1. INTRODUCTION1

The study of cultural discourse2 in works of electronic literature3 can give us a panorama of the connections and variations that exist between the digital production of different geographic regions. Digital humanities methods are a way to explore such cultural elements particularly when the creation of collections, anthologies and databases is at the core of multiple international electronic literature research projects (The Consortium on Electronic Literature (CELL), 2015; The Electronic Literature Collections Vols. 1-3., 2006; The ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Base, 2010). Even though recent studies have noted the advantages of applied methods for distant reading analysis (Moretti, 2005) and macroanalysis (Jockers, 2013) in electronic literature research (Pawlicka, 2016; J. W. Rettberg, 2014; S. Rettberg, 2014; Seiça, 2016), such approaches are still hardly used in the field.

Evidence suggests that the application of these methods to explore electronic literature (hereafter e-lit) materials can be very useful to extract new information (trends, patterns, similarities) about the e-lit works. In Latin American e-lit research, there are currently no studies that methodologically apply distant reading techniques to examine any features of the works. Therefore, the aim of the present research is to address this lack by applying distant reading methodologies such as graphs to analyze networks of cultural discourses in a corpus of 30 Latin American e-lit works published from 1995 to 2020.

To develop my research, firstly, I apply close reading to study the manifestations of cultural discourse in the e-lit works. For that, I use theories from Discourse Analysis (Carbaugh, 2007; Gee, 2014) and Latin American Cultural Studies (Taylor & Pitman, 2013), as well as digital tools such as eMargin (2015)4, a collaborative textual annotation tool, to qualify the appearance of the discourses5. Secondly, I apply distant reading (graphs) to examine the relations between the e-lit works and the cultural discourses, and subsequently, the co-occurrence between the discourses themselves. To plot the graphs, I use Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009)6, an open-source software for the exploration and analysis of network visualizations.

This methodological approach was employed to examine the following research questions: 1. How are cultural discourses related in a corpus of 30 Latin American e-lit works? 2. What are the primary, secondary, and tertiary discourses in the works? 3. What is the degree of multi-discourse? 4. How does discourse co-occurrence reveal different patterns? And lastly, 5. How can we build bridges between traditional methods of analysis and digital humanities tools (e.g., data visualization techniques) to study not only networks of cultural discourses but also other features of Latin American e-lit (e.g., genres, themes, technological apparatus)?

2. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY

As mentioned above, very little has been found in the literature review on the question of applied methods for distant reading analysis (Moretti, 2005) and macroanalysis (Jockers, 2013) when it comes to exploring e-lit materials. Undoubtedly, the studies of J. W. Rettberg, (2014), S. Rettberg, (2014), Á. Seiça, (2016) and U. Pawlicka, (2016) stand as ground-breaking examples of the application of certain distant reading methods, such as graphs (Bastian et al., 2009) and tag clouds to examine different aspects of e-lit. These studies have shown that not only can distant reading approaches broaden existing e-lit methodologies to analyze citation rates and genre evolution in large databases such as ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Database7 and the Electronic Literature Collections Vols. 1-38, but they can also help to reevaluate and thus reshape current research methodologies of the field, pointing towards an interdisciplinarity between Electronic Literature and Digital Humanities research methods.

Moreover, the study of cultural discourse in works of electronic literature has been approached from different disciplines in recent years (e.g., Sociological Studies, Cultural Studies, Literary Studies). In the field of Latin American Cultural Studies, pioneers Claire Taylor and Thea Pitman (2013) underline that “Latin American(ist) discourses that pre-existed the Internet and have already long histories in Latin America, adapt, transmute, or perpetuate themselves in online cultural productions giving rise to new artistic and literary forms” (p. 1). Based on different case studies, the scholars propose the following classification of discourses and conceptualizations of Latin American-ness in online cultural production: “a) the mapping of the entity called ‘Latin America’; b) the lettered city; c) the magical real; d) the discourse of racial mixing or mestizaje; e) the dichotomy of civilization versus barbarism; f) the concept and practice of revolution” (p. 23).

In a recent paper, Meza (2019) developed a close reading methodology based on Taylor and Pitman’s discourse classification to analyze the role of digital rhetorical practices in the construction of cultural discourses in Latin American e-lit works. The analyses showed that certain discourses were more frequent than others, and consequently co-occurred in more than one e-lit work creating interesting relations. However, the number of works in the study was too small to draw any conclusions at a regional production level. Therefore, I argue that one way to investigate this further is to analyze the relations between the cultural discourses and the e-lit works in a larger corpus by applying distant reading methods such as graphs. For distant reading may reveal unexpected connections and hidden patterns that close reading may not find. Not to mention that the study of cultural discourse variations in the e-lit works has significant implications for the understanding of the styles of communication of the artists, the practices of communication of the works, and the connections and variations that may exist within the digital literary production in Latin America.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Data Collection

Currently there are not available open-access databases specific to the production of Latin American e-lit. Even though the Antología Lit(e)Lat Vol. 1 (Flores et al., 2020)9 has been launched past December, the database is not yet accessible. Thus, due to the difficulties of gathering information from a single database, different sources for the selection of the corpus were examined: the three Electronic Literature Organization Collections, ELC1 (Hayles et al., 2006)10, ELC2 (Borràs et al., 2011)11, ELC3 (Boluk et al., 2016)12; the ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Base (2010)13, specifically the Brasilian and Spanish collections (Gattass, 2012; Zalbidea, 2014); as well as other international collections and databases, such as the Spanish project CIBERIA (Goicoechea & Sánchez, 2014)14, the literature section of the Cultura Digital Chile project (Gainza, 2016)15, the Mexico City- based Center for Digital Culture’s E-literature Collection (Antología de poesía electrónica, 2018)16, the Atlas de Literatura Digital Brasileira (Rocha, 2019)17 and the Argentinian, Paraguayan and Uruguayan, Itaú Anthology of Digital Stories (Antologías de Cuento Digital Itaú, 2011)18.

