Estudios

Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on teacher tweeting in Spain: needs, interests, and emotional implications

El impacto de la pandemia de Covid-19 en los tweets de los profesores en España: necesidades, intereses e implicaciones emocionales

Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on teacher tweeting in Spain: needs, interests, and emotional implications

Educación XX1, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 185-208, 2023

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International.

Received: 21 September 2022

Accepted: 24 February 2023

Published: 13 June 2023

How to reference this article: Moreno-Fernández, O., & Gómez-Camacho, A. (2023). Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on teacher tweeting in Spain: needs, interests, and emotional implications.

Educación XX1, 26(2), 185-208. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.34597

Abstract: The dissemination of Covid-19 imposed the confinement of a large part of the world’s population. For this reason, face-to-face classes in Spain were interrupted and did not resume until September 2021. The situation forced schools to move both teaching and communication between teachers to a digital environment, which favoured greater use of social networks. This paper conducts an exploratory study of 30751 tweets extracted from eight educational hashtags (#eduhora, #claustrovirtual, #SerProfeMola, #otraeducaciónesposible, #claustrotuitero, #profesquemolan, #orgullodocente, and #soymaestro) used by the educational community of teachers in Spain. A semantic content analysis is carried out using a mixed methodology based on public data mining and sentiment analysis. The analysis of the data provided novel information about the needs, interests and concerns, as well as the emotional implications that teachers expressed on the social network Twitter during the transition to virtual teaching. The lock-in situation was associated with increased emotional content in the tweets analysed in the sample, irrespective of the positive, negative or neutral polarity of the tweets. The results also show that teachers in Spain use social networks both for professional development and emotional support and that this trend has increased after Covid-19. The use of Twitter is linked to continuous professional development in times of particular difficulty, also in Spain, as has been the case in other countries. The findings of the study show that the historical Twitter archive is a valid resource for the analysis of teachers’ feelings in longitudinal research including the Covid-19 period.

Keywords: Twitter, Covid-19, teachers, professional development, content analysis.

Resumen: La difusión del Covid-19 impuso el confinamiento de gran parte de la población mundial. Por este motivo, en España las clases presenciales se interrumpieron y no se reanudaron hasta septiembre de 2021. La situación obligó a los centros educativos a trasladar tanto la docencia como la comunicación entre el profesorado a un entorno digital, lo que favoreció un mayor uso de las redes sociales. Este trabajo realiza un estudio exploratorio de 30751 tweets extraídos de ocho hashtags educativos (#eduhora, #claustrovirtual, #SerProfeMola, #otraeducaciónesposible, #claustrotuitero, #profesquemolan, #orgullodocente, y #soymaestro) utilizados por la comunidad educativa de profesores en España. Se realiza un análisis semántico de contenidos que utiliza una metodología mixta basada en la minería de datos públicos y el análisis de sentimientos. El análisis de los datos proporcionó información novedosa sobre las necesidades, los intereses y las preocupaciones, así como las implicaciones emocionales que el profesorado expresó en la red social Twitter durante la transición a la enseñanza virtual. La situación de encierro se asoció con el aumento del contenido emocional en los tuits analizados en la muestra, independientemente de la polaridad positiva, negativa o neutra de los mismos. Los resultados muestran también que el profesorado en España utiliza las redes sociales para el desarrollo profesional y el apoyo emocional, y que esta tendencia ha aumentado después del Covid-19. El uso de la red social Twitter se vincula con el desarrollo profesional continuo en momentos de especial dificultad en España, al igual que ha sucedido en otros países. Las conclusiones del estudio ponen de manifiesto que el archivo histórico de Twitter es un recurso válido para el análisis de los sentimientos del profesorado en investigaciones longitudinales que incluyan el periodo de Covid-19.

Palabras clave: Twitter, Covid-19, profesorado, desarrollo profesional, análisis de contenido.

INTRODUCTION

Covid-19 has had very negative effects on education globally and has presented very complex challenges in this area (Harris, 2020; Rehm et al., 2021). However, the review of the literature on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on teaching and learning suggests that the pandemic provides an opportunity to pave the way for the introduction of digital education (Pokhrel & Chhetri, 2021).

In the case of Spain, several studies describe the negative effect on teachers of the confinement of the entire Spanish population between March and June 2020, and the suspension of face-to-face classes until September 2021.

Online communities have been proved to be a very effective tool for communication between teachers (Rehm et al., 2021). Trust et al. (2016) defined an online community as a network where individuals share practice-based knowledge. Research by Greenhow et al. (2021) and Xing and Gao (2018) suggests that online teachers’ communities have increased worldwide during the global pandemic of Covid-19 in response to new educational challenges.

Participants in the study by Trust et al. (2016) described professional learning networks for teachers as diverse and multifaceted networks of people, communities, tools, platforms, resources and sites. They also highlighted the affective, social, cognitive and identity benefits of the experiences.

Twitter provides a social networking platform for the voluntary online professional teaching activities. After an exhaustive review of the literature on the topic, Carpenter and Krutka’s (2015) survey showed that for many teachers Twitter facilitates positive, collaborative professional activities and helps combat various forms of isolation. Subsequent research (Trust et al., 2020; Xing & Gao, 2018) describes the strong interest of educators in participating in social networking communities such as Twitter but also the different approaches used by scientific literature to study this phenomenon.

From another perspective, Nochumson (2020) suggests that Twitter may have a strong value as a legitimate platform for lifelong learning and for keeping teachers in the profession.

Research on Twitter has often turned to educational hashtags to analyse how teaching communities have used social media (Greenhalgh et al., 2021). Carpenter et al. (2020) analyse educators’ activity on more than 2.6 million tweets posted using 16 education-related hashtags. Their study demonstrates that Twitter hashtags aid the exchange of ideas, organisation, activism, leadership and the development of social capital by educators.

Undoubtedly, the most studied educational hashtag in the literature is #Edchat (Gao & Li, 2017; Willet, 2019). For example, Greenhow et al. (2021) analyse over half a million tweets with this hashtag during the pandemic to remotely investigate the transition to emergency teaching. Willet (2019) uses Carpenter and Krutka’s (2014) survey on how and why educators use Twitter to analyse over 1.2 million #Edchat tweets. Their data suggest that this social network was preferentially used to explore ideas and share feelings.

