1. INTRODUCTION

The aim of this paper is twofold. Firstly, to explore how Corpus Linguistics (CL) collocational methods may be used to identify types of gender representation in the online press. Secondly, to encourage Digital Humanities (DH) researchers to combine the use of CL tools as well as visualization and exploration tools to process, analyze, summarize, and represent great amounts of information. In this work, an analysis of corpus-based data showing how women and men are represented linguistically is reported. The data crunching and statistical analysis would normally imply a subsequent loss of sensitive information, but by complementing data extraction and analysis with network graphs, many lexical relationships difficult to observe when the data is represented in statistical terms can be identified. As the use of CL methods and tools is mostly circumscribed to linguistic studies, we believe this combination may be put to use in DH to expand research methods even further.

Anchored in the Humanities, gender studies provide researchers the opportunity to explore identities and subcultures, cultural geographies, LGBT and queer studies, digital media, and gender and cultural norms. The idea of focusing on the news is also rooted in the Humanities and one example of this is the work done by literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin (1981), who emphasized the notion of looking at the news in terms of voice, arguing that texts are formed by a variety of voices. Another example we could mention is A History of Women in the West (1992), the project directed by Georges Duby and Michelle Perrot (Fraisse & Perrot, 1993; Klapisch-Zuber, 1992; Schmitt Pantel & Pastor, 1991; Thébaud, 1993; Zemon Davis & Farge, 1992). Published in the early 1990s, this monumental project traces the roles of women from ancient history to the twentieth century. Thirty years later one could argue that these prototypical Humanities projects might nowadays benefit from diachronic corpus analysis, analogous to the one presented in the following pages. Research using and addressing news as a source of inquiry have been conducted (Montgomery, 2007; Bednarek, 2016), as in CL the use of digital news for corpus building is prevalent (Baker et al., 2013; Baker, 2010a).

Despite advances in Gender Studies research, gender is still considered a binary categorization. Such social categorization contributes to the formation and persistence of gender stereotypes and reinforces perceptions of differences between men and women.

Violence is one of the most important problems facing society today. The violence that permeates all areas of society not only fosters physical aggression but also desensitizes a large part of society. Violence exists in the psychological sphere as well as in the social sphere, where it is reflected in the beliefs and ideology of some members of society who justify mistreatment and aggression to the point of naturalizing them. Consequently, ordinary citizens, the media, and social institutions perpetuate language that justifies violence. It is not unreasonable, therefore, to use linguistic knowledge to unmask sexist language justifying gender representations, stereotypes, or even violence against certain social groups. One of the most vulnerable groups in this regard is women. Mexican society, for example, is becoming aware not only of the disproportionate number of femicides but also of the sexist and misogynist substratum that acts as a breeding ground for discrimination, oppression, and death. Women, unwilling to suffer violence on a day-to-day basis have recently taken to the streets, workplaces, and schools to expose the violence they are subjected to. Given the above, this paper reports the collocational behavior of the lemmas hombre (man) and mujer (woman) in an online press corpus in Spanish.

2. CORPUS LINGUISTICS AND DIGITAL HUMANITIES

Digital media data has expanded exponentially, and it is the object of study in disciplines such as Sociology, Communication, Psychology, and Linguistics. In terms of CL, its reach extends beyond its disciplinary confines, with corpus approaches notably applied to research in subjects including but not limited to Anthropology (Nolte et al., 2018), Geography (Gregory et al., 2015), History (McEnery & Baker, 2016), Literature (Biber, 2011) and Translation Studies (Laviosa, 2002). There are other areas such as Medicine, Business, Law, and Data Science, which also rely on digital information as a source of data to conduct research. When doing so, all these disciplines rely on language as a vehicle to study their subject matter. CL has a central role in this new genre.

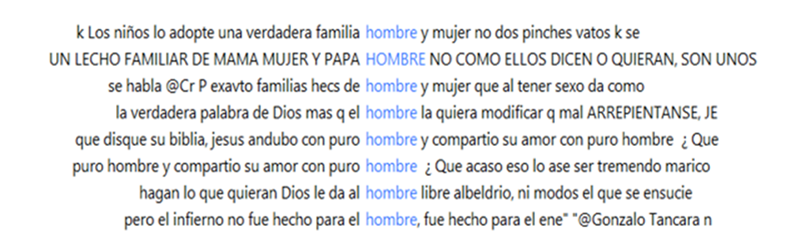

CL focuses on a set of procedures or methods for studying language. Corpora, the main source of data in CL, can comprise millions of words, so to analyze such a large amount of information computer software is needed to search, retrieve, manipulate, and analyze it. Concordancers display all occurrences or tokens of a particular type in a corpus. Figure 1 shows what a concordance sample looks like:

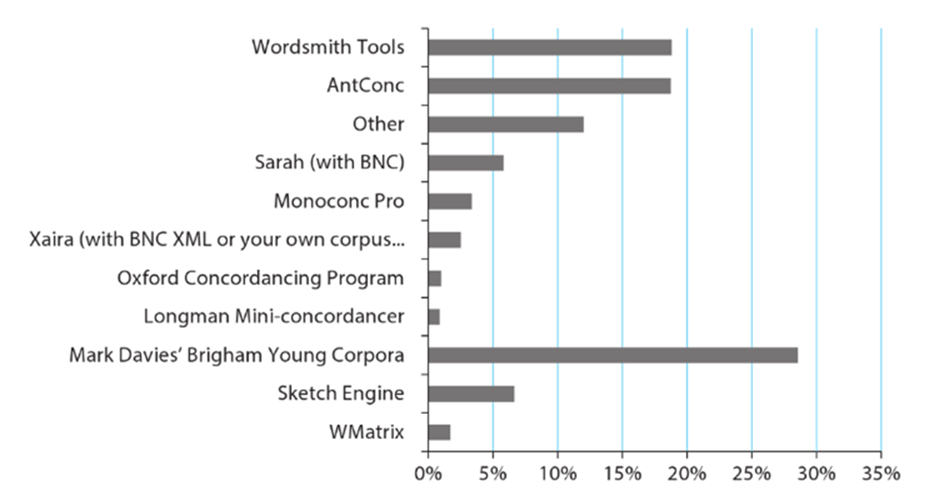

Some third-generation concordancers are WordSmith (Scott, 1996), MonoConc (Barlow, 1999), and AntConc (Anthony, 2005). They allow analysis with the following tools: frequency lists, n-grams, collocation, and keywords. However, rather than merely expanding corpus analysis tools, fourth-generation concordancers focus on addressing issues such as the limited power of desktops, problems arising from non-compatible PC operating systems, and legal restrictions on the distribution of corpora (McEnery & Hardie, 2011). Some of the most important web interfaces are the Brigham Young University (BYU) corpus family (Davis, 2020), CQPweb (Hardie, 2020), and SketchEngine (Kilgarriff, 2020). One of the greatest differences between third and fourth-generation concordancers is that in the former a corpus needs to be uploaded whereas in the latter the concordancers themselves provide users with several corpora for them to research according to their needs. This study relied on the BYU fourth-generation concordancer to query the NOW corpus. Figure 2 shows some of the most common concordancers.

Since CL is usually employed as a method framework and is technology mediated, it can assist DH as a methodological approach. Research in DH done with Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Computational Linguistics skills and tools exists, but unlike NLT and computational linguistics, CL does not require programming skills, which makes CL more accessible to researchers not familiarized with language programming.

DH researchers may benefit from CL methods and tools because they can help them examine digital data in their areas of expertise. By considering how data is collected and analyzed in CL, and given the potential of its tools, DH can look at data from a different perspective and explore new avenues in different research areas.