All the e-lit works used in the analyses and network visualizations are documented and archived in these databases and collections. The selection of the e-lit works met the following geographical, stylistic, linguistic, and literary criteria: a) the e-lit works had to be created by Latin American born authors; b) the authors had to be individual creators or collectives; c) the e-lit works had to be written in Spanish or Portuguese19; d) the e-lit works had to belong to different e-lit genres and generations; e) the e-lit works had to be published in a 25-year period (1995-2020); f) the e-lit works had to be archived in e-lit databases, collections or anthologies reviewed by a scientific committee.

The table below (Table 1) illustrates the 30 e-lit works -published from 1995 to 2020- that were used to analyze networks of cultural discourses.

|

ID |

Work |

Year |

Author |

Country |

Genre |

|

1 |

Anipoemas20 [Anipoems] |

1997 |

Ana María Uribe |

Argentina |

Animated poetry |

|

2 |

Mr. President21 [Mr. President] |

1999 |

Angie Bonino |

Peru |

Video-poetry |

|

3 |

Pentagonal22 [Pentagonal] |

2001 |

Carlos Labbé |

Chile |

Hypertextual narrative |

|

4 |

PanPaz imagine23 [BreadPeace imagine] |

2001 |

Clemente Padín & Alexandre Venera |

Uruguay- Brasil |

Interactive poetry |

|

5 |

Amor torbellino24 [Whirlpool love] |

2001 |

Isabel Aranda |

Chile |

Animated poetry |

|

6 |

Oratorio25 [Oratory] |

2003 |

André Vallias |

Brasil |

Multimedia narra- tive |

|

7 |

Tejido de memoria26 [Weaving memory] |

2003 |

Marina Zerbarini |

Argentina |

Multimedia narrative |

|

8 |

Bacterias argentinas27 [Argentinian Bacteria] |

2004 |

Santiago Ortiz |

Colombia |

Generative narrative |

|

9 |

El alebrije28 [The Alebrije] |

2004 |

Carmen Gil & Camilo Giraldo |

Colombia |

Multimedia narra- tive |

|

10 |

Hembros29 [Fe/males] |

2004 |

Eugenia Prado |

Chile |

Transmedia/ Installation novel |

|

11 |

Olhar axolotes30 [Viewing axolotls] |

2004 |

Regina Celia Pinto |

Brasil |

Interactive narrative |

|

12 |

Setenta y uno31 [Seventy-one] |

2004 |

Carlos Cociña |

Chile |

Hypertextual poetry |

|

13 |

Grita32 [Shout] |

2004 |

José Aburto |

Peru |

Generative poet- ry |

|

14 |

Labo/Laboratorio de ciberpoesía33 [Labo/Laboratory of cyberpoetry] |

2009 |

Karen Villeda |

Mexico |

Interactive poetry |

|

15 |

Poema terremoto34 [Earthquake poem] |

2010 |

Gregorio Fontén |

Chile |

Interactive poetry |

|

16 |

Augusto35 [August] |

2011 |

Adriana Calcahotto |

Brasil |

Interactive poetry |

|

17 |

Liberdade36 [Liberdade] |

2013 |

Chico Marihno et al. |

Brasil |

Multimedia narrative |

|

18 |

Tatuaje37 [Tatoo] |

2014 |

Rodolfo JM et al. |

Mexico |

Hypertextual narrative |

|

19 |

El 2738 [The 27] |

2014 |

Eugenio Tisselli |

Mexico |

Generative narra- tive |

|

20 |

Umbrales39 [Thresholds] |

2014 |

Yolanda de la Torre, et al. |

Mexico |

Multimedia narrative |

|

21 |

Hotel Minotauro40 [Minotaur Hotel] |

2015 |

Doménico Chiappe |

Peru- Venezuela |

Multimedia narrative |

|

22 |

Retratos vivos de mamá41 [Living portraits of my mother] |

2015 |

Carolina López |

Colombia |

Multimedia nar- rative |

|

23 |

Paisajes42 [Landscapes] |

2015 |

Laura Benech |

Argentina |

Multimedia installation |

|

24 |

Memorias y caminos43 [Memories and pathways] |

2016 |

Jaime Alejandro Rodríguez |

Colombia |

Multimedia narrative |

|

25 |

Gorila esquizo44 [Gorila esquizo] |

2017 |

Milton Läufer |

Argentina |

Twitter bot |

|

26 |

Mexica45 [Mexica] |

2017 |

Rafael Pérez y Pérez |

Mexico |

Generative narrative |

|

27 |

Mandala46 [Mandala] |

2017 |

Alejandra Jaramillo |

Colombia |

Multimedia narrative |

|

28 |

Cae47 [Fall] |

2018 |

Loren Pose |

Uruguay |

Hypertextual narrative |

|

29 |

E-Imigrações48 [E-migraciones] |

2019 |

Alckmar dos Santos, et al. |

Brasil |

Multimedia nar- rative |

|

30 |

Coronário49 [Coronary] |

2020 |

Giselle Beiguelman |

Brasil |

Hypertextual essay |

3.2. Data Analysis

The selected e-lit works were published from 1995 to 2020 and belong to seven different countries: Argentina (4 works), Brasil (6 works), Chile (5 works), Colombia (5 works), Mexico (5 works), Peru (3 works) and Uruguay (2 works). To develop my research, firstly, a close reading methodology was applied for the analysis of cultural discourses (Meza, 2019) to each group. The methodology consisted of different steps: 1) the linguistic transcription of the different semiotic forms that composed each e-lit work (linguistic text, images, audios, videos) by using audio recording, screen shots or filmed navigation videos; 2) the analysis of the different cultural discourses found in the transcribed linguistic texts: a) Latin American entity; b) lettered city; c) the magical real; d) racial mixing or mestizaje; e) civilization vs. barbarism; f) revolution (Taylor & Pitman, 2013, p. 23); and 3) the analysis of the stylistic devices used to express the cultural discourses such as figures of animation and manipulation (Bouchardon, 2014; Saemmer, 2015), and digital rhetorical practices (Brooke, 2009; Eyman, 2015).