Semingson and Kerns (2020) and Trust et al. (2020) use #remoteteaching and #remotelearning to analyse teacher activity during Covid-19. Both hashtags were used to share pedagogical resources and receive online support also in Spain (Beardsley et al., 2021). Rosell-Aguilar (2018) concludes that the #MFLtwitterati hashtag itself constitutes a virtual community of language teachers both in terms of the profile of the hashtag users and the practices and beliefs presented. Parrish and Martin (2022) reached a similar conclusion with the #MTBoS hashtag for mathematics teachers. Educational Twitter hashtags in languages other than English have also been used for educational research. For example, Greenhalgh et al. (2021) in France, Gómez and Journell (2017) in Spain and Zhou and Mou (2022) in China.

Teachers’ communities use Twitter to share content related to their professional activity ( Carpenter & Krutka, 2015; Luo et al., 2020) and to express emotional content (Carpenter et al., 2020). The most frequent themes reported in the literature are: asking and answering questions; sharing and finding teaching-related resources; reflection; dialogue; and emotional support ( Galvin & Greenhow, 2020). Since Covid-19 the most popular topics requested by teachers on Twitter were related to online learning (Greenhow et al., 2021), the use of educational technology and teaching resources (Rehm et al., 2021).

Recent research on teacher communities gathered around educational hashtags has been based on Gee’s (2017) concept of affinity space applied to Twitter for educators (Carpenter et al., 2021; Greenhalgh et al., 2020). Public relations established on Twitter have been described in detail in previous research (Sailunaz & Alhajj, 2019). For example, Greenhalgh et al. (2020) analyse teachers’ interactions through a specific hashtag based on likes, retweets, replies and mentions.

Emotional content in educational research has been related to online teaching, professional development and educational communities (Arora et al., 2021). Emotional content analysis is performed using Sentiment Analysis (SA), also called Opinion Mining. Although there are several methods to perform this analysis, Machine Learning-based sentiment analysis is the most widely used for this purpose in educational research (Zhou & Ye, 2020), especially in the Spanish-speaking context (Osorio et al., 2021). The study by Harron and Liu (2022) demonstrates that the Twitter historical archive is a valid resource for teacher sentiment analysis in longitudinal research that includes the Covid-19 period.

A very promising scope for sentiment interpretation on Twitter is the analysis of emojis ( Li et al., 2022); but we have not found significant educational research applying visual sentiment analysis. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of this method in informal Spanish-language texts (Fernández-Gavilanes et al., 2018).

PURPOSE AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The study presented here expands on the knowledge available to date on the role of Twitter as a social network and a space for teacher interaction before and after Covid-19. The pandemic marks a before and after in educational environments, moving the teaching-learning processes from a physical space such as the classroom to a virtual space such as online learning. Although several studies have explored the activity of teachers on Twitter, few have compared this activity before and after the pandemic. Thus, we sought to understand the influence of the pandemic on teachers’ use of the social network Twitter, as well as to determine changes, if any, in activity, topics of interest, interactions and feelings. We did this by answering four research questions:

- RQ1. How did Covid-19 impact teachers’ Twitter activity?

- RQ2. What topics did teachers tweet about before and after Covid-19?

- RQ3. How did teachers interact on Twitter before and after Covid-19?

- RQ4. How did teachers’ feelings on Twitter evolve before and after Covid-19?

METHOD

This study uses digital data retrieved from social media platforms, in this case specifically Twitter (Greenhalgh et al., 2021; Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2018). We selected the social network Twitter because it is the most widely used by teacher education communities (Luo et al., 2020). We used a mixed methodology based on public data mining and sentiment analysis. This methodology involves the use of digital crawling data in order to more effectively collect, organise and analyse generalisable samples of data representing people in virtual learning and communication environments (Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2018).

Data collection

Using the Twitter v2 API, we collected 18,129 tweets with the hashtags #eduhora, #claustrovirtual, #SerProfeMola, #otraeducaciónesposible, #claustrotuitero, #profesquemolan, #orgullodocente, and #soymaestro, from 1 March 2020 to 31 March 2022 (hereafter referred to as “After Covid-19”). In Spain, these dates cover the periods of confinement, state of alarm and new normality. To compare how teachers’ Twitter engagement in Spain may have changed, we also collected 12,622 tweets with the same hashtags posted between 1 January 2018 and 28 February 2020 (hereafter referred to as “Before Covid-19”). For the analysis of the tweets, punctuation marks and unnecessary characters were removed from the JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) encoding of the Twitter API. Our final dataset included 30,751 tweets along with associated metadata as evidence of an interaction.

Data analysis

To answer the first research question, we calculated the monthly count of all tweets posted before and after Covid-19.

To answer the second research question, we conducted a content analysis of tweets in each of the study periods (Carpenter et al., 2020).

This analysis aimed to determine whether there are differences in the topics discussed by teachers before and after Covid-19 (Gao & Li, 2017). To do so, we performed a semantic content analysis (Neuendorf, 2017) based on public data mining (Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2018). We identified keywords in each of the periods of the study with Sketch Engine (SE), which was considered appropriate due to its ability to process natural languages and its exploratory nature (Del Olmo & Arias, 2021). Specifically, we used the keyness parameter to measure the relevance of the topics in each of the two corpora (Firoozeh et al., 2020). Keyness measures the “statistical significance” of terms concerning a reference corpus of 16 billion SE “Spanish Web 2018” words (Firoozeh et al., 2020): words with a high value in this parameter provide the representation of socially important concepts in the sample (Scott, 1997).

To answer the third research question, we first analysed the metadata associated with the public metrics of the Twitter v2 API as evidence of an interaction. We performed a descriptive statistical analysis of the interactions by month. Next, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the content of each of the tweets published during the months in which an increase in retweets, replies and likes was detected; to do that, the qualitative analysis software Atlas.ti (v.9) was used to extract the most significant examples. Previous categories were determined that coincident with the topics identified with SE within the second research question. This analysis was also used in response to RQ4.