3. PREVIOUS RESEARCH

The use of collocational analyses as a research method on how women and men are linguistically represented in Spanish has not received sufficient attention. Few studies have been found related to this type of research (Castillo, 2019; Alochis, 2016). This is in strong contrast to the wealth of studies on the linguistic representation of both women and men in English, as language and gender studies have a relatively long history in linguistics. Research in this area ranges from stating that the differences in how women and men use language are due to linguistic deficits on the part of women to differences attributed to the idea that gender is a social construct (Litosseliti, 2014; Coates, 2015; Kendall & Tannen, 2015; Flowerdew & Richardson, 2017; Weatherall, 2005). A significant amount of linguistic research has adopted both a descriptive and qualitative approach and has focused on analyzing how men and women use language, but little attempt has been made to examine how men and women are linguistically represented. In the last 20 years, CL has been instrumental in the development of language and gender as a field of inquiry. The approach to researching language and gender has shifted, in part, from using small sets of data to the use of large amounts of data comprising millions of words and has incorporated the use of corpus query tools to investigate how people are discursively represented. In the last decade, there has been extensive research in CL addressing how women and men are linguistically represented in different corpora (Baker, 2010b, 2012; Caldas-Coulthard & Moon, 2010; Moon, 2014; McEnery & Baker, 2015); however, gender linguistic representation has been conducted mostly in English and it is relatively unexplored in Spanish. This study is an attempt to expand research in this area by using CL tools and methods to explore the press in Spanish.

Through collocational analysis, Romaine (2000) used the Brown Corpus to conduct a frequency analysis to investigate neutral terms such as chairperson. In a three-million-word sample she found that chairman occurred 1,142 times, chairperson appeared 130 times, and chairwoman was used only 68 times. She suggested that chairperson had become a marked term in opposition to chairman, which remains the unmarked androcentric term (Romaine, 2000, p. 130). In the same study but based on the British National Corpus (BNC), a collocational analysis of doctor (which could refer to either a man or a woman) showed that lady doctor occurred 125 times, woman doctor appeared 20 times and female doctor occurred 10 times, whereas there were no occurrences of gentleman doctor, one occurrence of man doctor, and 14 of male doctor. In the same way, family man appeared 94 times whereas family woman appeared only four times. Such discrepancies were attributed to the idea that only men had careers and that women who did so should be marked; in line with this thought, she added that a man could be a family man, but it would be odd to call a woman a family woman based on the assumption that women are by definition family women (2000, p.117). By querying the Brown Corpus, the Lancaster-Oslo-Bergen Corpus (LOB), the Wellington Corpus of New Zealand English (WWC), the Freiburg-Brown Corpus of American English (Frown), and the Freiburg-LOB (FLOB) Corpus of British English, Sigley and Holmes (2002) reported that the frequency of sexist suffixes such as -ess and the pseudo-polite terms lady/ladies, whether by themselves or as part of occupational terms (cleaning lady), had declined since the 1960s. It was moreover noted that the use of man as a generic term had also declined in written material and that the use of male and female as gender premodifiers (female lawyer) had declined as well. The findings also showed that while man and men decreased significantly, the frequency of women and woman doubled, and that woman was far less used than women.

By employing a keyword and collocation approach to explore stereotypical constructions of age and aging, Mautner (2007) queried the 500-million-word Bank of English Corpus to examine the keyword elderly and found that it collocated 75 times with woman, 35 times with women, 37 times with lady, and 7 times with widow; in turn, man collocated 51 times with elderly and only 13 times with gentleman. Mautner found that elderly is a social rather than a chronological label and that women are associated with discourses of care, disability, and sickness. In a similar study, Pearce (2008) also found that some verbs denoting physical strength and the exercise of power such as dig, climb, jump, conquer, dominate and lead collocated with man, and no similar collocations were identified with woman. When those same lemmas were used as objects, it was found that verbs such as apprehend, arrest and convict, with legal connotations, collocated with man but not with woman; furthermore, as for collocations denoting “being victims of violence,” verbs such as kill, wound, knife and shoot collocated with man, whereas assault, gag, rape and violate collocated with woman.

In a more recent study, Moon (2014) analyzed English adjectives used to describe women and men with regards to age factor; by querying the Bank of English corpus, the results showed that the most common collocates of young man/men were handsome, nice, bright, tall and angry. Other collocates that occurred six or more times were related to the relationship domain (gay, single, married, lonely, bisexual, etc.) and physical (tall, thin, muscular, slender, etc.). Concerning the collocations of middle-aged woman/women, there were fewer adjectival collocates; some of these were single, lonely, plump, fat, stout, tall, thin, elegant, attractive, beautiful, bored, and healthy among others; some of these collocates are positive in evaluative orientation but there are some that seem to suggest negative traits for women in midlife. One of the latest contributions to this research area was that of Baker (2010b). By employing the Lancaster corpus (BLOB), the LOB, the FLOB, and the British English 2006 (BE06) whose construction years are from 1931, 1961, 1991, and 2006 respectively, he undertook a diachronic study to analyze gender-marked language. Male and female pronouns, the lemmas man, men, woman, women, boy, girl as well as gender-related professions and terms of address such as Mr. and Ms were queried. The results showed a decrease in masculine pronouns while feminine pronouns showed a slight increase; however, despite this fluctuation, it was noted that the gap between the use of masculine and feminine pronouns was still substantial. As for the use of inclusive terms by presenting both alternatives such as him/her, s/he, he/she, he or she and him or her, the data showed that their use increased between 1961 and 1991 but the total for 2006 is less than half than in 1991. This suggested, according to Baker, that this strategy of using inclusive terms did not gain ground and could even die out eventually. The analysis also showed that the noun spokesman appeared 1, 22, 50, and 43 times in BLOB, LOB, FLOB, and BE06 respectively; this seemed to imply a consistent use in the last 15 years. The word spokeswoman did not occur in BLOB and LOB but it occurred in FLOB and BE06 8 and 5 times, respectively; spokesperson did not occur in the BLOB and LOB but it appeared 2 and 4 times in the FLOB and BE06 respectively.

What these studies have in common is that their findings showed that men are linguistically represented more favorably than women; furthermore, most of the lemmas associated with maleness seem to remain as androcentric mark terms. This study investigates whether similar findings can be found in Spanish.

4. CONTEXT

Very present in public discourse is gender violence crushing communities across México and, in general, across Latin America. In its 2016 Mortality Statistics, the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and informatics (INEGI) in Mexico, reported that of the 46.5 million women aged 15 or older in the country, 66.1% (30.7 million) have been the victims of various types of violence at some point in their lives. Furthermore, 20.8 million women (44.8%) stated that at least one of these aggressions occurred within the 12 months prior to the interview conducted to obtain such results. The report also showed that 10.8 million women were subjected to some type of intimidation, harassment, bullying, or sexual abuse. Based on these statistics, it could be argued that violence against women is a problem of great proportions and a widespread social practice throughout Mexico since two-thirds of women over 15 have experienced labor discrimination and at least one act of emotional, physical, sexual, economic, or patrimonial violence. Furthermore, such acts of violence have been exercised by different aggressors, be it a partner, the husband or boyfriend, a family member, a fellow student or coworker, a school authority, a friend, a neighbor, an acquaintance, or a stranger. Table 1 shows the different kinds of violence women in Mexico are usually subjected to.

Table 1. Total prevalence of violence against women aged 15 and over1, by reference of the period, according to the type of violence2. Source: National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Informatics (2016b).

Violence against women does not stop and seems to be increasing due to lack of interest on the part of the authorities and society. The statistics provided by INEGI are alarming. When reviewing deaths by homicide that occurred in the 1990-2018 period, the number of women who died from intentional assaults between 1990-1994, 1995-2000 and 2001-2006 were in the order of 7,600 to 8,500. However, the murder of more than 12,000 women was recorded between 2007-2012, reaching 17,434 between 2013-2018, an increase of 60% with regards to 2001-2006. In the first quarter of 2022, through its National Urban Public Safety Survey, INEGI reported that 71% of women considered their city unsafe.

The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) reports that 14 of the 25 countries in the world where most femicides are committed (statistics from 221 countries are monitored) are in Latin America and the Caribbean; statistical evidence shows that femicide violence has continued to grow despite awareness campaigns (Garcia, 2018).

Taking into account that gender violence is a problem of great proportions that affects the daily lives of women, it is important to disclose how violence and misogyny are reflected in language used in the media.

In Mexico, the General Law on Women's Access to a Life Free of Violence (2007) states that there are five types of violence against women: (physical, sexual, psychological, economic, and patrimonial violence) and also considers five violence environments (family, community, labor, educational and institutional). This law recognizes verbal violence but does not quantify it statistically. It is clear that much of this violence is exerted both orally and in writing. This work exemplifies how corpus linguistics methodology can be used for research in DH.