As part of the innovative aspect of this paper and considering that the production of e-lit works in Latin America responds to economic, political, and socio-cultural factors50, four new discourse categories were added to the initial proposition made by Taylor and Pitman (2013). These new categories are the following: g) gender, h) scientific, i) nature51 and j) political. This proposition was based on the appearance, the frequency, and the co-occurrence that these new discourses showed in relation to the original six discourses in the close reading analyses52. I then used eMargin (2015)53, a collaborative textual annotation tool, to qualify the appearance of the ten cultural discourses in the e-lit works. All the gathered information from the close reading was stored into different datasets using a spreadsheet tool before the visualization strategy.

3.3. Visualization Strategy

There are many challenges in the process of creating a visualization and certainly a lot of ways to measure its features. In a recent paper, S. Jänicke, G. Franzini, M. F. Cheema and G. Scheuermann (2015) argued that visualization techniques have gained significant importance in the humanities when it comes to analyzing textual data. In their study, the authors present an excellent overview of the last ten years of research on visualizations that undoubtedly have supported close and distant reading methodologies. The paper skillfully shows the utility of a great number of close reading (color, font size, glyphs, connections) and distant reading (structure, heat maps, tag clouds, maps, timelines, graphs, miscellaneous) visualization techniques that are currently being used by scholars working in the digital humanities (Jänicke et al., 2015).

To develop this paper, Gephi (version 0.9.2) (Bastian et al., 2009), a tool for the exploration and analysis of network visualizations, was used to create the visualization of the relation of cultural discourses in 30 Latin American e-lit works published from 1995 to 2020. For this software has successfully been applied to visualize the relationships between texts in a corpus in different digital humanities projects (Bonato et al., 2016; Eder, 2017; Gandolfi, 2018; Labatut & Bost, 2019).

Network graphs in Gephi are constructed by nodes (points in a network) and edges (connections between nodes) and can be directed (the direction of the edges has an origin and a destination) or undirected (the edges have mutual connections) depending on the purpose of the visualization. That said, the first step in any visualization is to determine the data source. In the present study, the data source (i.e., manifestation of cultural discourses) is the quantified appearance of the cultural discourses within the 30 e-lit works. Therefore, to format the data source for Gephi, I converted the findings of the close reading into graphical data, and then created two different datasets using a spreadsheet tool.

The dataset number 1 quantifies the relation between the 30 e-lit works and the 10 cultural discourses, considering a directed connection and attributing a value of 1 when the discourse appears in the e-lit work. The dataset number 2 quantifies the co-occurrence of the discourses in the 30 e-lit works, attributing the value of 1 each time two discourses appear simultaneously in an e-lit work (value 0 if they don’t) and summing values for all the works. I then imported both datasets (.csv source files) to Gephi (version 0.9.2) and applied the force-directed layout algorithm, Force Atlas 2 to get an overview of the network structure54. Lastly, two network graphs were created: 1. Latin American e-lit works and cultural discourses and 2. Latin American cultural discourses’ cooccurrence.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Latin American e-lit works and cultural discourses network graph

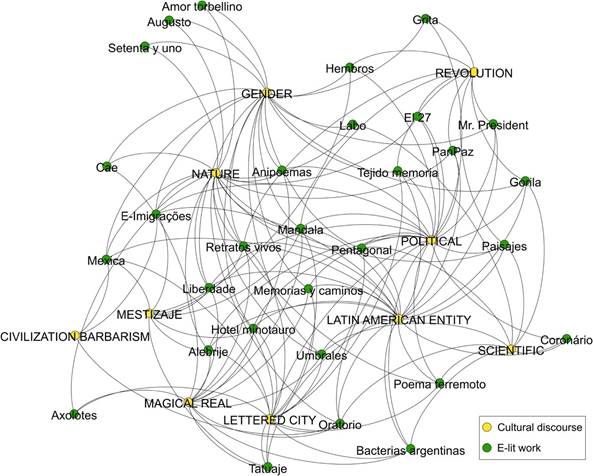

The overall structure of the first graph showed the connectivity between 30 Latin American e-lit works (source) and 10 cultural discourses (target) (Figure 1). There is a total of 40 nodes and 141 edges. The nodes are labelled by the 30 e-lit works (Figure 1 - green) and the 10 cultural discourses (Figure 1 - yellow), respectively. A default curved display was used as the connection is directed. In the directed graph, nodes with the highest degree have 21 edges (e.g., Latin American entity) and nodes with the lowest degree have 2 edges (e.g., Amor torbellino).

e-lit works and 10 cultural discourses. Source: Own work.

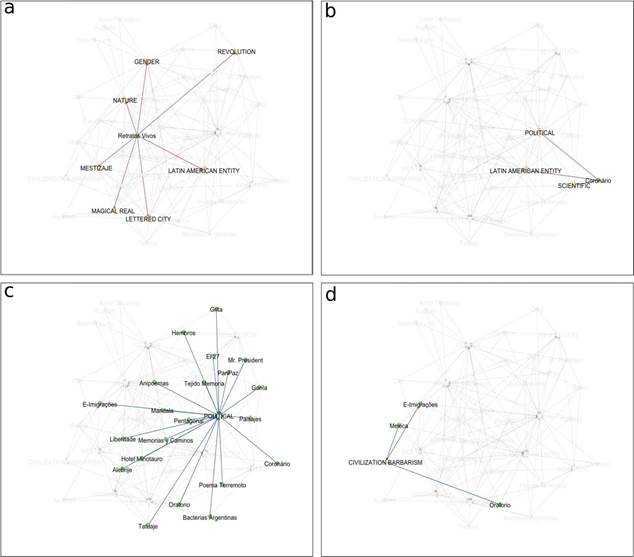

In terms of e-lit works, there are nodes that are both centrally positioned within the network and highly connected such as Retratos vivos (López, 2015) (Colombia)55 with 7 edges (Figure 2a); and nodes in the fringe of the network with just a few edges like Coronário (Beiguelman, 2020) (Brasil)56 with only 3 edges (Figure 2b). In terms of cultural discourses, there are highly connected nodes such as political with 21 edges (Figure 2c) and other nodes with fewer connections like civilization vs. barbarism with only 3 edges (Figure 2d).

To explore the importance of each connection, I measured the in-degree centrality of the target node (discourses) to examine the number of e-lit works connected to each discourse and the out-degree centrality of the source node (e-lit works) to examine the number of discourses to which each e-lit work was connected.