To answer the fourth research question, we first performed Sentiment Analysis (SA) with Google’s Natural Language API, which rated the emotional content of each tweet on a scale between -1 and +1. Following the formula validated by Quintana-Gómez (2021), we converted these data into a text label and considered a positive sentiment polarity for the values collected between 1 and 0.3, a neutral polarity between 0.2 and -0.2, and a negative polarity between -0.3 and -1. Next, we performed a sentiment analysis on the visual data. For this purpose, we identified the most frequent emojis in the sample (Fernández-Gavilanes et al., 2018) and related them to SA.

RESULTS

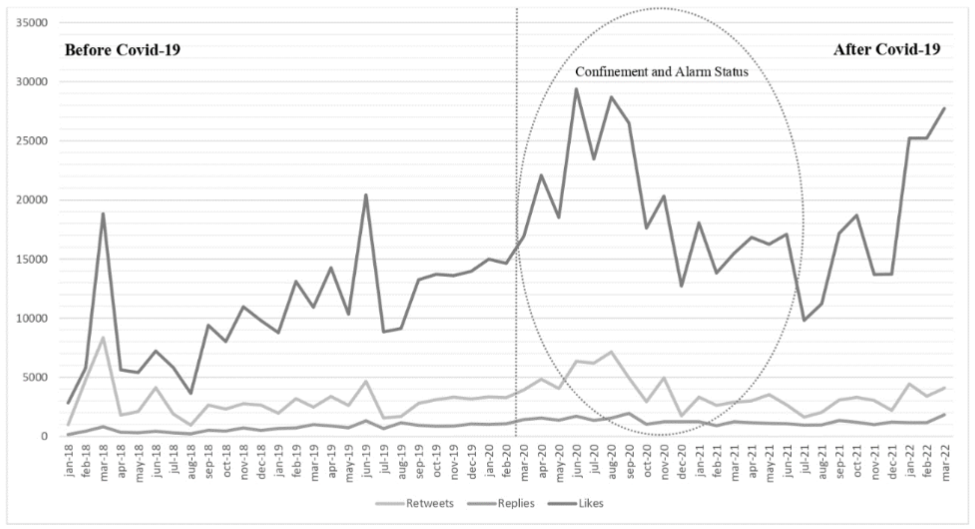

RQ1. How did Covid-19 impact teachers’ Twitter activity?

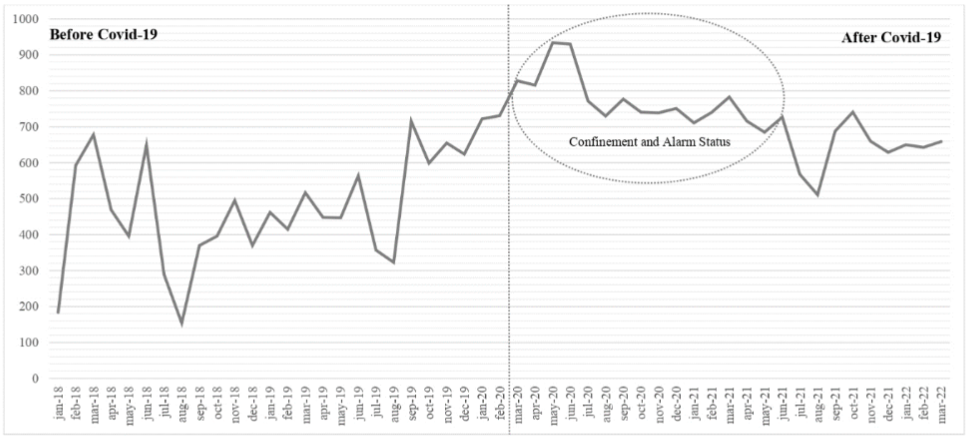

The results show a significant increase in teacher activity on Twitter during Covid-19 ( Figure 1), accentuated during the confinement period between March and June 2020. This increase coincides with the closure of schools in Spain and the generalisation of online teaching. This trend becomes more nuanced after the lockdown period; in the subsequent period, which we have termed the State of Alarm period (between July 2020 and May 2021), teacher activity on Twitter considerably decreased. After the alarm period, teachers’ Twitter usage returns to December 2019 levels.

The partial drop-in activity during the quarter of June, July and August is insignificant because it coincides with the school summer holiday period in Spain. Despite this, Twitter activity during the holiday quarter throughout confinement was higher than during school holidays in the rest of the periods analysed.

Figure 1

Teachers’ activity on Twitter during Covid-19

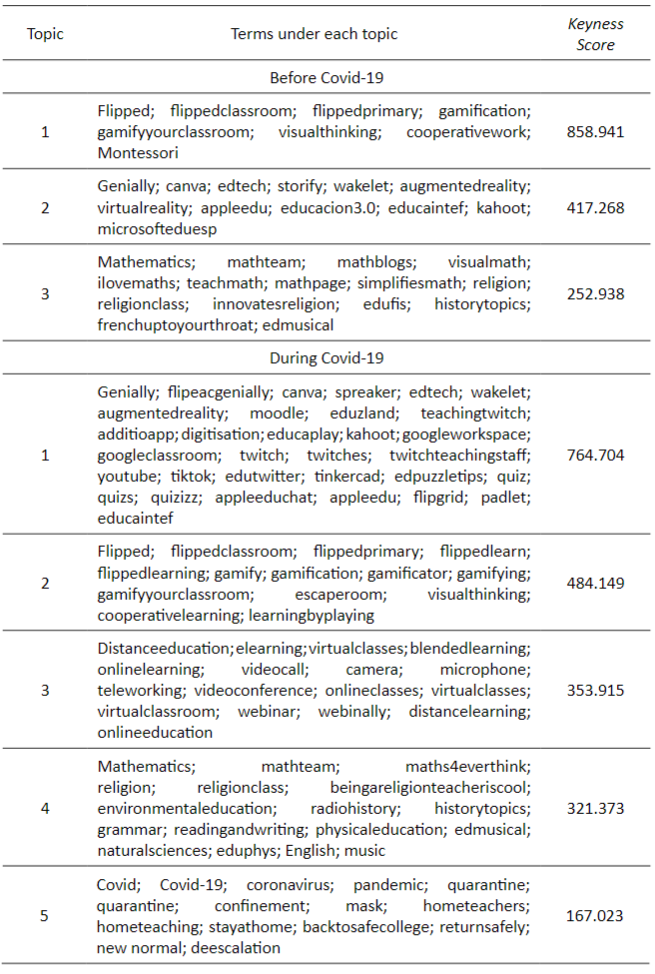

RQ2. What topics did teachers tweet about before and after Covid-19?

