratorio-confirmatorio para obtener evidencias de validez. Psicothema, 12(2), 442-446. https://doi.org/https://www.psicothema.com/pi?pii=601

Prado, F. (2020). El aprendizaje móvil y los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible en la educación superior. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 12(4), 230-233. http://bit.ly/384rCyb

Raj, A., & Tomy, P. (2024). An experimental study on the influence of instructional mobile applications in enhancing listening comprehension of rural students in India. Frontiers in Education, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1280868

Rodríguez-Sabiote, C., Valerio-Peña, A. T., & Batista-Almonte, R. (2023). Validación de una escala del Modelo Ampliado de Aceptación de la Tecnología en el contexto dominicano. Píxel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 68, 217-244. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.100352

Talan, T. (2020). The effect of mobile learning on learning performance: A meta-analysis study. Educational Sciences Theory & Practice, 20(1), 79–103. https://doi.org/10.12738/jestp.2020.1.006

Urquidi Martin, A. C., Calabor Prieto, M. S., & Tamarit Aznar, C. (2019). Entornos virtuales de aprendizaje: Modelo ampliado de aceptación de la tecnología. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 21, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2019.21.e22.1866

Ursavaş, Ö. F. (2022). Conducting technology acceptance research in education: Theory, models, implementation, and analysis. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10846-4

Verdugo, M. A., Crespo, M., Badía, M., & Arias, B. (2008). Metodología en la investigación sobre discapacidad. Introducción al uso de las ecuaciones estructurales. KADMOS.

Yucel, S. C., Ergin, E., Orgun, F., Gokçen, M., & Eser, I. (2020). Validity and reliability study of the Moral Distress Questionnaire in Turkish for nurses. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 28. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2960.3319

Reception: 01 June 2024

Accepted: 23 August 2024

OnlineFirst: 16 October 2024

Publication: 01 January 2025