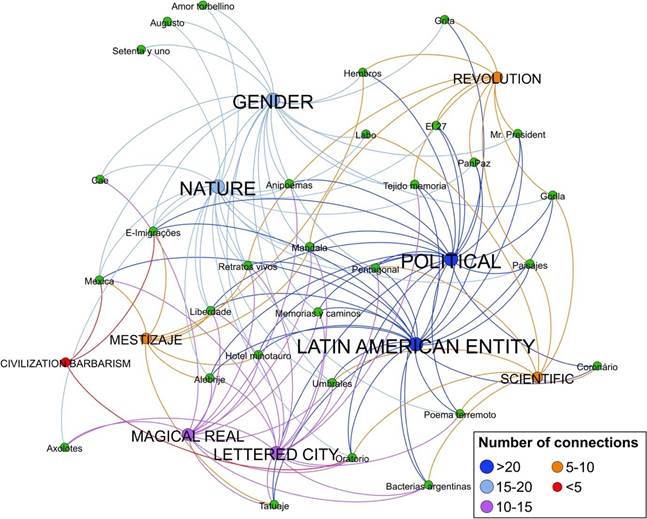

4.1.1. In-degree centrality graph

The in-degree centrality graph showed in Figure 3 enables to answer the following question: What are the primary, secondary, and tertiary discourses in 30 Latin American e-lit works? The node and label size are ranked by in-degree with the biggest size indicating the highest number of connections. The thickness of the edges is not weighted (value of 1) which means they are all considered equal. A default curved display was used as the connection is directed. The different colors refer to the number of connecting e-lit works (see color bar in Figure 3).

of 10 cultural discourses. Source: Own work.

In the directed graph, there are two pairs of densely connected nodes sharing the same number of in-degree centrality, respectively: a) Latin American entity and political with 21 edges (Figure 3 - dark blue) and b) nature and gender with 20 edges (Figure 3 - light blue). This illustrates that around 60% of the graph is occupied by these four primary discourses. The secondary group is represented by the two neighboring discourses lettered city and magical real with 15 and 13 edges, respectively (Figure 3 - purple). The four discourses left (revolution, scientific, mestizaje and civilization vs. barbarism) have less than 11 edges each and can be classified as a tertiary group (Figure 3- orange and red).

The node proximity of the secondary discourses, lettered city and magical real shows the strength of their connection and potential co-occurrence; the fact that both nodes are located in the lower right part of the graph is due to their association to e-lit works positioned in the periphery such as Olhar axolotes (Pinto, 2004) (Brasil), Tatuaje (Rodolfo JM et al., 2014) (Mexico) and Bacterias argentinas (Ortiz, 2004) (Colombia) (Figure 3 - purple). By contrast, the tertiary discourses (revolution, scientific, mestizaje and civilization vs. barbarism) are represented by nodes completely scattered in the periphery of the graph (Figure 3 - orange and red), which indicates their low presence in the e-lit works. For instance, the tertiary discourse civilization vs. barbarism is an unusual node because it is connected to only 3 e-lit works in the whole network: Oratorio (Vallias, 2003) (Brasil), Mexica (Pérez y Pérez, 2017) (Mexico) and E-Imigrações (dos Santos, et al., 2019) (Brasil). However, the peculiarity here is that these nodes are densely connected and, as we shall see later, have a high presence of multi-discourse, which makes them rather influential in the graph. Therefore, the appearance of tertiary discourses in multi-discourse works increases the probability that they would appear in co-occurrence with primary discourses.

Moreover, revolution is another tertiary discourse that has a noteworthy behavior because a family of 10 e-lit works seems to be attracted by this node. This attraction produces a noticeable presence of gathering nodes in the upper right side of the graph (Figure 3 - orange). Among the works associated to this node there are: Grita (Aburto, 2004) (Peru), Hembros (Prado, 2004) (Chile), El 27 (Tisselli, 2014) (Mexico), PanPaz imagine (Padín & Venera, 2001) (Uruguay-Brasil) and Mr. President (Bonino, 1999) (Peru), to name but a few. This result is quite revealing because the identification of gathering nodes associated to specific discourses, in this case revolution, would be useful to conduct close reading research using smaller datasets.

Lastly, there are certain nodes within the structure of the network that act as bridges between otherwise disconnected groups. For example, the unexpected densely connected discourse nodes gender and nature with 20 edges each (Figure 3 - light blue), function as solid bridges to the three peripheral e-lit works positioned in the upper left fringe of the graph, Amor Torbellino (Aranda, 2001) (Chile), Augusto (Calcanhotto, 2011) (Brasil) and Setenta y uno (Cociña, 2004) (Chile). It is important to mention that this particular group would be completely separated from the network if it weren’t for these two strong connections (gender and nature). This shows that identifying bridges in a larger network would certainly give a better idea of the influence that densely connected nodes (primary discourses) have in keeping small groups of e-lit works together.

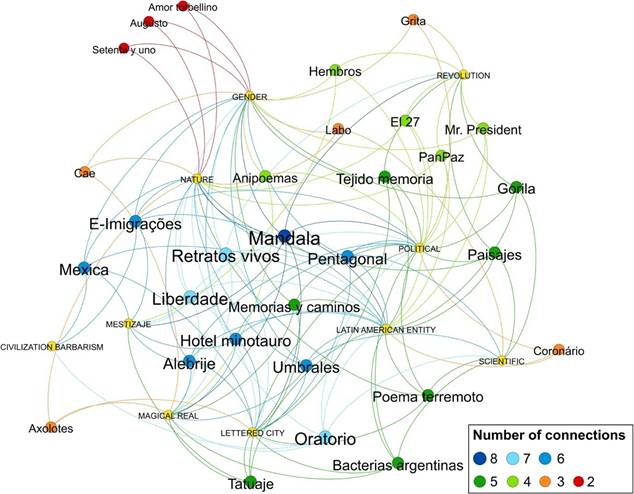

4.1.2. Out-degree centrality graph

The out-degree centrality graph illustrated in Figure 4 enables to answer the following questions: What is the degree of multi-discourse in 30 Latin American e-lit works? Can we find families of e-lit works sharing the same discourses? In the graph, the node and label size are ranked by outdegree, with the biggest size indicating the highest number of connections. The thickness of the edges is not weighted (value of 1) which means they are all considered equal. A default curved display was used as the connection is directed. The different colors refer to the number of connecting discourses (see color bar in Figure 4).

of 30 Latin American e-lit works. Source: Own work.