To determine the relevance of the topics that teachers posted on Twitter before and after Covid-19, we used the SE keyness score. Only topics with a keyness value higher than 150 were estimated. Based on these results, we have identified eight topics: 3 topics before Covid-19 and 5 topics after Covid-19 (Table 1). Our analysis suggests that in both periods there is a repeated interest in new learning techniques such as flipped classroom, gamification or cooperative work, and in technological resources such as Genially or Canva.

Before Covid-19, teachers tweeted to find and share new learning methodologies and techniques (Topic 1), as well as educational technology for e-learning (Topic 2). We also found that teachers of subjects such as mathematics and religion were the most active on Twitter before the pandemic (Topic 3). After Covid-19, there was continued interest in topics related to free digital resources for the classroom (Topic 1), and new models of e-learning (Topic 2).

Keywords extracted with SE allowed us to identify the most relevant technological tools in this period for teachers in Spain: Genially; augmented reality; Apple Education; Wakelet; Flipgrid; Quiz; Canva; Webinar; Tinkercad; Twitch; Edpuzzle; YouTube; Educaplay; Kahoot; Additio; Moodle; Eduzland; Spreaker; Instagram; and Google Classroom. Before the pandemic, fewer and significantly less relevant resources were listed: Genially; Storify; Wakelet; Apple Education; and Canva.

Our results suggest an increased activity by Spanish teachers of school subjects such as languages, natural sciences and social sciences, in addition to the interventions of mathematics and religion teachers that were already present before the Covid-19 period (Topic 4).

In this period, two new topics directly related to the pandemic appeared. First, a topic related to distance education, e-learning and virtual classrooms (Topic 3). Next, teacher concerns linked to the coronavirus appeared (Topic 5); this topic is strongly linked to emotional content. For example, during the lockdown, teachers tweeted about wearing masks and the importance of staying at home, and the de-escalation afterwards was about the new normal and the safe return to face-to-face classes.

Topics generated by SE analysis based on the keyness score

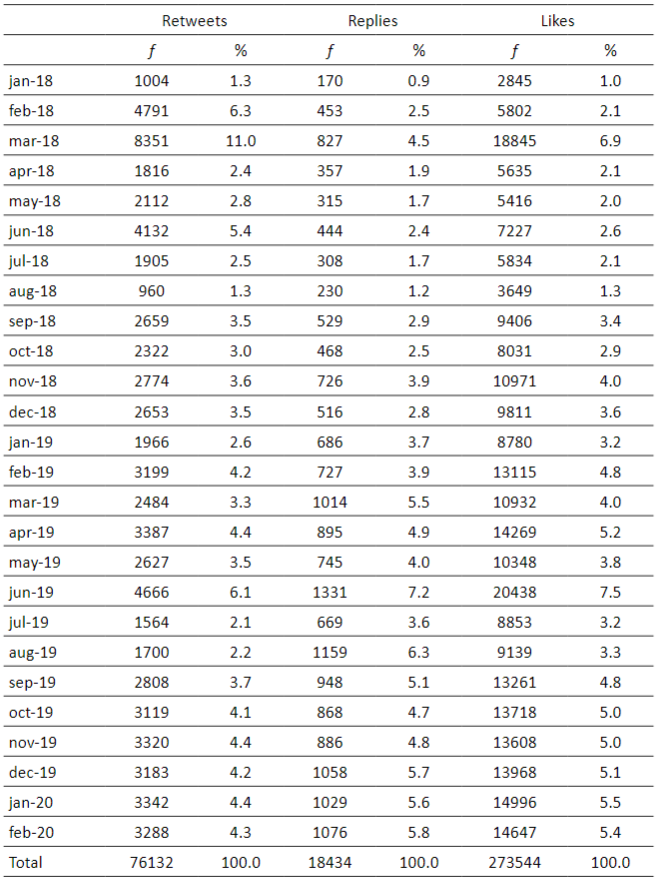

RQ3. How did teachers interact on Twitter before and after Covid-19?

Teachers can interact with Twitter in four different ways: reading, replying (reply), sharing (retweet), or mentioning that they like a tweet. In this study, we were unable to analyse the number of users who read each tweet because this data is not available in the public metrics of the Twitter API. Replies were the least frequent, both before and after Covid-19. Before Covid-19, the months that accumulated the highest number of replies were June 2019 (7.2%), August 2019 (6.3%) and February 2020 (5.8%). In the period after confinement, the months with the highest rate of replies were August (4.8%) and September (6.1%) 2020, and March 2022 (5.7%) (Tables 2 and 3).

Retweets increase considerably in some months. The first highlight occurs before Covid-19, specifically in March 2018 (Table 2). The most retweeted tweet (4915 retweets in March 2018) was posted by @Profe_RamonRG and dealt with the importance of qualitative assessment, highlighting the importance of the students’ qualities and emotional education. The second highlight appears after Covid-19, specifically in the months of confinement and state of alarm ( Table 3).