5. METHOD

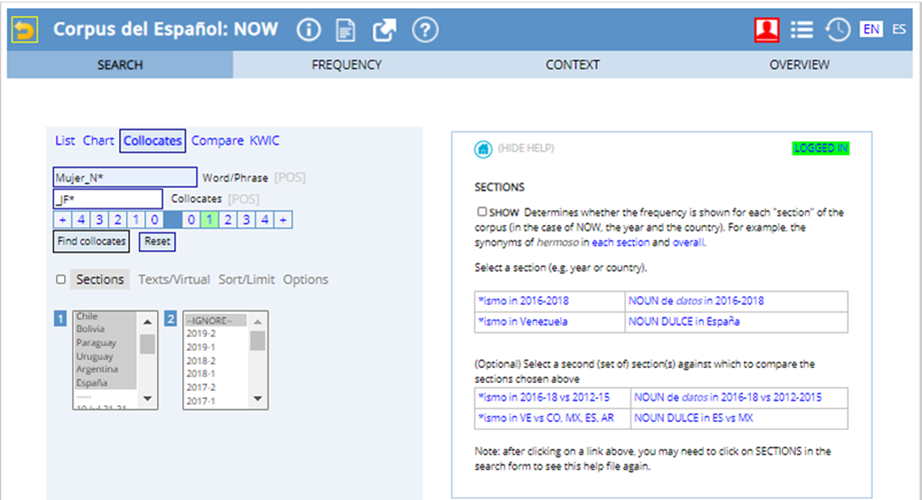

In this investigation, the Spanish News on the Web (NOW) corpus (Davis, 2020) was queried to explore how women and men are represented linguistically in the press. The collocations for woman and women as well as for man and men were searched with a window span of one space to the right and one to the left; in other words, collocates located immediately before and after the node word (lemma). Additionally, web-based news articles and newspapers from 2012 to 2018 in Latin American countries and Spain were searched. Adjectives with mutual information (MI) above 4 were retrieved. MI information is an association measure with a background in Information Theory (Manning & Schütze, 1999); thus, based on the information-theoretic notion of mutual information, an MI-score assesses the extent in which two words co-occur (Evert, 2008, p. 1229). MI highlights the rare exclusivity of collocation relationships, favoring collocates that occur almost exclusively in the company of the node, even though this may appear only once or twice in the entire corpus (Brezina, 2018, p. 71). An MI above 3 is considered statistically significant.

Figure 3 shows the interface of the NOW corpus in which the parameters are entered; it only shows the parameters entered to find the collocates to the right of the lemmas.

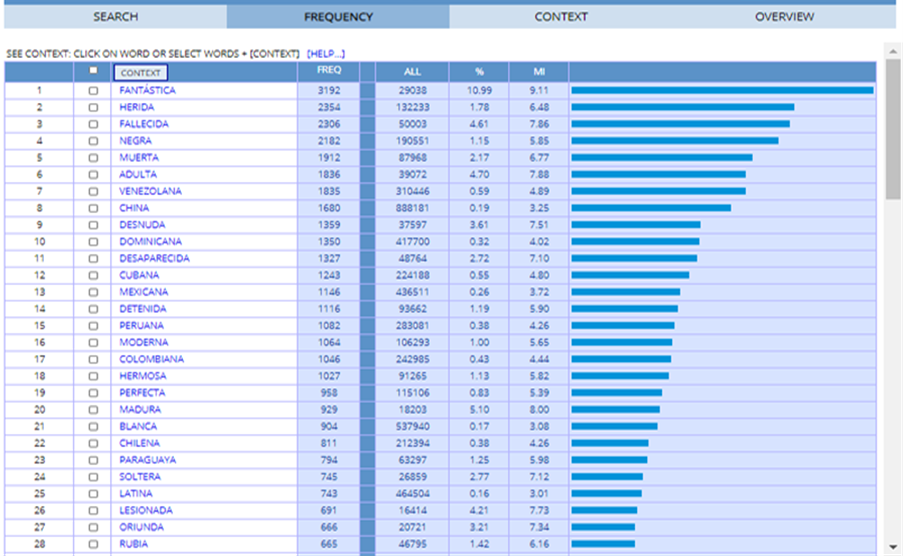

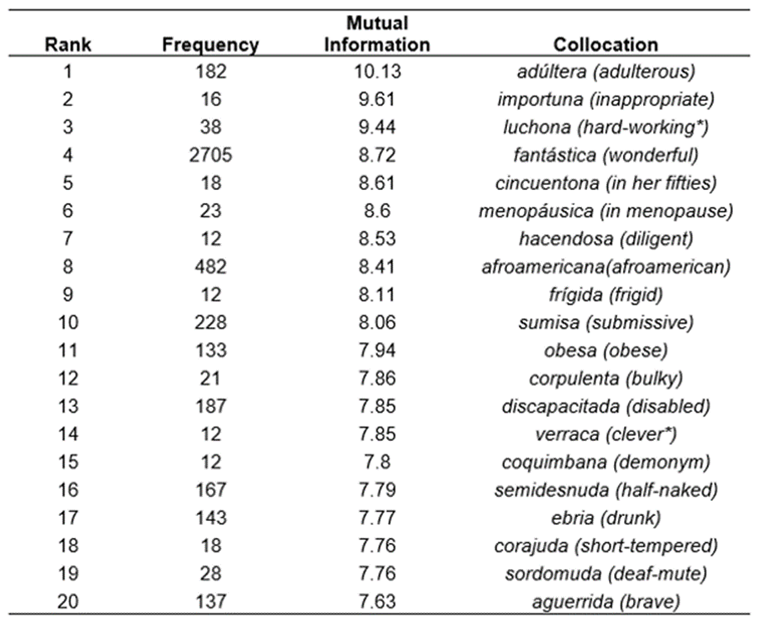

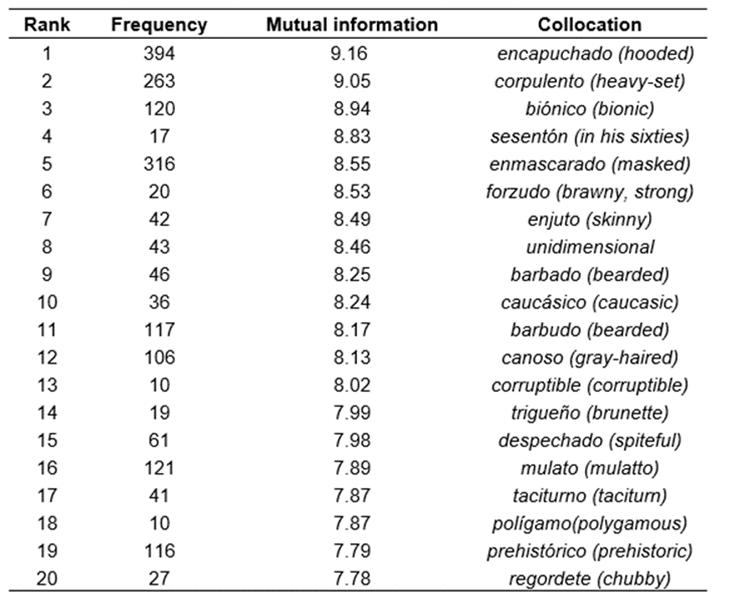

Every lemma was searched with the same parameters. Figure 4 shows some of the results for the search of the adjectival collocations of mujer (woman). The collocations with the highest MI appear at the top of the list.