The results suggest that in 30 Latin American e-lit works there are not nodes connected to a single discourse as the number of edges ranges between 2 and 8 with an average of 5. Those e-lit works with 2 to 3 edges are all found in the fringe of the graph showing different patterns. The group of 3 peripheral nodes positioned in the upper left of the graph that was previously mentioned in the in-degree centrality graph (Figure 3 - light blue) appears here as family (Figure 4 - red), which highlights the importance of identifying gathering nodes associated to specific discourses, in this case: gender and nature.

Likewise, there is a group of 5 scattered nodes in different parts of the out-degree centrality graph with an average of 3 edges per e-lit work (Figure 4 - orange). The distance and spatiality between the nodes indicate that even though all the nodes have the same number of edges, they do not necessarily share the same discourses, as it is seen in Grita (Aburto, 2004) (Peru) and Olhar axolotes (Pinto, 2004) (Brasil), where not a single discourse is alike.

Furthermore, the highest multi-discourse group, consisting of nodes with more than 5 edges, is positioned towards the center of the graph (Figure 4 - dark and light blue). In this particular group, the highest out-degree node in the whole graph is represented by Mandala (Jaramillo, 2017) (Colombia) with 8 connections in total, followed by Liberdade (Chico Marihno et al., 2013) (Brasil) with 7, and Pentagonal (Labbé, 2001) (Chile) with 6, to mention but a few examples. It can be observed from the network visualizations that these e-lit works tend to be neighboring nodes instead of being dispersed in the periphery. In other words, the fact that they are all located towards the center of the graph indicates that the works are mainly connected to primary and secondary discourses of the network.

Therefore, these results support the idea of multi-discourse e-lit works displaying different behaviors. That is, such works can reveal new strong associations between primary discourses and tertiary discourses, as observed in the following examples: gender and revolution in Retratos vivos (López, 2015) (Colombia); gender and mestizaje in Hotel Minotauro (Chiappe, 2015) (Peru- Venezuela); gender and scientific in Labo (Villeda, 2010) (Mexico); and lastly, gender and civilization vs. barbarism in E-Imigrações (dos Santos, et al., 2019) (Brasil).

The emergence of theme centred communities in the graph can be useful for scholars in search of works with these specific characteristics. To give an example, the study of “gender patterns behavior” within the 30 e-lit works can be approached by comparing how many of the works associated to gender discourse in the in-degree centrality graph (Figure 3 - light blue) appear as a family or are part of the same family in the out-degree centrality graph (Figure 4). Certainly, a comparison of both results would reveal interesting associations between the e-lit works and the cultural discourses that couldn’t be seen by only applying close reading.

Another important aspect of multi-discourse e-lit works, such as Oratorio (Vallias, 2003) (Brasil), is the fact that they are usually connected to low frequency tertiary discourses like civilization vs. barbarism. This suggests that in the graph there are e-lit works with high presence of multidiscourse that are connected to tertiary discourses; and vice versa, low presence multi-discourse e- lit works like Augusto (Calcanhotto, 2011) (Brasil), that are connected to primary discourses such as nature and gender. Overall, this means that multi-discourse features are not necessarily linked to strong co-occurrences between discourses. To put it differently, an e-lit work can have multiple discourses but few co-occurrences.

Finally, two groups with an average of 4 to 5 edges that occupy mostly the upper right part of the graph were identified (Figure 4 - dark and light green). The first group contains the largest number of works with the same number of discourses in the graph, that is, 7 e-lit works with 5 discourses each (Figure 4 – dark green). Besides, these two groups show a tendency towards gender, revolution and political discourses, which is clearly reinforced by the appearance of a new family of works including: Mr. President (Bonino, 1999) (Peru), Tejido de memoria (Zerbarini, 2003) (Argentina), Hembros (Prado, 2004) (Chile), Gorila esquizo (Läufer, 2017) (Argentina), among others (Figure 4 - dark and light green). Interestingly, this finding also accords with the observations presented before (Figure 3 - orange), which showed that the identification of gathering nodes associated to specific discourses can be beneficial for comparative node behavior between in-degree and out-degree graphs.

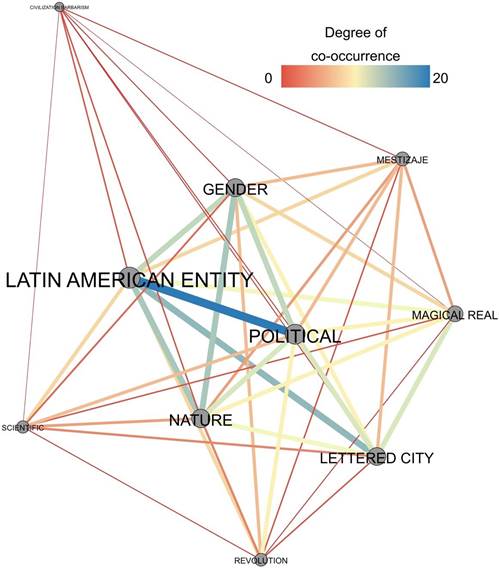

4.2. Latin American cultural discourses co-occurrence network graph

The undirected graph illustrated in figure 5 enables to answer the following question: How strong is the co-occurrence of cultural discourses in 30 Latin American e-lit works? How does discourse co-occurrence exhibit different patterns in the e-lit works? The overall structure of the network shows the connectivity between 10 cultural discourses. There is a total of 10 nodes and 43 edges. The node and label size are ranked by weighted degree. The thickness and the color of the edges are weighted by degree of co-occurrence (e.g., how many times two discourses simultaneously appear in the 30 e-lit works) (see color bar Figure 5). A default straight display was used as the connection is undirected.

of 10 cultural discourses in 30 Latin American e-lit works. Source: Own work.