Interactions before Covid-19

Interactions after Covid-19

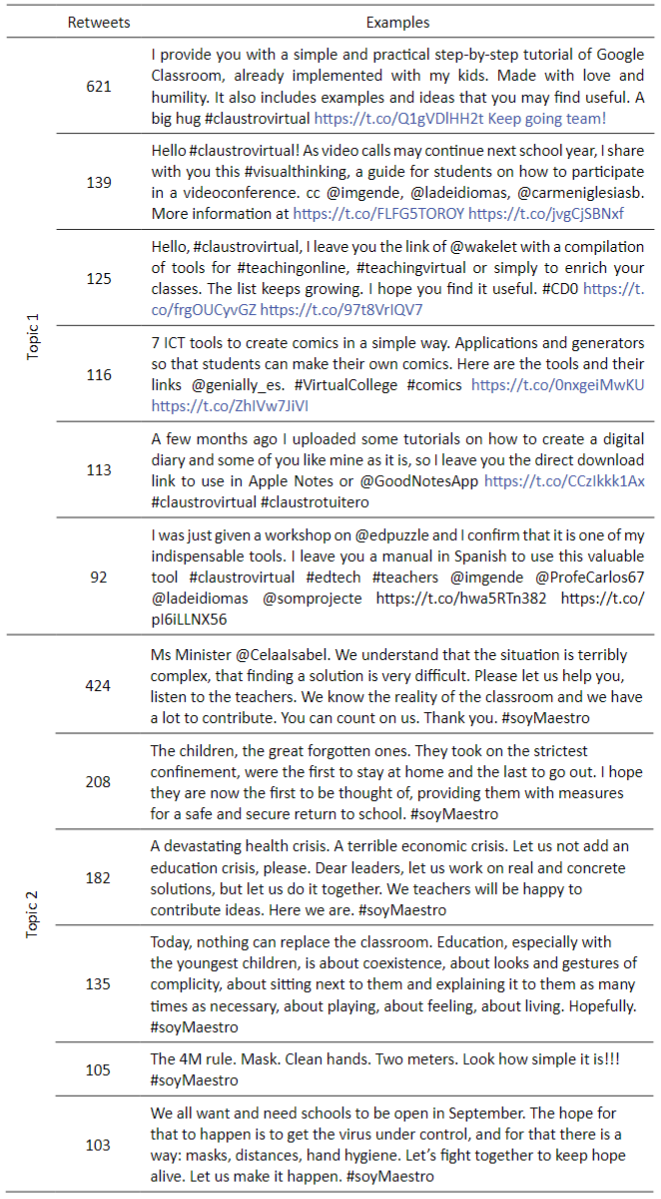

The qualitative analysis with Atlas.ti of the content of the most retweeted tweets in this highlight shows that they are related to the exchange of teaching resources in the digital space, but also to the consequences of the pandemic and the school conditions that will exist when the pandemic allows a return to the classroom (Table 4). These issues coincide with the topics found in response to research question 2 for this period.

Examples of the most retweeted tweets

Finally, likes (which is another way for teachers to interact and take interest in their colleagues’ contributions) have increased significantly in the months following confinement (Figure 2). The most retweeted tweets also accumulate more likes, so retweets and likes have a direct relationship.

Figure 2

Retweets, replies and likes before and after Covid-19

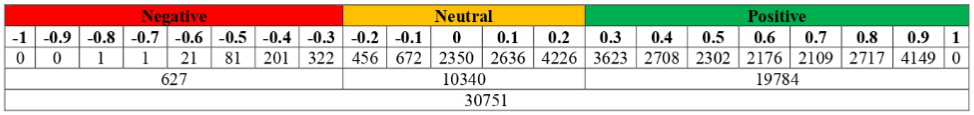

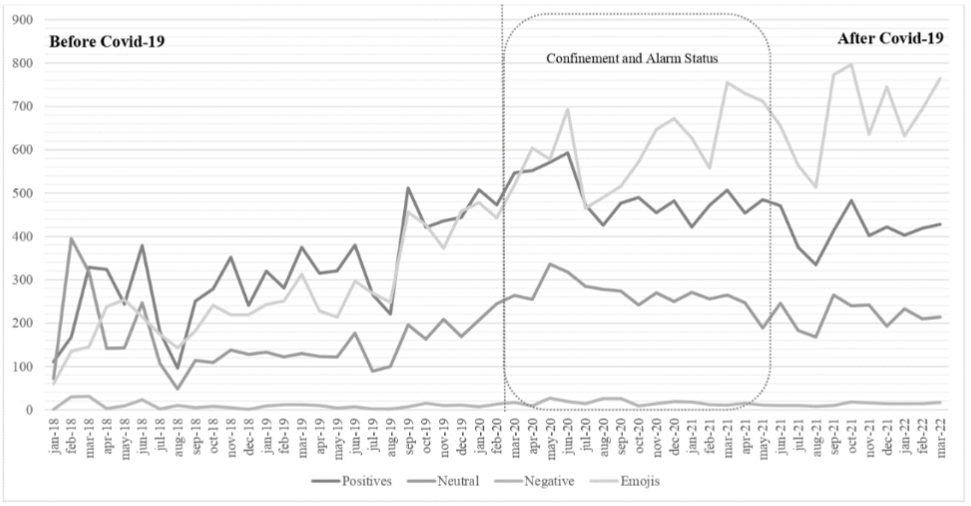

RQ4. How did teachers’ feelings on Twitter evolve before and after Covid-19?

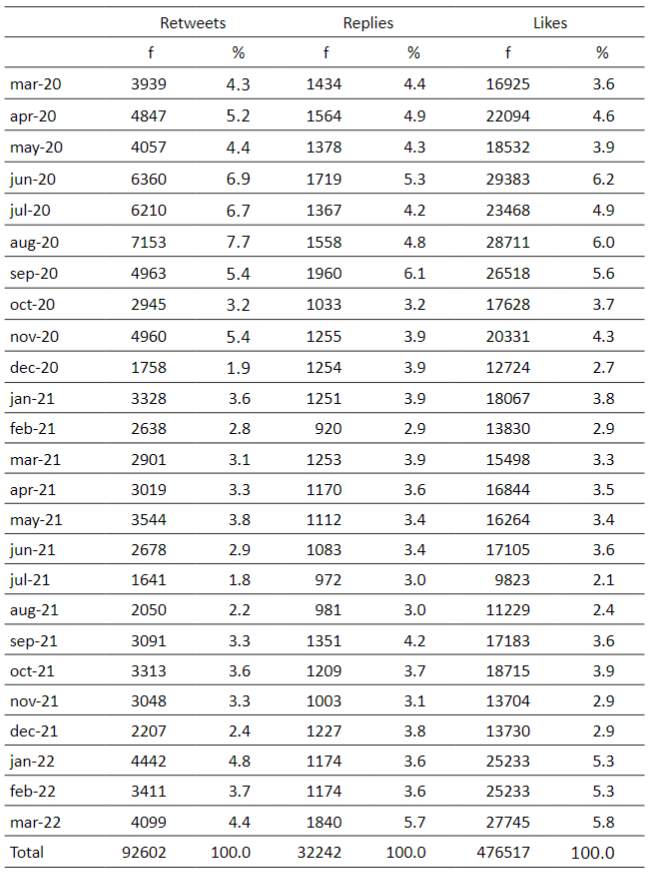

To answer the fourth research question, we first performed SA (figure 3). The results show a positive polarity of the emotional content in 64.3% (n=19784) of the tweets analysed; 33.6% (n=10340) of the tweets have neutral emotional content; finally, only 2.1% (n=627) of the total sample have negative result in the sentiment analysis.