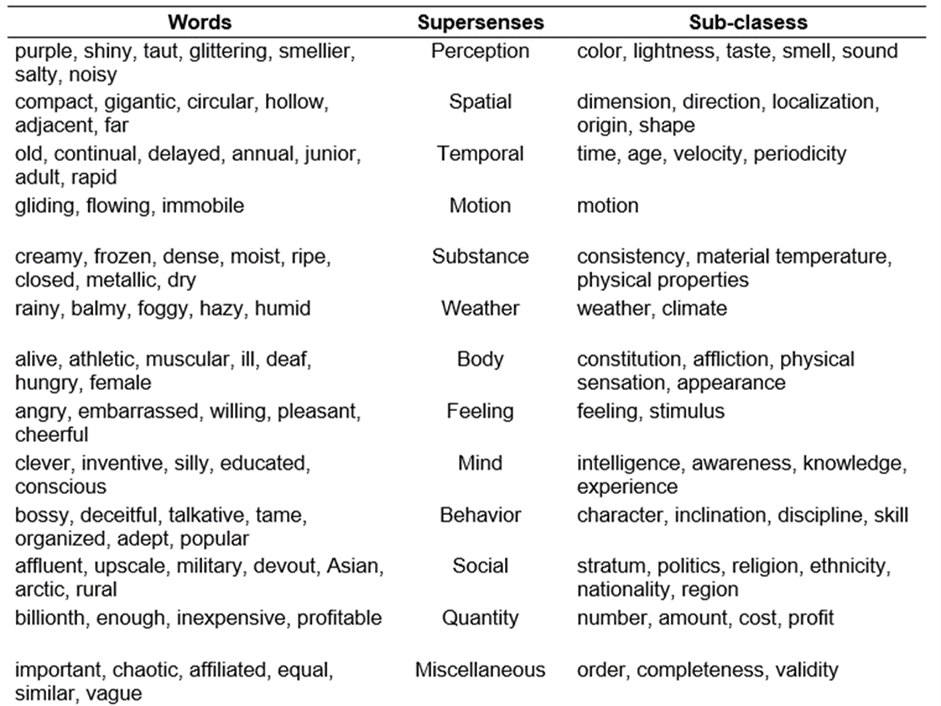

The following preprocessing stage involved the manual classification of adjectives into several categories to carry out a linguistic analysis that could reveal how men and women are linguistically represented in the Spanish-speaking press. The 'Supersenses Taxonomy' (Tsvetkov et al., 2014), which comprises thirteen coarse semantic classes followed by more fine-grained subcategories, was used to classify the adjectives.

Several taxonomies were considered for this research study. Two of them were Dixon’s (2010) adjective classification, which contains seven semantic types (dimension, physical property, color, human propensity, age, value, and speed), and Fellbaum (1998) English WordNet model, dividing adjectives into two classes; on the one hand, ascriptive adjectives, which enter into clusters based on antonyms and synonyms, and on the other hand, nonascriptive adjectives, which are similar to nouns used as modifiers. Both of these taxonomies were used but were not adequate for classification of adjectives in Spanish. A word of caution is necessary here concerning the use of taxonomies to classify adjectives. No taxonomy is flawless, and this is relevant when classifying adjectives that may convey idiosyncratic cultural traits. Considering the English WordNet, adjectives are organized in clusters that consist of a core synset (cluster of similar word meanings) and linked synsets with closely related meanings; however, there is no systematic organization connecting these clusters. An example of this involves the adjectives exasperated and cheesed off, listed as synonyms; nothing in this model indicates that they describe emotional states. Also, the distinction between ascriptive and nonascriptive adjectives is complicated by the fact that some adjectives can be both: nervous has an ascriptive sense in a nervous person, but not in a nervous disorder.

During the process of classifying adjectives, many were problematic for the taxonomies just mentioned. Given the above, a coarse sense taxonomy was needed to classify the hundreds of adjectives collected for collocational analysis. The SuperSenses taxonomy was originally used for adjectives in GermanNet and once it was adapted to Spanish it proved to be a better tool, allowing for more consistent classification. The fact that the Supersenses categories also provide subclasses facilitated the classification; for example, the Perception and Mind categories may overlap but the subclasses were useful in the classification process. A final comment concerning taxonomies and in particular to Supersenses is that there are classes (constructs), such as Social and Behavior, which are complex and qualitative and may not account for all their different senses of the adjectives. Finding a perfect taxonomy is a futile endeavor. Based on all the above, and after considering several taxonomies, the Supersenses taxonomy proved to be the best alternative.

At this point, it is important to revisit the rationale behind the use of graphs to represent the information obtained in this study. From a humanistic perspective, a shortcoming in CL is that the meaning of data is sometimes lost among the statistics, mainly if the data is not approached reflexively. In this research, Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009), an open-source software, was used for network visualization. The graphs help identify the most important adjectives associated with each lemma but also help detect the relationships among the adjectives for similarities or differences. This approach allows progression from a mere identification of adjectives that collocate with each lemma to an approach in which a more in-depth collocation analysis is possible. Graphs reveal hidden patterns, discourses, and sexist language; and more importantly, such visual representation permits the analysis of textual data as a whole and not in an isolated manner. The process to represent the data in the graphs is as follows.

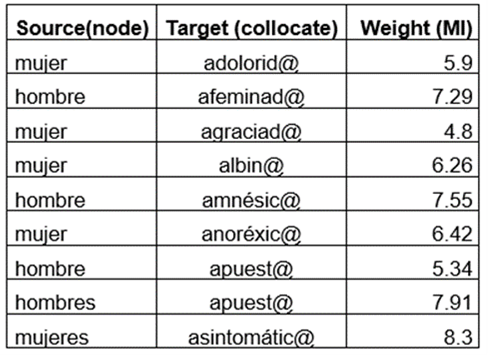

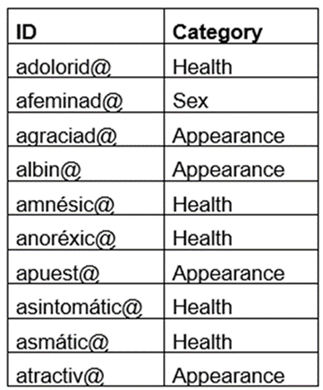

Firstly, adjectival lemmatization was carried out. This implies finding a headword (dictionary entry) for each adjective form. Adjectives in Spanish normally carry a gender morpheme (masculine or feminine) and a number morpheme (it works similarly in English: the plural is marked with an ‘s’ suffix and the singular form is unmarked). The lemmatization process can be performed via a lemmatizer, a computer program that removes morphemes and unifies tokens (individual words) under a headword. In Spanish, the lemmatization process simplifies the four options –for instance, grueso, gruesa, gruesos y gruesas (masculine singular, feminine singular, masculine plural, feminine plural of the word ‘thick’)– into the typically singular masculine form: grueso. In this paper the lemmatized form is written as grues@, with the @ symbol used as a suffix for neutral representation. Most PoS taggers (programs that attach grammatical information to words) contain a lemmatizer: free, easy to use options are TagAnt (Anthony, 2022) and Freeling (Padró & Stanilovsky, 2012). In this case, adjectival lemmatization was carried out with simple functions in a spreadsheet. Thus, a list of lemmatized collocations was obtained containing: node, collocate, and weight (mutual information, the stat showing association strength, as explained at the beginning of this section). This list is called the Edges list. A sample of the data is shown in Table 3.

Secondly, a list of nodes was created. It contains all types of words with a label referring to the adjective category involved (as described in section 6 below). A sample of this data is shown in Table 4.

These two lists were fed into Gephi as CSV (comma separated values) files. A Yifan Hu distribution was selected and the nodes were colored according to their category.

6. DESCRIPTION OF THE DATA

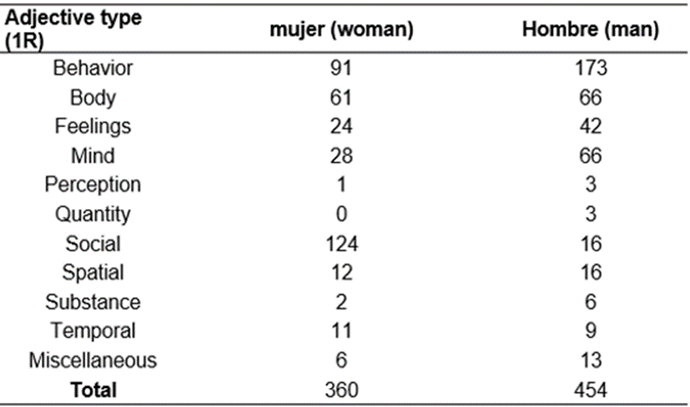

1,586 adjectival collocations with an MI above 4 were automatically extracted from the NOW corpus and manually classified according to the Supersenses classifications (Tsvetkov et al., 2014). Out of 1,586 collocations, 834 collocate with the lemma mujer, and from these 435 collocate with mujer (woman) and 399 with mujeres (women); the other 752 adjectives collocate with the lemma hombre and from these, 506 collocate with hombre (man) and 246 with hombres (men). In tables 5 and 6 only singular adjective types found one word to the right of the mujer (woman) and hombre (man) are shown.