In the undirected graph, the highest co-occurrence is observed between the two primary discourses Latin American entity and political with a total of 18 works (Figure 5 - light blue). There is also a strong co-occurrence between Latin American entity and the following discourses: lettered city (14 works), nature (13 works), and gender (12 works); as well as political and the following discourses: gender (12 works), lettered city (11 works), and nature (11 works) (Figure 5 - light green). This is related to the fact that Latin American entity and political, nature and gender are primary discourses with the highest degree of appearance in the works with a total of 21 works (70%) and 20 works (66%), respectively, and therefore have many connections (Figure 3 - dark and light blue).

The strong presence of the secondary discourse lettered city and its co-occurrence with the four primary discourses must be highlighted. Its strength indicates that lettered city stands as a transition discourse between high and low edge connections (Figure 5 - light green). Likewise, the cooccurrence between nature and gender, and magical real and lettered city are significantly high with a total of 13 and 11 e-lit works, respectively. The node proximity of the secondary discourses, lettered city and magical real previously shown in the in-degree network graph (Figure 3 -purple) is confirmed here by the strength of their co-occurrence. Lastly, the fact that revolution, scientific and mestizaje are located in the fringe of the graph explains their low co-occurrence with other discourses but not necessarily means they need to be associated to low multi-discourse e-lit works.

It seems that co-occurrence patterns between primary discourses are not strictly conditioned or associated to highly multi-discourse works. This means that there are e-lit works with low level of multi-discourse that are connected to primary discourses, like Setenta y uno (Cociña, 2004) (Chile), whose single and highest co-occurrence is between the primary discourses nature and gender; and vice versa, e-lit works with high level of multi-discourse that are connected to tertiary discourses - making them influential nodes- like the high multi-discourse work, Oratorio (Vallias, 2003) (Brasil), that is also host to the rarest co-occurrence pattern in the network, the unique coupling: civilization vs. barbarism and scientific.

As expected, the tertiary discourse civilization vs. barbarism is the farthest node in the graph, this explains its low discourse co-occurrence with the rest of the network. Even though, it is connected to eight discourses, its co-occurrence is only represented by 1 e-lit work per edge (Figure 5- red), which consequently reduces its presence in the graph. Lastly, it must be emphasized that while there are co-occurrences that never occur in the 30 e-lit works, such as civilization vs. barbarism and revolution; and scientific and mestizaje, this does not mean that these couplings would not be present in a larger corpus.

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. Cultural discourse variations and new co-occurrences in Latin American e-lit works

The main objective of the study was to identify how cultural discourses are related in 30 Latin American e-lit works published from 1995 to 2020 by applying distant reading methodologies. Contrary to expectations, the results showed that Latin American entity and political discourses are not always dominant. The graphs indicate otherwise and suggest that important variations occur not only when new discourses come into play, such as nature and gender -becoming primary discourses themselves-; but also, when new significant co-occurrences are formed between primary and tertiary discourses (e.g., political and revolution or gender and mestizaje). It might be the case that these variations suggest that discourses not only “adapt, transmute and perpetuate themselves in online cultural productions” (Taylor & Pitman, 2013, p. 1) but also emerge and are born out of new circumstances and contexts creating new and strong associations or patterns.

The purpose of testing these methodologies was to open the following discussion: What drives cultural discourse diversity and frequency in Latin American e-lit works? What could be the criteria to influence these variations? (time, authorship, genre, distribution, geographical/code migration). That is, if discourses are either directly associated to the evolution of literary genres and technological apparatus in each individual context, or if it is principally the impact of economic, political, and socio-cultural factors (inside and outside Latin America) what triggers these variations, or perhaps a combination of both. The fact that e-lit is part of a versatile and global digital culture means that its production will always be influenced by these external factors, which will inevitably have an impact on the cultural discourse creativity of the e-lit works.

Thus, if e-lit is considered as a system of communication practices where words, deeds, values, beliefs, symbols, tools, objects, times, and places intertwine (Gee, 2014), I argue that the analysis of networks of cultural discourses can provide a panorama not only of the stylistic devices of the authors but also of the cross-linguistic and cross-cultural variations that take place within the e-lit works. For instance, the repeated use of certain discourses in specific countries, the comparison of discourse co-occurrence patterns in others, the use of bilingual discourse in the e-lit works (e.g., Portuguese-Spanish, or Portuguese-Spanish and Indigenous languages), or the emergence of new discourse co-occurrences in response to economic, political, and socio-cultural factors. A way to test these hypotheses to better understand the evolution of cultural discourse in Latin American e-lit, would be to create network graphs for different periods of time (e.g., having one network graph per decade), e-lit genres, and e-lit generations (Flores, 2017; Hayles, 2008) to further study what drives any changes or variations.

5.2. Benefits of network graphs for revealing patterns, connections, and families

The application of digital humanities methods such as distant reading to explore e-lit materials has proven to be useful when it comes to identifying families of e-lit works with similar discursive characteristics. Therefore, the information shown in the graphs can be of interest to both scholars and creators. For scholars, extracting information from the graphs can be helpful when performing separate close reading and literary analyses in certain e-lit works. To give an example, the graphs can be a starting point to study individual aspects of Latin American e-lit, such as revolutionary allusions, literary representation of cities, political movements, gender patterns, magical imagery, or eco-critical manifestations, to name but a few. The visualizations can be seen as a first step to identify e-lit work families that show these specific features, which could facilitate the further examination of individual datasets.

Moreover, for artists, the graphs can provide a quick view of what other individuals are currently creating or have been creating in the past 25 years in the Latin American e-lit scene. The visualizations are a tool to zoom in and zoom out into the information of the works. On the one hand, they are a way to see “from the distance” the diversity and frequency of cultural discourses in 30 e-lit works, but on the other hand, they are a way to take “a closer look” at the intersections and cooccurrences between the discourses. Thus, the identification of families of e-lit works, cultural discourse variations, and new discourse co-occurrences in Latin American e-lit have significant implications for the understanding of the styles of communication of the artists, the practices of communication of the works, and lastly, the connections and variations that exist within the digital literary production in Latin America.