Figure 3

Google’s Natural Language API SA results

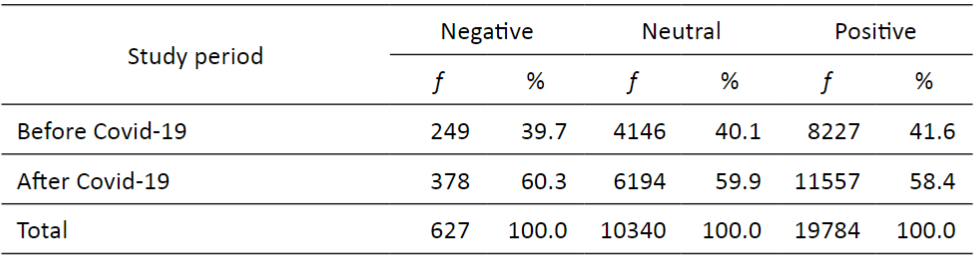

After Covid-19, our analysis shows a very significant increase in the emotional content of tweets, around 20% more than in the pre-pandemic period (table 5). This increase is independent of sentiment polarity and is found in tweets with positive, negative and neutral emotional content. Sentiment polarity is similar in the two periods, although emotional content is intensified.

Sentiment polarity before and after Covid-19

The visual SA analysis of the sample resulted in the use of a total of 1089 different emojis. Of these 1089 emojis, only 29 of them appeared with a repetition of more than 100 times, predominantly emojis with a positive emotional charge, as classified by Fernández-Gavilán et al. (2018) and Chen et al. (2018). The comparison by period is consistent with the sentiment analysis above. The emotional content of tweets reflected in emojis increased in the post-Covid-19 period, with a particular incidence of emojis expressing positive sentiment (Figure 4).

Figure 4

SA and emojis before and after Covid-19

Qualitative content analysis with Atlas.ti identified four themes in tweets with positive sentiment polarity and five themes in tweets with negative sentiment polarity.

The themes linked to positive feelings are related to autonomous learning (Especially the teachers, who have been able to adapt to this challenge of teleteaching, even with all the difficulties encountered, have been and are still there at the helm), the development of digital competences (By the way, I am not an isolated case. Like me, thousands of teachers are giving digital competence a go these days), and the acquisition of resources for the classroom (I’m thinking of getting an #instagram account as a teacher to find even more resources. Would you recommend it?).

Tweets related to the commitment of the education community also show positive sentiments ( It was teachers, students and their families who saved education, once again. Others will claim medals, and we give them away, because we never did it for medals, we are driven by an unwavering commitment to our students. That is how it has always been).

The tweets with negative sentiments were about frustration with the difficulties of online teaching (After another hard week full of difficulties, after the anguish of seeing how they keep getting confined every day, and with the terrible wear and tear of it all, getting to Friday means too much. Hopefully this weekend will repair some of the damage), the lack of technological resources (What about those thousands of teachers who don’t have Google Classroom, Moodle, Teams and other private or official platforms? I keep seeing talks, webinars, meetings... and I don’t hear anyone talking about this other reality), as well as problems related to the use of digital platforms (Not with your data (or mine), privacy in times of pandemic and beyond. Are teachers aware of the responsibility to comply with the RGDP? And what about management teams, families and students?).

Finally, the political management of education in the pandemic is associated with very negative feelings (Since the minister does not say it, I will say it: thank you #claustrovirtual, to my future colleagues, for having adapted to the situation autonomously, without indications or help) (The equation is simple if you have the will. But it is easier to leave the problem to teachers. It would not be unusual for them to take advantage of the autonomy of the school, without giving resources. Then, if it goes wrong, it is because we teachers are not trying hard enough).

DISCUSSION

This study examined how teachers in Spain tweeted and the impact Covid-19 had on this activity. The results provide information on the activity generated, the professional interests, needs and concerns, as well as the emotional or sentimental load that has been generated before and during Covid-19. We interpret these results by linking them to the existing literature in terms of flexible teachers’ community, continuous professional development and emotional support network.

Flexible teachers’ community

Twitter is an open and flexible space where you can interact at any time, from anywhere, as many times as you want. Our study provides new insights into the flexibility and adaptability of this social network as a space for teacher interaction, especially when teachers share and search for online resources, which is in concordance with Greenhow et al. (2021) study.

The freedom of access to flexible teacher communities on Twitter is evidenced by the increase in teacher tweets during the period of lockdown and state of alarm due to Covid-19 and the subsequent decrease in activity. Even during the school holiday period of the lockdown in Spain, teachers used Twitter more than in other years. This phenomenon has been extensively described in the literature in other countries. It is related to the uncertainty produced by school closures and the transfer of teaching-learning processes to the digital environment (Greenhow et al., 2021; Trust et al., 2020).

Our data also showed changes in how teachers interacted in teacher networks on Twitter after Covid-19. In particular, many teachers retweeted other interventions as a way of sharing content, with a notable increase during confinement in Spain. The possibilities of interacting on Twitter (beyond writing tweets) allow not only to develop the network but also to keep it active (Carpenter & Krutka, 2015; Carpenter et al., 2020).

Furthermore, our findings show how the content of interest to teachers changed according to the global context. Thus, as of March 2020, teachers in Spain tweeted to request and share digital resources to facilitate teaching in the new educational space (Zhou & Mou, 2022).