Adjectival classification based on the “Supersense” category showed the following results. Lemmas in their plural form are not reported in Table 7.

7. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this section, the focus is on describing the lexical behavior of lemmas man and woman, but there is also an attempt to provide brief qualitative commentaries that can be revisited and expanded in future work. Comments in this section stem from the idea that social actors are judged as good or bad, loved or hated, admired or pitied, assessment based on the set of adjectives that denote such appraisal (Van Leeuwe, 2013). Journalists adopt stances toward both the material they present and the audience with whom they communicate (Martin & White, 2005). They approve and disapprove ideas, actions, or people based on their subjectivity.

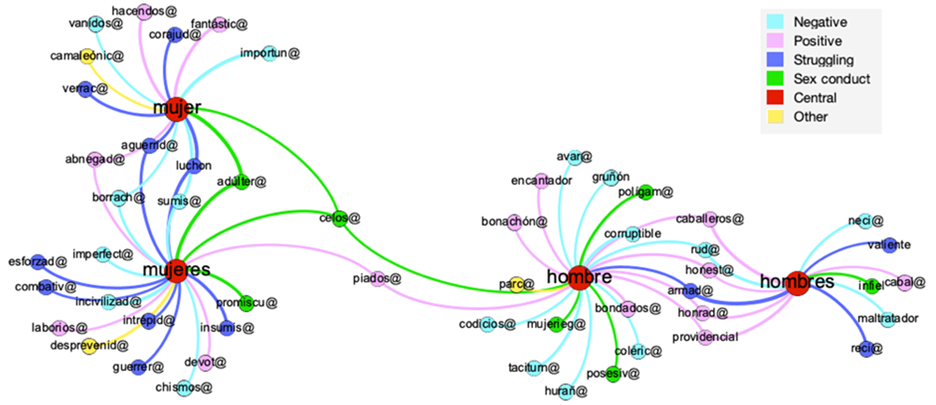

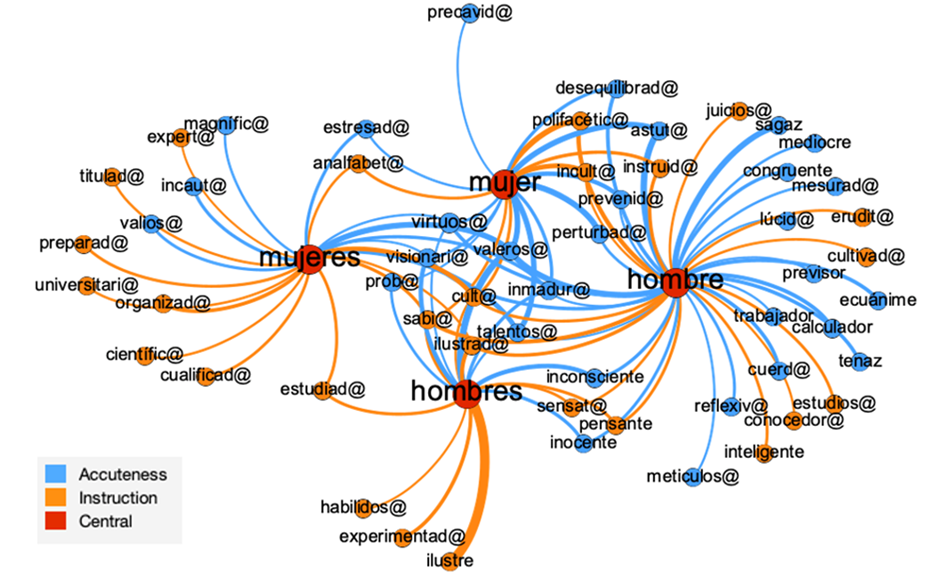

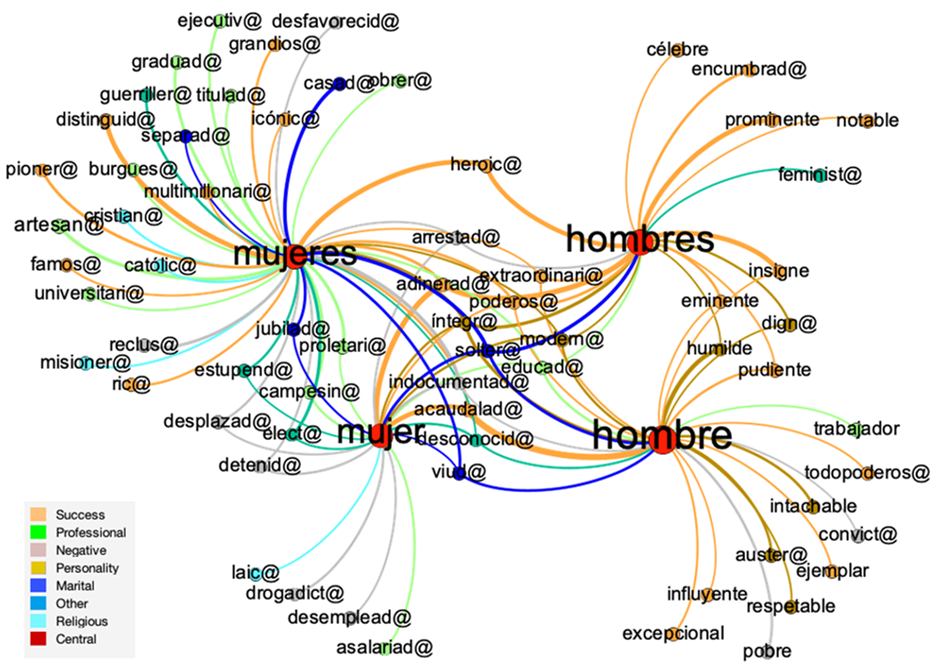

In the following graphs, the nodes represent lemmas and the edges represent word co-occurrences, that is, collocations. Edges are colored according to the collocate category; their thickness represents their MI statistic. Figure 5 shows results obtained for the Behavior category. Here, due to the number of adjectives extracted, adjective types with an MI above 6.5 are shown for this category. k

In the above constellation, a semantic field associated with struggling is colored in dark blue, and in it, adjectives such as combativa ‘combative’, esforzada ‘hard-working’, guerrera ‘warrior’, intrépida ‘fearless’, insumisa ‘unsubmissive’, aguerrida ‘tough’, luchona ‘hard-working’, and verraca ‘clever’ only appeared with woman. Out of these adjectives, unsubmisive has one of the highest MI scores; this means that unsubmissive appeared nearly exclusively with women, which in turn points out to the fact that it is much more common for women to be described as unsubmissive than men.

The concept of ‘markedness’ addresses what the terms marked and unmarked mean. Marked refers to the way the meaning of a word is altered by adding a linguistic particle (in this case, an adjective) while an unmarked term carries the meaning that does not require specification. The Struggling semantic field’s adjectives all tend to appear with the lemma woman. This implies that women can be fearless, unsubmissive, and combative should not be taken for granted. On the other hand, the fact that these adjectives did not collocate with man could also imply that fearlessness, un-submissiveness, and combativeness are generally considered default characteristics of men.