5.3. Using data visualization techniques to study future e-lit anthologies, collections, and databases

The present study has demonstrated that the application of distant reading methodologies can be useful to explore e-lit materials particularly when the creation of collections, anthologies and databases is at the core of multiple international e-lit research projects (The Consortium on Electronic Literature (CELL), 2015; The Electronic Literature Collections Vols. 1-3., 2006; The ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Base, 2010). Certainly, a deeper knowledge of Latin America’s e-lit production in terms of cultural discourse diversity would be possible by testing the present methodology in a larger database. For this reason, I consider that this work can be extended to the recently published Anthology of Latin American Electronic Literature, Antología Lit(e)Lat Vol. 1 (Flores et al., 2020)55 and the two forthcoming Latin American e-lit database research projects: Cartografía de la Literatura Digital Latinoamericana [Cartography of Latin American Digital Literature] (Gainza & Zuñiga, 2021)56 and Repositório da Literatura Digital Brasileira [Repository of Brasilian Digital Literature] (Rocha, 2021)57. For all of these initiatives are an important contribution to the Latin American and international e-lit communities not only because they will help to visualize works, countries, languages, genres, and authors -as well as underline the importance and challenge of storing, archiving and preserving e-lit works-; but also because they present a perfect ground to test new hypotheses and research questions on the evolution of cultural discourses, genres, or technological apparatus within different regions and time periods.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The aim of this paper was to analyze networks of cultural discourses in a corpus of 30 Latin American e-lit works by applying distant reading methodologies. To conduct the research, three network graphs were created using Gephi, an open-source software for the exploration and analysis of network visualizations. The in-degree centrality graph provided a way to visualize the frequency of each discourse as well as to reveal how primary discourses create strong connections and potential co-occurrences with tertiary discourses. The out-degree centrality graph provided a way to evaluate the degree of multi-discourse of each e-lit work which can be used as a criterion to define families. The co-occurrence network graph revealed that the degree of cultural discourse cooccurrence is not conditioned or associated to multi-discourse features. Overall, the results show the appearance of unexpected discourse variations and new co-occurrence patterns, the benefits of network graphs for revealing e-lit works’ families, and the potential use of data visualization techniques to study e-lit databases.

The present study is a first attempt to prove that the interdisciplinarity between Electronic Literature and Digital Humanities research methods can be beneficial for both research communities. Data visualization techniques have demonstrated to be a reliable and efficient methodological tool that can be applied to examine further electronic literature materials. The work presented here is only one example of the potential interdisciplinarity between both fields considering the plethora of data visualization techniques and the diversity of e-lit research lines. At a larger scope, digital humanities research methods are a promising approach to conduct multiple studies in different international e-lit databases.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Aburto, J. (2004). Grita. http://entalpia.pe/

Antología de poesía electrónica. (2018). Centro de Cultura Digital México. http://editorial.centroculturadigital.mx/pieza/antologia-de-poesia-electronica

Antologías de cuento digital Itaú. (2011). Itaú Fundación. https://www.antologiasitau.org/

Aranda, I. (2001). Amor Torbellino. http://www.escaner.cl/netart/_yto-digital.html

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An Open Source Software for Eexploring and Manipulating Networks. 3. https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/09/paper/ view/154

Beiguelman, G. (2020). Coronário. https://coronario.ims.com.br/en/about Benech, L. (2015). Paisajes. https://laurabenech.net/proyectos/

Boluk, S., Flores, L., Garbe, J., & Salter, A. (Eds.). (2016). The Electronic Literature Collection, Volume Three. Electronic Literature Organization. http://collection.eliterature.org/3

Bonato, A., D’Angelo, D. R., Elenberg, E. R., Gleich, D. F., & Hou, Y. (2016). Mining and Modeling Character Networks. In A. Bonato, F. C. Graham, & P. Prałat (Eds.), Algorithms and Models for the Web Graph (pp. 100-114). Springer International Publishing. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49787-7_9

Bonino, A. (1999). Mr. President. https://vimeo.com/20323466

Borràs, L., Memmott, T., Ralay, R., & Stefans, B. (Eds.). (2011). The Electronic Literature Collection, Volume Two. Electronic Literature Organization. http://collection.eliterature.org/2

Bouchardon, S. (2014). Figures of Gestural Manipulation in Digital Fictions. In A. Bell, A. Ensslin, & H. Rustad (Eds.), Analyzing Digital Fiction (pp. 159-175). Routledge.

Brooke, C. G. (2009). Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media. Hampton Press.

Calcanhotto, A. (2011). Augusto. https://atlasldigital.wordpress.com/

Carbaugh, D. (2007). Cultural Discourse Analysis: Communication Practices and Cultural Encounters. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 36(3), 167-182. https:// doi.org/10.1080/17475750701737090

Chiappe, D. (2015). Hotel Minotauro. https://www.domenicochiappe.com/hotel-minotauro/ Cociña, C. (2004). Setenta y uno. http://www.esteticasdigitales.cl/poesia-cero/

De la Torre, Y., Gómez, R., Nepote, M., & Baram, N. (2014). Umbrales. http://www.umbrales.mx dos Santos, A. L., Duarte, R., & Rutes, V. (2019). E-Imigrações. http://nupill.ufsc.br/producao/e-

Eder, M. (2017). Visualization in stylometry: Cluster analysis using networks. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 32(1), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqv061

EMargin. (2015). https://emargin.bcu.ac.uk/

Eyman, D. (2015). Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice. University of Michigan Press.