New themes emerged concerning virtual teaching and health measures to ensure a safe return to the classroom. This suggests a change in teachers’ needs and interests that was immediately reflected in teachers’ Twitter chats. Our findings show that a flexible network of teachers grouped around educational hashtags has formed in Spain, accessible at any time and from anywhere (Galvin & Greenhow, 2020; Greenhow et al., 2021), which adapts to new contexts quickly (Trust et al., 2016).

Continuous professional development

The literature has shown that Twitter is a social network that teachers use to collaborate, share experiences, train and establish new professional contacts (Carpenter & Krutka, 2015; Galvin & Greenhow, 2020; Greenhow et al., 2021; Willet, 2019). Our study has evidenced that teachers used Twitter to support their professional development, sharing and requesting digital resources that will help them reorganise online teaching caused by Covid-19. We agree with the study by Greenhow et al. (2021) that one of the reasons teachers use this social network is to overcome the limitations of local environments.

Since Covid-19, professional development through teacher communities on Twitter has increased very intensively in Spain. For example, our results show a five-fold increase in interest in technologies related to online teaching, and the sharing of programmes, tutorials, recorded lectures, etc. In particular, during the confinement in Spain, technological tools such as Genially, Wakelet, Flipgrid, Quiz and Canva, among others, were very relevant. This suggests a tendency to consider new ways of teaching as a result of the restrictions derived from the closure of schools (Rehm et al., 2021).

Our results identify a topic related to teachers’ professional activity that is not found in the literature. This is the teachers’ interest in occupational safety from Covid-19, which expresses concern on Twitter about a safe return to face-to-face teaching, access to face masks and the conditions of confinement. This issue has been studied extensively in other fields such as health (Menon et al., 2020; Michaels & Warners, 2020), but has not generated studies in the field of education.

Emotional support network

Our study shows that teacher communities on Twitter constitute a highly effective emotional support network. Our results revealed that teachers in Spain tweet and share positive emotional content before and after Covid-19, which is consistent with previous studies (Arora et al., 2021; Fernández-Gavilanes et al., 2018). The confinement situation was associated with increased emotional content in teachers’ tweets, regardless of the positive, negative or neutral polarity of the tweets. These results disagree with Zhou and Mou’s (2022) research, which reports an increase in negative sentiment in China over the same period.

The prevalence of positive feelings was independent of the topics covered. It appeared linked to both professional development (self-learning, digital competence development and virtual classroom resources) and adverse situations (confinement, de-escalation, safe return to the classroom, concern about disease). This suggests that writing, reading and sharing tweets became a very important emotional support mechanism in teachers’ networks.

These findings are consistent with other studies that indicate that teachers use Twitter as a space in which to experience emotional support from a professional learning community (Trust et al., 2018; Xing & Gao, 2018).

Although negative emotional content is the least frequent, the increase in the period of confinement of negative feelings related to the technological difficulties of online education and the political management of the educational consequences of Covid-19 is significant.

Although not an objective of our study, our results suggest that the historical Twitter archive is a valid resource for the analysis of teachers’ sentiments in longitudinal research that includes the Covid-19 period, as demonstrated by Harron and Liu (2022).

Limitations

Among the limitations of this study, we can point out our sampling decision, which focuses on Spanish teachers. Future research can expand the sample to include teachers from different Spanish-speaking countries to allow a comparative study. Another limitation of the study is that a mainly quantitative approach based on public data mining and sentiment analysis was used to examine professional networks. Although qualitative content analysis was used to answer some research questions, it would be valuable to use other qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups to obtain more detailed information about teachers’ concerns and interests in social networks.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that Spanish teachers use social networks for professional development and emotional support and that this trend has increased during Covid-19. The use of Twitter increased during the confinement period and the state of alarm due to Covid. Our results show that teachers’ motivations to use digital technologies in their teaching practice increased during the pandemic. Consequently, we can affirm that in emergency situations, Twitter facilitated the creation of flexible and effective professional networks of teachers, which were formed around educational hashtags. The notable increase in retweets as a form of content sharing during confinement reinforces the conclusion that strong and sustained networks were established to deal with the situation of uncertainty in the educational context. Specifically, teachers in Spain tweeted to request and share educational resources, and to address issues related to virtual teaching and health measures being implemented in the school environment.

In addition, the technological tools most used before and after Covid-19 by teachers in Spain have been identified, which favours the development of future informal learning initiatives in digital spaces. The main resources referred to on Twitter for managing e-learning were Genially, Wakelet, Flipgrid, Quiz, and Canva. These results are an indicator of the kind of information and resources teachers are looking for in a crisis like Covid-19, which is useful for action in similar scenarios.

Twitter was not only used as a professional network, but this study also shows that emotional support networks were built among teachers, characterised by positive emotional content, although negative emotional content related mainly to technological difficulties and political management of the pandemic also increased during confinement.

Our findings do not simply describe the issues that matter to teachers but highlight how the context implies change and how this influences continuing professional development. This information will enable us to provide comprehensive coverage for teachers, involving professional, emotional, and political support.

REFERENCES

Arora, A., Chakraborty, P., Bhatia, M. P. S., & Mittal, P. (2021). Role of emotion in excessive use of Twitter during COVID-19 imposed lockdown in India. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 6, 370-377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00174-3

Beardsley, M., Albó, L., & Aragón, P. (2021). Emergency education effects on teacher abilities and motivation to use digital technologies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1455-1477. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13101

Carpenter, J. P., & Krutka, D. G. (2015). Engagement through microblogging: Educator professional development via Twitter. Professional Development in Education, 41(4), 707-728. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.939294

Carpenter, J. P., Trust, T., Kimmons, R., & Krutka, D. G. (2021). Sharing and self-promoting: An analysis of educator tweeting at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers and Education Open, 2, Artículo 100038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2021.100038

Carpenter, J., Tani, T., Morrison, S., & Keane, J. (2020). Exploring the landscape of educator professional activity on Twitter: An analysis of 16 education-related Twitter hashtags. Professional Development in Education, 48, 784-805. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1752287

Chen, Y., Yuan, J., You, Q., & Luo, J. (2018). Twitter sentiment analysis via bi-sense emoji embedding and attention-based LSTM. MM’18: Proceedings of the 26th ACM International Conference on Multimedia Seoul (pp. 117-125). Republic of Korea.