Adjectives with green nodes such as promiscua ‘promiscuous’ and adúltera ‘adulterous’ collocate only with woman and women and the adjectives polígamo ‘polygamous’, mujeriego ‘womanizer’, and posesivo ‘possessive’ collocate with man while infiel ‘unfaithful’ collocates with men. Such adjectives are usually related to sexual conduct. Out of these adjectives, adúltera and adúlteras had an MI score of 10 and 9 respectively; in all the data there was only one adjective besides adulterous, with an MI score above 10. What this finding indicates is that women are more likely to be associated with adultery and described as such. A similar adjective, infiel ‘unfaithful’, collocates with men but not with woman or women. Adulterous and unfaithful are at times used interchangeably without considering their denotative meaning in legal contexts. Taking into account that from a legal standpoint adultery is described as having a sexual relationship with somebody other than one’s spouse, adultery is generally accepted as a legal cause to seek divorce. On the other hand, unfaithfulness is considered a vague and subjective term in legal contexts; somebody may be accused of being unfaithful for flirting or maintaining an emotional relationship with somebody; in other words, being accused of being unfaithful does not necessarily imply having a sexual relationship. Based on the above, it could be argued that women are more harshly represented in the NOW corpus. The choice of words people use to represent women in this corpus goes beyond a mere representation; such words seem to criminalize women’s behavior but not men’s.

Some adjectives shown in the constellation network were hard to place within a semantic field; yet it can be noted that certain adjectives only collocate with woman and some only with man. For example, the adjectives devotas ‘devoted’ and abnegada(s) ‘self-sacrificing’ only collocate with woman. Such adjectives refer to somebody who dedicates her/his life to the well-being of others or somebody who surrenders her/his life expectations to serve or please somebody else. In any case, the fact that these adjectives only collocate with woman could suggest that there are social customs or expectations that only relate to women.

A group of negative adjectives seemingly indicating a lack of self-restraint were also identified. They are maltratador(es) ‘abusive’, necio ‘foolish’, cólericos ‘choleric’, codiciosos ‘greedy’, and avaros ‘stingy’, collocating only with man, and adjectives such as corajuda ‘short-tempered’ and chismosas ‘gossipy’, collocating with woman. The contrast between maltratadores and chismosas might be interpreted as men physically, emotionally, and/or psychologically mistreating people whereas women merely gossip about people but will not reach the point of physically mistreating somebody. As mentioned earlier in this document, this study focuses on a lexical analysis, but there is no doubt that the information can be exploited from the perspective of other areas such as women’s studies or sociolinguistics. This research reveals connections between gender violence and the linguistic representation of women and men. Considering the legal definitions of the adjectives ‘adulterous’ and ‘unfaithful’ and that the former only collocates with women and the latter with men, it may mean that this somehow represents verbal violence towards women. The same can be said of adjectives ‘self-sacrificing’ and ‘devoted’, which only collocate with ‘women’; in this case, it could be argued that society may have some expectations from women only, and this could be a form of verbal violence.

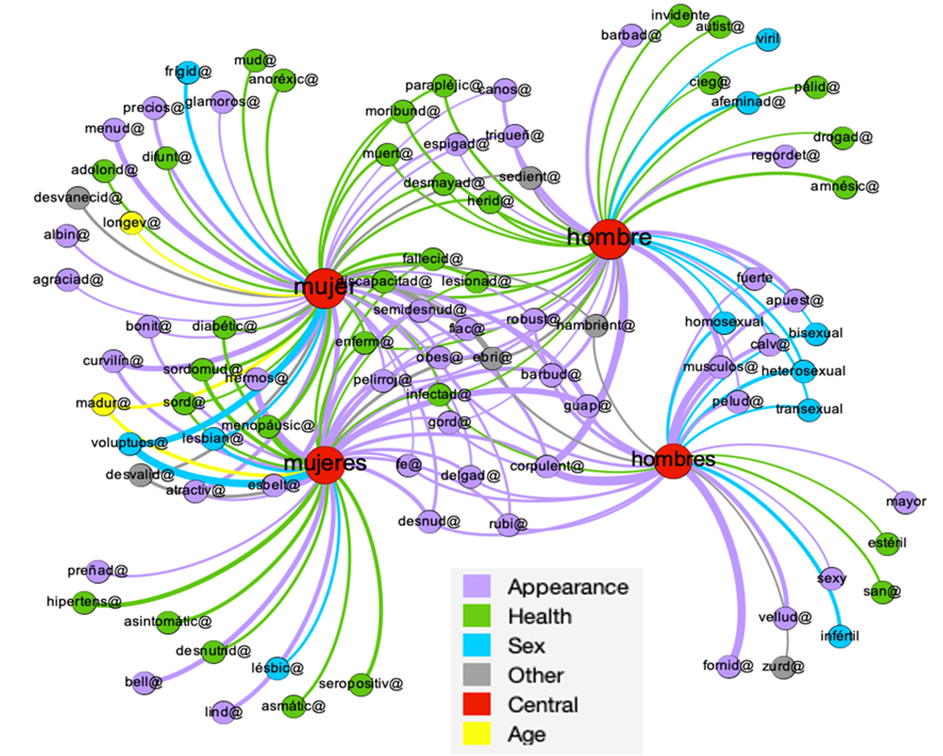

The next constellation network reflects adjective types identified with an MI above 4 from the Body category. As it can be observed, some adjectives collocate only with one of the man or woman lemmas, and in some cases, some adjectives appeared only in the singular or plural form; in many other cases, some adjectives appeared with both lemmas (center of the image).

For this category, collocations were also grouped in semantic fields when possible. Very few adjectives were identified in the semantic field labeled as age; the adjectives longeva ‘long-lived’ and madura(s) ‘mature’ collocate with woman and mayores ‘senior’ with man. No adjective with a high MI score related to youth was found to collocate with either man or woman. This was an unexpected finding because previous similar research has found plenty of collocations regarding age and aging with both lemmas. If adjectives with a lower MI score had been included in this analysis, more adjectives related to age and aging would have appeared.

Several adjectives in this constellation were also placed in a semantic field category labeled Health. The adjectives ad Florida ‘sore’, anoréxica ‘anorexic’, and muda ‘mute’ collocate with woman and hipertensa ‘hypertense’, asmática ‘asthmatic’, desnutrida ‘malnourished’, while asintomática ‘asymptomatic’ collocate with women; diabética ‘diabetic’, menopáusica ‘menopausal’, sordomuda ‘deaf-mute’, sorda ‘deaf’, and desvalida ‘helpless’ collocate with both singular and plural forms. As for the plural men, only infértil ‘infertile’ and estéril ‘sterile’ collocate with it, and pálido ‘pale’, autista ‘autistic’, ciego ‘blind’, and invidente ‘blind’ collocate with man. Connotations of some adjectives that collocate with woman imply more serious health issues. Sterile and infertile have subtle differences; both men and women can be sterile and infertile but these adjectives only collocate with man. Twice as many adjectives that relate to health issues collocate with woman than with man. The following adjectives collocate with both lemmas: parapléjico(a) ‘paraplegic’, herida(o) ‘wounded’, desmayado(a) ‘unconscious’, moribunda(o) ‘dying’, fallecido(a) ‘deceased’, obesa(o) ‘obese’, lesionado(a) ‘injured’, enferma(o) 'sick’, discapacitado(a) ‘disabled’, and infectada(o) ‘infected’.

Another group of adjectives in this constellation was placed within a semantic field labeled Physical appearance. For example, the adjectives agraciada ‘gifted’, preciosa ‘beautiful’ and glamorosa ‘glamorous’ collocate with woman; bellas and lindas ‘pretty’ with women and hermosa(s) and bonita(s) ‘beautiful’ with both. Regarding man in its singular form, viril ‘manly’ and barbado ‘bearded’ collocate with it, the adjectives velludos ‘hairy’ and sexys ‘sexy’ collocate with men, and apuesto(s) ‘handsome’ and peludo(s) ‘hairy’ collocate with both forms. The only adjective that collocates with both singular and plural lemmas is guapa(o) ‘good-looking’. Most adjectives have a positive polarity since they refer to men’s and women’s good looks. Adjectives referring to individual looks sometimes overlap with adjectives related to body type; for example, while anorexic collocates with woman; and esbelta(s) ‘slender’, voluptuosa(s) ‘voluptuous’, atractiva(s) ‘attractive’, and curvilínea(s) ’curvy’ collocate with both woman and women. Regordete ‘chubby’ only collocates with man; fornidos ‘well-built’ with men; and musculoso(s) ‘muscular’ and fuerte(s) ‘strong’ collocate with both. Delgada(o) ’thin’, gordo(a) ‘fat’, obesa(o) ‘obese’, corpulento(a) ‘stout’, robusta(o) ‘sturdy’, flaco(a) ‘skinny’, and espigada(o) ‘lank’ collocate with both lemmas in the singular and plural.