Flores, L. (2017). La literatura electrónica latinoamericana, caribeña y global: Generaciones, fases y tradiciones. Artelogie. Recherche sur les arts, le patrimoine et la littérature de l’Amérique latine, 11. https://doi.org/10.4000/artelogie.1590

Flores, L., Kozak, C., & Mata, R. (Eds.). (2020). Antología Lit(e)Lat Volumen 1. Red de Literatura Electrónica Latinoamericana. Red de Literatura Electrónica Latinoamericana. htp://antologia.litelat.net/

Fontén, G. (2010). Poema Terremoto. http://www.esteticasdigitales.cl/poema-del-terremoto/

Gainza, C. (2016). Cultura Digital Chile Project. http://culturadigitalchile.cl

Gainza, C., & Zuñiga, C. (Eds.). (2021). Cartografía de la Literatura Digital Latinoamericana: Visualización, archivo y preservación de obras literarias digitales. Universidad Diego Portales, Facultad de Comunicación y Letras. FONDECYT Chile. https://www.cartografiadigital.cl

Gandolfi, E. (2018). Enjoying Death Among Gamers, Viewers, And Users: A Network Visualization of Dark Souls 3’s Trends on Twitch.Tv And Steam Platforms. Information Visualization, 17(3), 218-238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473871617717075

Gattass, L. (2012). Brasilian Electronic Literature Collection. ELMCIP. https://elmcip.net/research- collection/brazilian-electronic-literature-collection

Gee, J. P. (2014). An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method (4th ed.). Routledge. Gil-Vrolijk, C., & Giraldo, C. (2004). El alebrije. http://www.elalebrije.org/

Goicoechea, M., & Sánchez, L. (2014). CIBERIA project. http://www.ciberiaproject.com/

Hayles, K. (2008). Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. University of Notre Dame Press.

Hayles, K., Montfort, N., Rettberg, S., & Strickland, S. (Eds.). (2006). The Electronic Literature Collection, Volume One. Electronic Literature Organization. http://collection.eliterature.org/1

Jänicke, S., Franzini, G., Cheema, M. F., & Scheuermann, G. (2015). On close and distant reading in digital humanities: A survey and future challenges. Eurographics Conference on Visualization (EuroVis)-STARs. The Eurographics Association. htp://dx.doi.org/10.2312/eurovisstar.20151113

Jaramillo, A. (2017). Mandala. https://www.novelamandala.com/

JM, R., Aranda, L., & Gordillo, G. (2014). Tatuaje. htps://editorial.centroculturadigital.mx/pieza/tatuaje

Jockers, M. L. (2013). Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. University of Illinois Press. Labatut, V., & Bost, X. (2019). Extraction and Analysis of Fictional Character Networks: A Survey.

ACM Computing Surveys, 52(5), 89:1-89:40. https://doi.org/10.1145/3344548 Labbé, C. (2001). Pentagonal: Incluidos tú y yo. http://www.esteticasdigitales.cl/pentagonal/ Läufer, M. (2017). Gorila Esquizo. http://www.miltonlaufer.com.ar/gorila/

López, C. (2015). Retratos vivos de mamá. https://www.retratosvivosdemama.co/

Marinho, F., dos Santos, A. L., Andrade-García, A., & Barbosa, R. (2013). Liberdade. https:// www.ciclope.com.br/liberdade-english/#conteudo

Meza, N. (2019). Voces y figuras: Hacia una retórica digital de las obras de literatura electrónica latinoamericana. Texto Digital, 15(1), 39-65. https://doi.org/10.5007/1807- 9288.2019v15n1p39

Moretti, F. (2005). Graphs, maps, trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History. Verso. Ortiz, S. (2004). Bacterias Argentinas. http://moebio.com/santiago/bacterias/ Padín, C., & Venera, A. (2001). PanPaz_imagine. https://pan-paz.crosses.net

Pawlicka, U. A. (2016). Visualizing Electronic Literature Collections. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2902

Pérez y Pérez, R. (2017). Mexica: 20 Years 20 Stories [20 años 20 historias]. http://www.rafaelperezyperez.com/profile/publications/

Pinto, R. C. (2004). Olhar Axolotes. htps://elo-repository.org/museum-of-the-essential/arteonline4/definitionenglish.htm Pose Rivero, L. (2018). Cae. http://salta.atwebpages.com/#cae

Prado, E. (2004). Hembros: Asedios de lo post humano. htp://hembros-eugeniaprado.blogspot.com/

Rettberg, J. W. (2014). Visualising Networks of Electronic Literature: Dissertations and the Creative

Works They Cite. Electronic Book Review. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/visualising-networks-of-electronic-literature-dissertations-and-the-creative-works-they-cite/

Rettberg, S. (2014). An Emerging Canon? A Preliminary Analysis of All References to Creative Works in Critical Writing Documented in the ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Base. Electronic Book Review. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/an-emerging-canon-a- preliminary-analysis-of-all-references-to-creative-works-in-critical-writing-documented-in- the-elmcip-electronic-literature-knowledge-base/

Rettberg, S. (2019). Electronic Literature. Polity Press.

Rocha, R. (2019). Atlas de Literatura Digital Brasileira. http://www.atlasldigital.ufscar.br

Rocha, R. (2021). Repositório da Literatura Digital Brasileira. Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brasil. Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). https:// museu2.tainacan.org

Rodríguez, J. A. (2016). Memorias y Caminos. http://www.memoriasycaminos.com

Saemmer, A. (2015). Rhétorique du texte numérique: Figures de la lecture, anticipations de pratiques. Université de Lyon Presses de l’Enssib.

Seiça, Á. (2016). Digital Poetry and Critical Discourse: A Network of Self-References? MATLIT: Materialidades Da Literatura, 4(1), 95-123. https://doi.org/10.14195/2182-8830_4-1_6

Taylor, C., & Pitman, T. (2013). Latin American Identity in Online Cultural Production. Routledge.

The Consortium on Electronic Literature (CELL). (2015). https://cellproject.net

The Electronic Literature Collections Vols. 1-3. (2006). https://collection.eliterature.org

The ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Base. (2010). http://elmcip.net/knowledgebase Tisselli, E. (2014). El 27. http://motorhueso.net/27/

Uribe, A. M. (1997, 2003). Anipoems. http://www.vispo.com/uribe/index.html Vallias, A. (2003). Oratorio. https://www.andrevallias.com/oratorio/

Villeda, K. (2009). LABO/Laboratorio de ciberpoesía. http://www.poetronica.net/LABO/index.html

Zalbidea, M. (2014). Spanish Language Electronic Literature. ELMCIP. https://elmcip.net/research-collection/spanish-language-electronic-literature

Zerbarini, M. (2003). Tejido de memoria. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4B4- D7jIKI&feature=youtu.be

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8382-1768

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8382-1768