Del Olmo, E., & Arias, I. (2021). An empirical study with sketch engine on the syntactic-pragmatic interface for the identification of thematic structure in Spanish. Revista de Humanidades Digitales, 6, 129-150. https://doi.org/10.5944/rhd.vol.6.2021.30965

Fernández-Gavilanes, M., Juncal-Martínez, J., García-Méndez, S., Costa-Montenegro, E., & González-Castaño, F. J. (2018). Creating emoji lexica from unsupervised sentiment analysis of their descriptions. Expert Systems with Applications, 103(1), 74-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2018.02.043

Firoozeh, N., Nazarenko, A., Alizon, F., & Daille, B. (2020). Keyword extraction: Issues and methods. Natural Language Engineering, 26(3), 259-291. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324919000457

Galvin, S., & Greenhow, C. (2020). Educational networking: A novel discipline for improved K-12 learning based on social networks. En A. Peña-Ayala (Ed.), Educational networking: A novel discipline for improved learning based on social networks (pp. 3-41). Springer.

Gao, F., & Li, L., (2017). Examining a one-hour synchronous chat in a microblogging-based professional development community. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 332-347. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12384

Gee, J. P. (2017). Affinity spaces and 21st century learning. Educational Technology, 7(2), 27-31.

Gómez, M., & Journell, W. (2017). Professionality, preservice teachers, and Twitter. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 25(4), 377-412.

Greenhalgh, S. P., Rosenberg, J. M., & Russell, A. (2021). The influence of policy and context on teachers’ social media use. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(5), 2020-2037. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13096

Greenhalgh, S. P., Rosenberg, J. M., Willet, K. B. S., Koehler, M. J., & Akcaoglu, M. (2020). Identifying multiple learning spaces within a single teacher-focused Twitter hashtag. Computers & Education, 148, Article 103809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103809

Greenhow C., Staudt Willet K. B., & Galvin S. (2021). Inquiring tweets want to know: #Edchat supports for #RemoteTeaching during COVID-19. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1434-1454. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13097

Harris, A. (2020). COVID-19–school leadership in crisis? Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), 321-326. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0045

Harron, J., & Liu, S. (2022). Tweeting about teachers and COVID-19: An emotion and sentiment analysis approach. En E. Langran (Ed.), Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 1502-1511). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, R. (2018). Public internet data mining methods in instructional design, educational technology, and online learning research. TechTrends, 62, 492-500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0307-4

Li, X., Zhang, J., Du, Y., Zhu, J., Fan, Y., & Chen, X. (2022). A novel deep learning-based sentiment analysis method enhanced with emojis in microblog social networks. Enterprise Information Systems, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17517575.2022.2037160

Luo, T., Freeman, C., & Stefaniak, J. (2020). “Like, comment, and share” professional development through social media in higher education: A systematic review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(4), 1659-1683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09790-5

Menon, A., Klein, E. J., Kollars, K., & Kleinhenz, A. L. W. (2020). Medical students are not essential workers: Examining institutional responsibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Academic Medicine, 95(8), 1149-1151. https://doi.org/10.1097/ ACM.0000000000003478

Michaels, D., & Warners, G. R. (2020). Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and worker safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA, 324(14), 1389-1390. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.16343

Neuendorf, K A. (2017). The content analysis guidebook. SAGE.

Nochumson, T. C. (2020). Elementary schoolteachers’ use of twitter: Exploring the implications of learning through online social media. Professional Development in Education, 46(2), 306-323. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1585382

Osorio, S., Peña, A., & Espinoza-Valdez, A. (2021). Systematic literature review of sentiment analysis in the Spanish language. Data Technologies and Applications, 55(4), 461-479. https://doi.org/10.1108/DTA-09-2020-0200

Parrish, C. W., & Martin, W. G. (2022). Cognitively demanding tasks and the associated learning opportunities within the Math Twitter Blogosphere. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 53(2), 364-402. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2020.1772388

Pokhrel, S., & Chhetri, R. (2021). A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 133-141. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631120983481

Quintana-Gómez, A. (2021). Análisis de los procesos de tratamiento de información en un estudio de análisis de sentimiento utilizando la tecnología de Google. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 154, 41-55. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.154.e1336

Rehm, M., Moukarzel, S., Daly, A. J., & Del Fresno, M. (2021). Exploring online social networks of school leaders in times of COVID-19. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1414-1433. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13099

Rosell-Aguilar, F. (2018). Twitter: A professional development and community of practice tool for teachers. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2018(1), 6. http://doi.org/10.5334/jime.452

Sailunaz, K., & Alhajj, R. (2019). Emotion and sentiment analysis from Twitter text. Journal of Computational Science, 36, Artículo 101003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2019.05.009

Scott, M. (1997). PC analysis of key words – And key key words. System, 25(2), 233-245. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(97)00011-0

Semingson, P., & Kerns, W. (2020). Categorizing and leveraging hashtag-based efforts to #Keeplearning and #Keepteaching with remote learning due to COVID-19. En Proceedings of EdMedia + Innovate Learning (pp. 115–119). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Trust, T., Carpenter, J. P., Krutka, D. G., & Kimmons, R. (2020). #RemoteTeaching & #RemoteLearning: Educator tweeting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 151-159.

Trust, T., Krutka, D. G., & Carpenter, J. P. (2016). “Together we are better”: Professional learning networks for teachers. Computers & Education, 102, 15-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.06.007

Willet, K. B. S. (2019). Revisiting how and why educators use Twitter: Tweet types and purposes in #Edchat. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 51, 273-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2019.1611507

Xing, W., & Gao, F. (2018). Exploring the relationship between online discourse and commitment in Twitter professional learning communities. Computers & Education, 126, 388-398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.010

Zhou, J., & Ye, J. (2020). Sentiment analysis in education research: a review of journal publications. Interactive Learning Environments, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1826985

Zhou, M., & Mou, H. (2022). Tracking public opinion about online education over COVID-19 in China. Education Tech Research Dev, 70, 1083-1104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10080-5

Received: 21 September 2022

Accepted: 24 February 2023

Published: 13 June 2023