The last sub-group identified within the Body category is labeled Sexuality; the only adjective that collocates with the node woman was frígida ‘frigid’, whereas lésbicas ‘lesbic’ collocates with women, and lesbiana(s) ‘lesbian’ collocates with both. As for man, afeminado ‘effeminate’ collocates with it, bisexuales ‘bisexuals’ appears with men, and heterosexual(es) ‘heterosexual’, homosexual(es) ‘homosexual’, and transexual(es) ‘transsexual’ patterns with both forms.

In the Mind category 66 adjectives with an MI above 4 collocate with the lemma man and 28 with the lemma woman.

The first semantic field identified in this constellation network was labeled as Instruction (orange nodes), and this was more conspicuous when observing adjectives that exclusively collocate with women and men. Adjectives cualificada ‘qualified’, titulada ‘graduated’, organizada ‘organized’, preparada ‘skilled’, universitaria ‘university student’, científica ‘scientist’, experta ‘expert’, estudiada ‘educated’ collocate with women, and sensato ‘judicious’, pensante ‘thoughtful’, habilidoso ‘skillful’, experimentado ‘experienced’, and ilustre ‘illustrious’ with men. A close reading of the contrast between these adjectives reveals another bias: the ones that collocate with men seem to suggest some kind of natural ability (they are labeled judicious, skillful, illustrious, or experienced); with women those abilities are absent and only their level of education is pointed out (of all the adjectives mentioned above, only estudiado/a ‘educated’ collocates with both lemmas).

The Mental Acuteness semantic field (blue nodes) groups adjectives regarding people’s abilities to focus, recall, and reason. This semantic field was more evident when analyzing adjectives that collocate with the singular form of both lemmas. There are many more adjective types with man than with woman. The adjective precavida ‘cautious’ collocate with woman and the following adjectives patterned with man: tenaz ‘tenacious’, cuerdo ‘sane’, congruente ‘congruent’, juicioso ‘judicious’, previsor ‘far-sighted’, meticuloso ‘meticulous’, sagaz ‘sagacious’, ecuánime ‘unbiased’, inteligente ‘intelligent’, reflexivo ‘thoughtful’, lúcido ‘lucid’, and mesurado ‘prudent’; the adjectives astuta(o) ’shrewd’ and prevenida(o) ‘far-sighted’ collocate with both lemmas even though they pattern strongly with woman. Again, men are more salient in terms of mental sharpness and wisdom.

The last constellation network presented and discussed relates to the Social category that yielded more adjective types collocating with woman than with man; however, due to a large number of adjectives, only those with an MI above 4 are shown in the constellation network. Several of the adjectives in such constellations (see Figure 4) were grouped in a semantic field labeled Social Prominence. Adjectives desempleada ‘unemployed’, drogadicta ‘drug addict’, asalariada ‘salaried’ (as in salaried employee), laica ‘lay’ and estupenda ‘wonderful’ (red nodes) only collocate with woman in its singular form whereas ejemplar ‘exemplary’, respetable ‘respectable’, excepcional ‘unique’, influyente ‘influential’, intachable ‘flawless’, todopoderoso ‘all-mighty’, trabajador ‘hard-working’, convicto ‘convict’, austero ‘austere’, and pobre ‘poor’ (green nodes) collocate with man. It was observed that while man is more strongly represented as being full of prominent positive qualities, only the adjective wonderful is associated woman.

Concerning the same semantic field and the adjectives that collocate with both lemmas but in their plural form, it was found that célebre ‘famous’, encumbrado ‘exalted’, prominente ‘prominent’, and notable ‘remarkable’ collocate with men whereas distinguidas ‘distinguished’, pioneras ‘pioneers’, multimillonarias ‘multi-millionaire’, famosas ‘famous’, ejecutivas ‘executive’, ricas ‘wealthy’, and icónicas ‘iconic’ collocate with women. What this shows is that, at least in the NOW corpus, women, in plural, are more likely to be represented as being prominent but it is not the case when referring to a particular woman. Despite the fact that the scope of this research attempts to indicate outstanding features related to gender study analysis or discourse analysis approaches, this finding seems to suggest that women appear to be subjected to a deindividuation process. The data suggest that women are represented as a community rather than as individuals. Such a deindividuation process seems to inadvertently marginalize women’s identities as evidenced in the corpus.

Another interesting finding in this constellation network is that the adjectives separada ‘separated’, casada ‘married’, cristiana ‘Christian’, and católica ‘Catholic’ collocate exclusively with women and viuda(o) ‘widow/widower’ and soltera(o) ‘single’ collocate with both lemmas. Previous research has shown that women are more strongly associated with adjectives associated with marital status. Of all these adjectives, solteras ‘single’ has the highest MI score which means that women tend to be more strongly associated with marital status than men; there was no adjective related to marital status or religious affiliation that collocates exclusively with the lemma man in either its plural or singular form.

8. CONCLUSION

As has been previously mentioned, the aim of this study is twofold. First, to use CL methods and tools to reveal social and cultural information with respect to gender representation in Spanish, and second, to propose the combined use of CL methods and tools with network graphs to inform DH.

Regarding the first objective of this research, although much of the criticism regarding the use of CL in sociolinguistics relates to the idea that CL is too focused on quantifying, which may result in over-simplification, stereotyping, or prejudice reinforcement, it is clear that CL can contribute to existing research paradigms. In the previous four constellation networks, women and men are linguistically represented through an appraisal of adjectival collocations. Women tend to be associated, at least in the NOW corpus, with health issues and with facing inequalities; taking into account social, political, and economic inequalities between men and women, it seems that such inequalities are represented in language since women are described as dealing with failing health and power structure disadvantages. In this corpus women also pattern strongly with marital status and religious affiliations whereas men strongly collocate with fertility and sexuality issues. Several adjectives only appeared with women as in the case of adulterous; and, in the case of men, unfaithful, as mentioned above. Furthermore, men are generally described in terms of mental sharpness and social prominence. Another interesting finding is that it seems that both men and women experience a process of deindividuation that appears to prioritize the identity of a group over individual identities, which causes the stereotyping of males and females seen as communities, with an apparent disregard for individual identities. Furthermore, the lemma man as a stand-alone is considered the norm whereas the lemma woman is marked and requires more adjectives. Stereotypical language in the press should not come as a surprise since gender is a social construct rooted in discourse.

As most research of this kind, this study presents some limitations concerning data, analysis, and interpretation that may be reduced if the following steps are addressed. In addition to collocational analysis, data concordance analysis could be conducted, and by doing so collocate behavior in context may be identified. By analyzing excerpts (concordances), in addition to graph networks, new discourses can be revealed, leading to more robust analyses. Furthermore, the NOW corpus can be divided according to year and country, and this can reveal variations in the collocations obtained and their analysis can be enriched. With regards to data analysis, this work followed a ‘representation’ rather than a ‘usage’ paradigm and there are practical reasons for this; however, in research of this kind, it might be enriching to include the gender of the authors of corpus samples as a new variable from which to establish how dissimilarly male journalists write as opposed to female journalists. Finally, this work lies in the intersection among corpus linguistics, DH, discourse analysis, and gender studies; by engaging in multidisciplinary work, researchers can facilitate and expand the interpretation of linguistic data through their extensive knowledge of literature, analytic approaches, and awareness of the limitations that research studies face from the perspective of their field of studies.

This study demonstrates the value of using corpus methods to examine the use of gender-marked language that tends to perpetuate differences. Any conclusions about how women and men are linguistically represented must be made with the proviso that they are not representative of all Spanish and Latin American press, let alone speakers of Spanish. A collocational analysis such as the one undertaken in this study might be useful for further qualitative discussion. Concerning the second goal of this study, which is to promote CL and its methods and tools in DH, by relying on CL methods and tools and network representations of data, digital humanists can search across large bodies of texts and analyze data in ways that were not previously possible. CL tools and methods enable finding patterns in large amounts of data that would otherwise be very difficult to identify. A collocational analysis via a specific corpus may expand research findings not only in linguistics but also in other fields. The aim is to show that the use of graphs to analyze collocations has allowed for a broader view of the relationship between collocates and lemmas; with this in mind, the use of graphs can be useful to analyze data in different studies within DH. By employing diverse approaches to data analysis, hidden meanings may be made evident, and this could eventually lead to posit new research questions and hypotheses.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Alochis, I. (2016). La representación de la violencia sexual contra las mujeres y las niñas en el léxico y en la construcción discursiva de las noticas en un estudio de caso en la prensa gráfica de Córdoba. Coloquio interdisciplinario internacional “Educación sexualidades y relaciones de género”. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. https://rdu.unc.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/11086/20777/EJE_2.pdf

Anthony, L. (2005). AntConc: A Learner and Classroom Friendly, Multi-Platform Corpus Analysis Toolkit. Proc. IWLeL 2004: An Interactive Workshop on Language e-Learning, 7-13. Waseda University.

Anthony, L. (2022). TagAnt (2.0.4) [All OS]. Waseda University. http://www.laurenceanthony.net/

Baker, P. (2010a). Representations of Islam in British broadsheet and tabloid newspapers 1999-2005. Journal of Language and Politics, 9(2), 310-338.

Baker, P. (2010b). Will Ms ever be as frequent as Mr? A corpus-based comparison of gendered terms across four diachronic corpora of British English. Gender and Language, 4(1), 125-149. https://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v4i1.125

Baker, P. (2012). Corpora and Gender Studies. In K. Hyland, C. Meng Huat, & M. Handford (Eds.), Corpus Applications in Applied Linguistics (pp. 100-116). Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472541611.ch-007

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., & McEnery, T. (2013). Discourse analysis and media attitudes: The representation of Islam in the British Press. Cambridge University Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The Dialogic Imagination: Four essays. University of Texas Press.

Barlow, M. (1999). MonoConc 1.5 and ParaConc. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 4(1), 173-184. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.4.1.09bar

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. Proc. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, 361-362.

Bednarek, M. (2016). Voices and Values in the News: News Media Talk, News Values and ttribution. Discourse, Context and Media, 11, 27-37.

Biber, D. (2011). Corpus Linguistics and the Study of Literature: Back to the Future? Scientific Study of Literature, 1(1), 15-23.

Brezina, V. (2018). Statistics in Corpus Linguistics: A Practical Guide. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316410899

Caldas-Coulthard, Carmen. R., & Moon, R. (2010). ‘Curvy, hunky, kinky’: Using Corpora as Tools for Critical Analysis. Discourse & Society, 21(2), 99-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926509353843

Castillo, María N. (2019). ¿Qué se dice de la mujer y el hombre en el español de Chile?: studio exploratorio de las combinaciones frecuentes de los vocablos mujer y hombre en un corpus de referencia estratificado. Boletín de filología, 54(1), 95-117.

Coates, J. (2015). Women, Men and Language: A Sociolinguistic Account of Gender Differences in Language. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315645612

General Law on Women's Access to a Life Free from Violence (2007). https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGAMVLV.pdf

Davis, M. (2020). Corpus of News on the Web (NOW). Available online at https://www.english-corpora.org/now/

Dixon, R. M. W. (2010). Where have all the adjectives gone? And other essays in semantics and syntax. De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110822939

Duby, G., & Perrot, M. (Eds.). (1992). A History of Women in the West (Vol. 1). Harvard University Press.

Evert, S. (2008). Corpora and Collocations. In A. Lüdeling & M. Kytö (Eds.), Corpus Linguistics: An International Handbook (pp. 1212-1248). W. de Gruyter.

Fellbaum, C. (1998). WordNet: An Electronic Lexical Database Cambridge. MIT press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/7287.001.0001

Flowerdew, J., & Richardson, J. E. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Analysis. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739342

Fraisse, G., & Perrot, M. (Eds.). (1993). Historia de las mujeres en Occidente. Tomo 4. El siglo XIX. Taurus.

Gregory, I., Donaldson, C., Murrieta-Flores, P., & Rayson, P. (2015). Geoparsing, GIS and Textual Analysis: Current Developments in Spatial Humanities Research. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 9(1), 1-14.

Hardie, A. (2020). CQPweb [Computer Software]. Available from http://cwb.sourceforge.net/index.php

Kendall, S, & Tannen, D. (2015) Discourse and Gender. In D. Schifrin, D. Tannen, & H. Hamilton (Eds.), The Handbook of Discourse Analysis (pp. 639-660). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118584194.ch30

Kilgarriff, A. (2020). Sketch Engine [Computer Software]. https://www.sketchengine.eu/

Klapisch-Zuber, C. (Ed.). (1992). Historia de las mujeres en Occidente. Tomo 2. La Edad Media. Taurus.

Laviosa, S. (2002). Corpus-based translation studies: Theory, findings, applications. Rodopi.

Litosseliti, L. (2014). Gender and Language Theory and Practice. Routledge.

Manning, C. D., & Schütze, H. (1999). Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing. MIT Press.

Martin, J. R., & White, P. R. R. (2005). The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230511910

Mautner, G. (2007). Mining Large Corpora for Social Information: The Case of Elderly. Language in Society, 36(1), 51-72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404507070030

McEnery, A., & Baker, P. (2015). Corpora and Discourse Studies: Integrating Discourse and Corpora. Springer.

McEnery, T., & Baker, H. (2016). Corpus Linguistics and 17th-century Prostitution: Computational linguistics and history. Bloomsbury.

McEnery, T., & Hardie, A. (2011). Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Montgomery, M. (2007). The Discourse of Broadcast News: A Linguistic Approach. Routledge.

Moon, R. (2014). From Gorgeous to Grumpy: Adjectives, Age, and Gender. Gender and Language, 8(1), 5-41. https://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v8i1.5

National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics. (2016a). Mortality Statistics. https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/mortalidad/

National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics. (2016b). National Survey on the Dynamics of Relationships in Households. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/endireh/2016/

Nolte, M. I., Ancarno, C., & Jones, R. (2018). Inter-religious Relations in Yorubaland, Nigeria: Corpus Methods and Anthropological Survey Data. Corpora 13(1), 27-64.

Padró, L., & Stanilovsky, E. (2012). FreeLing 3.0: Towards Wider Multilinguality. Proceedings of the Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC 2012). http://nlp.lsi.upc.edu/freeling/node/1

Pearce, M. (2008). Investigating the Collocational Behavior of Man and Woman in the BNC Using Sketch Engine. Corpora, 3(1), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.3366/E174950320800004X

Romaine, S. (2000). Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Oxford University Press.

Schmitt Pantel, P., & Pastor, R. (Eds.). (1991). Historia de las mujeres en Occidente. Tomo 1. La Antigüedad (Vol. 1). Taurus.

Scott, M. (1996). Wordsmith Tools. Oxford University Press.

Sigley, R., & Holmes, J. (2002). Looking at Girls in Corpora of English. Journal of English Linguistics, 30(2), 138-157. https://doi.org/10.1177/007242030002004

Thébaud, F. (Ed.). (1993). Historia de las mujeres en Occidente. Tomo 5. El siglo XX. Taurus.

Tribble, C. (2015). Teaching and language corpora: Perspectives from a personal journey. In A. Boulton & A. Leńko-Szymańska (Eds.), Multiple affordances of language corpora for data driven learning (pp. 57- 64). John Benjamin Publishing Company.

Tsvetkov, Y., Schneider, N., Hovy, D., Bhatia, A., Faruqui, M., & Dyer, C. (2014). ‘Augmenting English Adjective Senses with Supersenses’. Proc. the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’14), European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

Van Leeuwen, T. (2013). The Representation of Social Actors. In C. R. Caldas-Coulthard, & M. Coulthard (Eds.), Texts and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis (pp. 41-79). Routledge.

Weatherall, A. (2005). Gender, Language and Discourse. Routledge.

Zemon Davis, N., & Farge, A. (Eds.). (1992). Historia de las mujeres en Occidente. Tomo 3. Del Renacimiento a la Edad Moderna. Taurus.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3900-2356

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3900-2356